València, 4 de març de 2014

The University participates in the discovery of the ancient oral microbiome trapped in dental plaque.

- Nature Genetics publishes a research report that has developed a new methodology capable to describe, for the first time, the dental flora in an archaeological population and, therefore, open the door to apply this technique to facilitate the understanding of human evolutionary history.

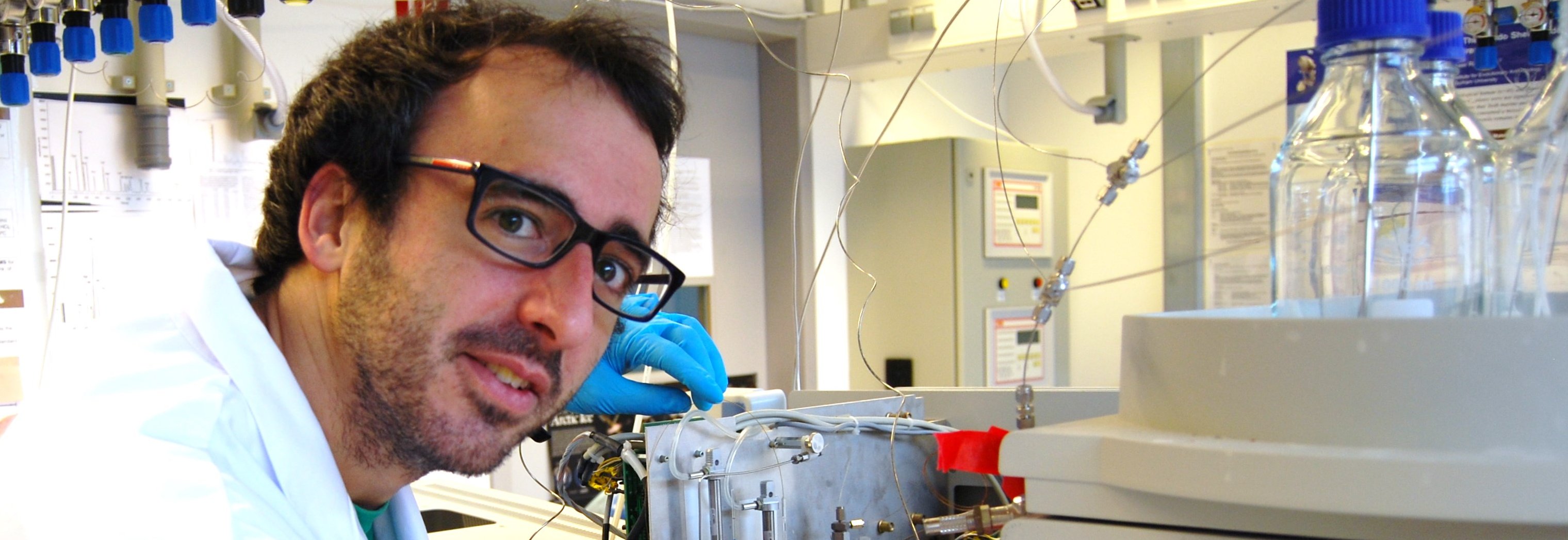

The University of Valencia has participated in the development of a new methodology that has made it possible to describe in detail the microbial flora in the oral cavity in an archaeological population. This opens the door to apply this technique to facilitate the understanding of human evolutionary history. Postdoctoral researcher Domingo Carlos Salazar García, who earned his doctorate from the University of Valencia, has been part of the international team that has discovered the ancient oral microbiome trapped in the teeth of thousand-year old skeletons from the German medieval site of Dalheim. The key finding is the mineralized plaque in dental calculus, which retain bacteria and microscopic food particles and constitutes a type of receptacle for microbiomes. The results of this pioneering work on the ecology of the oral microbiome and its role have been published online in Nature Genetics, and 32 researchers from twenty institutions in seven countries have participated in it.

Domingo Carlos Salazar, currently a researcher at Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology (Leipzig, Germany) says that, until now, it was known that microscopic particles of food were preserved in dental calculus, but "we were unaware of their excellent degree of preservation." Salazar García argues that dental calculus "are proving to be an important window into the past, because they can provide valuable information on the health and food of our ancestors, as well as on their lifestyle. Never before have we been able to obtain as much data from such a small sample."

INVARIABLE BACTERIA RESPONSIBLE FOR PERIODONTAL DISEASE

Researchers have found that the oral cavity of ancient humans preserves numerous opportunistic pathogens, and that periodontal disease is caused by the same bacteria as in the past, despite the great changes in human diet and hygiene. The international team of scientists have also discovered that the ancient human oral microbiome already had the basic genetic mechanisms for resistance to antibiotics (eighth centuries before the invention of the first therapeutic antibiotics in the 1940s). In addition to information about health, researchers have analyzed the DNA and identified components of the diet of ancient populations, such as the species of plants (wheat, cabbage) and animals (lamb, pork) that they ate.

The project, led by Christina Warinner, from the University of Zurich and the University of Oklahoma, reveals that, unlike bones, which quickly lose much of their molecular information when buried, dental calculus enters the soil in a more stable state that helps preserve biomolecules. For this reason, the analysis of ancient DNA was not hindered by the burial of the remains.

This group of scientists has applied, for the first time, massive DNA sequencing techniques to calculus, along with other proteomics capable of identifying the proteins preserved in them. As a consequence, it has been possible to reconstruct the genome of periodontal pathogens, while achieving the first evidence of the diet of ancient humans through biomolecules. This study not only helps to improve the understanding of the evolution of the human oral microbiome, but also of the origins of periodontal disease, which causes changes in the dentition and is characterized by chronic inflammation resulting in the loss of teeth and bone. Today, more than 10% of the world population suffers from severe periodontal disease, which is linked to other cardiovascular and pulmonary diseases, or to type II diabetes.

Salazar García points out that in the world of archeology "dental calculus has not been given the importance it deserves. Therefore, it will be necessary to prevent damage during excavations and subsequent processing of the material to a part of the archaeological record that can provide even more information than the teeth themselves."

Domingo Carlos Salazar García was born in Valencia and is a postdoctoral researcher at the Max-Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, but he still maintains close ties with the University of Valencia. He works in biomolecular archaeology in order to reconstruct the type of food eaten by our ancestors and their state of health, as well as their interaction with the environment. He graduated in Medicine and in History from the University of Valencia, obtaining a extraordinary award, earned an European doctorate in Prehistory and Archaeology from the University of Valencia, with an excellent cum laude, and a Master's Degree in Forensic Medicine from the ADEIT-University of Valencia Foundation. Salazar García has published more than 40 articles in international and national science and popular science journals and books. He has been a guest speaker at institutions such as National Geographic Society and has participated in over 40 national and international conferences.

More information:

http://www.nature.com/ng/journal/vaop/ncurrent/full/ng.2906.html

PIE DE FOTO: Mineralized dental plaque on the teeth of a middle-aged man from the medieval site of Dalheim, DC 1100. Photo: Christina Warinner.”