The geostrategic situation of the city of Valencia and the unfavourable course of the war for the republican side made the city a preferred destination for the evacuated civilian population and for numerous contingents of wounded and ill militias and military. Faced with this situation, the successive Valencian authorities undertook a profound readjustment of the city’s hospital system, which materialised in the ad hoc placement of at least twenty centres located inside and outside the Traffic rounds. The pre-existing hospitals also underwent a marked reorganisation. Thus, the Provincial Hospital, the Provincial Mental Hospital, the Sanatorium of Porta-Coeli and the Hospital of the Malva-rosa had to increase their hospitalisation capacity, which caused the overcrowding of patients and the decline of the care quality. The Red Cross Hospital School, whose beginnings go back to 1920, also had to face the contingencies of the fight: the accumulation of those wounded by firearm, the mobilisation of medical personnel, the closing of the nursing school, the placement of emergency health posts, the pressure of the revolutionary health authorities, etc.

At the end of the month of July 1936, the worrying news that, coming from Spain, reached the Red Cross central offices, in Geneva, on the execution of prisoners and wounded, alarmed the leaders of this humanitarian organisation. Max Huber – then president of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) – decided that the Swiss doctor Marcel Junod (1904-1961) arrived there to obtain first-hand information while visiting the two conflicting sides. As an ICRC general delegate in Spain, Junod effected a follow-up action on humanitarian activities in order to mitigate the impact of the war in the rearguard, such as prisoner exchanges, supervision of the prisoners conditions, distribution of clothing, food and medicines, assistance to victims of the bombings within the framework of the passive defence of the civil population, etc.

On May 28, 1937, a bombardment of the insurgents

broke the windows of the ICRC delegation in Valencia.

Source: Audiovisual Archives, ICRC (Geneva), VP-HIST-01.847-06..

On the other hand, the secretary of the Red Cross Central Committee of the republican zone – the libertarian doctor Juan Morata Cantón (1899-1994) – moved to Barcelona on September 3, 1936, to re-assemble the local committee, which he achieved after agreeing with the CNT on two names: Josep Martí Feced as medical director and Pere Estany as president of the Committee of Barcelona. With the same mission, Morata Cantón moved to Valencia, where he was received by the president of the local committee, Ricardo Muñoz Carbonero (1884-1944), doctor, specialised in radiology, among other things known because he had been councillor of the City Council of the Partido de Unificación Republicana Autonomista (PURA) controlled by Félix Azzati. Morata Cantón settled in the Salvador Seguí Street (current Count of Salvatierra Street), where the ICRC and the local committee of the Spanish Red Cross were headquartered. Swiss doctor Roland Marti (1909-1978), who left for Barcelona shortly after, was at the head of the delegation, formed by a group of 18 people.

Following the guidelines of Geneva, the mission of Morata Cantón in Valencia, as in Barcelona, was to adapt all the local Red Cross resources, both material and human, to the specific needs of an emerging civil war context. In this line, Morata Cantón got the anarchist Iron Column to respect the Red Cross (from now on RC) thanks to the CNT collaboration. But what resources did the RC have in the city of Valencia when the war broke out?

The 1957 flood destroyed all the documentation that RC’s activity had generated in the city until then (document books, invoices, staff lists, memoirs, etc.). Fortunately, a surgeon closely linked to the institution – José Antonio Borrás, who had been one of the founders of the hospital and who, at the end of the war, was its director – published a complete chronicle of the activities of the local committee from the late nineteenth century. This chronicle is the speech that he delivered on June 7, 1963 on the occasion of his admission to the Royal Academy of Medicine. Titled La Cruz Roja en Valencia, desde su fundación hasta nuestros días (‘The Red Cross in Valencia, from its foundation until today’), it is a mandatory reference for any subsequent historical approach. However, it is a historical source that needs to be tested based on its origin. In addition to the political context in which it was written, it is not possible to neglect that Borrás was an interested party, since he was still the director of the Hospital School when writing his speech.

The first RC actions in the city of Valencia date back to 1897, when the volunteers attended the victims of a strong flood of the Turia River. The following year, RC personnel attended the soldiers who returned injured or ill from Cuba and the Philippines. However, during this first stage the RC only had a horse-drawn ambulance and some offices located on the Arquebisbe Mayoral Street. It was not until 1906 that the RC had its own first sanitary infrastructure in the city: a polyclinic enabled in the square of Sant Bult and that, six years later, would move to the Governador Vell Street. In 1919, the first blood transfusion of the city took place during a surgical intervention practiced by doctors Manuel Candela and Rafael Vilar Sancho. The medical body was then integrated by twelve practitioners covering the main medical and surgical specialties.

The annual report of the local committee of 1912 ended up asking a question: “Why a Blood Hospital is not created that is named after the Red Cross?”. It was a widespread demand for RC surgeons, who considered that the polyclinic was not the ideal place to operate on patients, since the operated patients could not be hospitalised and had to be transferred to their homes. At the beginning of 1920, the first hospital of the RC was opened in the city of Valencia. It was settled in Antonio Suárez Street, just at the beginning of Port Avenue, taking advantage of the fact that Rafael Mollà, professor of Surgical Pathology, had gone to Madrid and had closed his clinic. The founding medical body of the hospital was made up of 22 professionals, among them José Antonio Borrás, mentioned above. Doctors were assisted by Capuchin tertiary nuns. One of them was a blood donor for a patient suffering from severe haemorrhage due to gastric ulcer in the room of Doctor Mario Ximénez del Rey. The work carried out by the hospital was eminently surgical (226 operations in 1920). The following year he welcomed the wounded and ill soldiers who arrived in Valencia from the war in North Africa.

During this time, the scientific and teaching vocation of the Valencia RC was already clear. In January 1922, the first issue of the Anales de la Policlínica de la Cruz Roja de Valencia magazine was printed, detailing the medical activity of the hospital and the polyclinic. Along the same lines, we must add the visit to the hospital centre of renowned surgeons of the time. Thus, on September 13, 1924, Dr. Manuel Corachan (1881-1942), a native of Chiva and head of the Surgery service of the Hospital de Sant Pau i la Santa Creu of Barcelona, involved three patients in the RC hospital. It should be noted that Valencian surgeons often visited the service that Corachan headed in Barcelona, where they met his disciples Josep Trueta and Jaume Pi i Figueras.

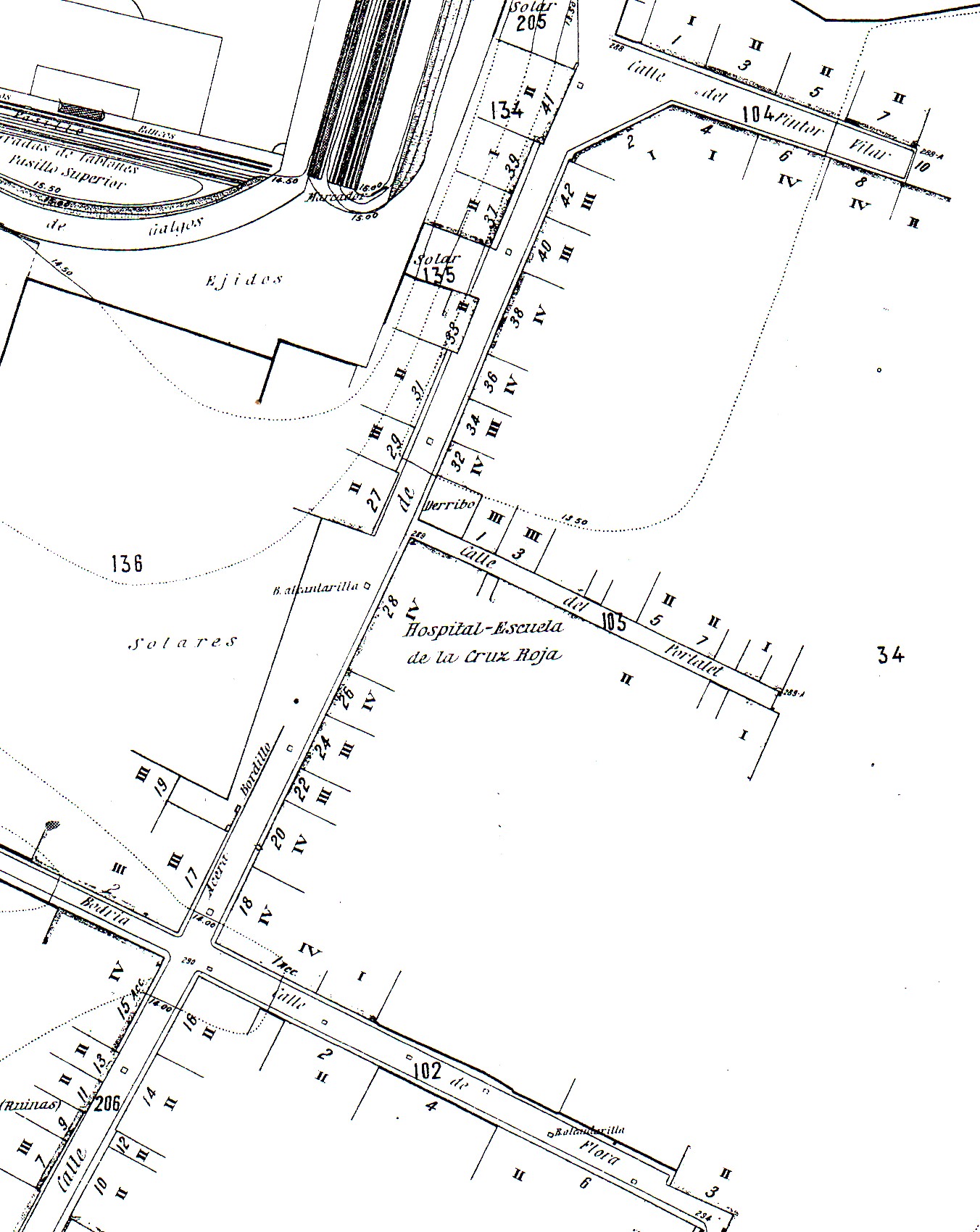

In the middle of 1926 the hospital was transferred to a new location in the city. It was installed in an old velvet factory – adapted for the new use – located on the corner of Portalet Street (now disappeared) with the number 26 of Alboraia Street. In addition, in 1930 a second polyclinic was established, annexed to the new hospital. The medical body of this new polyclinic was made up of 23 professionals, among them the pediatrician Mercedes Mestre Martí, the only woman, well-known because during the war she became undersecretary of Health with the minister Federica Montseny.

Situation of the Red Cross Hospital School in Valencia.

Note in the upper left part of the Vallejo football field,

where Llevant UE played between 1925 and 1968.

Source: Municipal Historical Archive, cadastral plan, quadrant 38, subquadrant III. Legend.

During the Republican stage new pavilions were built to widen the polyclinic annexed to the hospital, and a large number of medical instruments were acquired. No doubt, as a result of the intense surgical activity that was carried out there, in the middle of 1934, the direct blood transfusion, from person to person, began to be routinely performed. The transfusion team was formed by a doctor, a pharmacist, a practitioner and a group of donors from all the groups known at that time. In 1935 the hospital was reorganised and new services were added, such as ophthalmology, nutrition and urology. Disassembled of the surgery service, the latter was led by Víctor Mollà Fambuena (1901-1972), son of the aforementioned surgery professor. The new service underwent remarkable improvements that allowed the performance of cystoscope explorations and functional tests.

The RC was respected by the revolutionary committees of the city, and the doctors continued to do normal service, both at the polyclinic and in the hospital, attending to those wounded by a firearm in the city’s street shootings due to the political and social instability brought about by the military coup. For this reason, it was necessary to install in the same hospital an urgent health post, where four doctors were assigned. In addition to this post, since the summer of 1936, the RC had four more installed in Valencia: in the “Coliseum” theatre (Gran via de les Germanies Street corner with Castelló Street); in the disappeared Na Rovella Street; the anti-tuberculous dispensary on the port Avenue; and in the Salesians school, located on the Traffic path corner with Sagunt Street. It should be noted that these five RC health posts were integrated into a much larger network formed by a total of 26 posts, which were quickly placed throughout the city the last days of the same month of July 1936. The medical reports of the services provided by the Valencia Red Cross in the first days of war bring us closer to the violence that was experienced in the streets of Valencia during the first days after the military uprising. Thus, between July 20 and August 17, 1936, a total of 216 people were treated at the RC posts, most of them due to bruises, injuries, traumas, fractures and injuries caused by a firearm.

During the summer of 1936 the personnel of the RC Hospital was formed by 24 doctors trained in the main specialties. Given the political climate that prevailed in the city of Valencia, all RC doctors had to join political parties or leftist unions. As in previous times, none of them received remuneration. They were professionals who worked in the private sector and / or in different medical institutions of the city (Municipal Charity, Provincial Hospital, Municipal Health Service, professional mutual societies, etc.) and who, therefore, volunteered in this hospital. The hospital also had a practitioner, two nurses and 12 stretcher-bearers. During this stage, the capacity of the health centre was 20 beds.

In November 1936, the local Committee of the RC of Valencia was formed by representatives of the political parties and the unions that integrated the Popular Front. The new committee, headed by Dr. Muñoz Carbonero, mentioned above, agreed to the dismissal of Enrique Bonet, doctor and representative of the RC hospital; nevertheless, the revolutionary sanitary authorities remembered Bonet “was squarely dedicated to the Popular Sanitary Committee”, and ratified its destitution. We are, therefore, faced with a conflict of powers between the local CR Committee and the Popular Health Committee.

Another consequence of the war for the hospital was the mobilisation of the personnel. Thus, in April 1937, surgeons José Antonio Borrás and Antonio Fernández Moscoso acted under the orders of Lieutenant Colonel Enrique Gallardo, and were assigned to the hospital of blood of Alfambra, one of many who covered the Healthcare of the injured in the front of Teruel. In January 1938, in the context of the advance of Franco’s troops to the Mediterranean after having reconquered Teruel, Borrás was assigned to the blood hospital of L’Alcora (Castellón). Other mobilised doctors were Víctor Mollà, as the head of a surgical team in the number 1 hospital train, which circulated between Valencia and Sarrión, evacuating injured from the front of Teruel; and Dámaso Segrelles and Miguel Blanes, designated to the blood hospital of Garaballa (Cuenca).

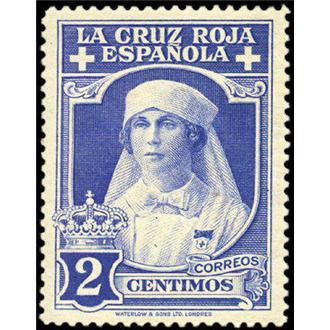

Red Cross auxiliary nurse lady uniform. Source: Borrás, J.A.

El uniforme como signo exterior de la misión humanitaria

de la enfermera auxiliar de Cruz Roja.

Valencia, Imp. Organización Bello, [1948].

The beginning of the year 1939, with the foreseeable victory of the insurrectionists, increased the arrests in Valencia. In this climate of nervousness and uncertainty, the RC focused its efforts on the release of these prisoners. José Antonio Borrás himself was arrested on January 27, 1939 and led to a checa (psycho torture prison) placed at the Escuelas Pías at the Carnissers Street; transferred to the Model prison, was finally released thanks to the efforts made by Muñoz Carbonero. It was not the first time Muñoz visited a prison: during the war he had assisted the inmates of the different prisons of the city of Valencia, Gandia and Alicante, bringing them clothes, medicines, food and authorising the transfer to the hospitals of those who were sick.

The RC Hospital School in Valencia had a scientific vocation that even remained throughout the fight, which resulted in conferences, clinical sessions and publications in medical journals. The Valencian press of the time echoed that. Thus, in the El Pueblo issue of March 7, 1937, it can be read: “In the cycle of conferences organised by this Committee tomorrow Thursday, at six in the afternoon, at the premises of the Hospital, Alboraya, 28, doctor Mr. José Antonio Borrás will speak on the subject «The tolerance of the organism for the war projectiles». The health authorities and the Medical Body of Valencia are invited”. A few days later, Mollà gave a clinical session based on his experience as a first-line surgeon. In addition, Mollà published part of his casuistry in articles published in Crónica Médica (1937 and 1938). Despite the militarisation, the scientific production of Mollà did not banish “civil” illnesses or their specialty, as evidenced by the publication in 1938, in the same magazine, of the clinical case “Bilateral megaureter in an eleven-year-old girl”.

A distinctive feature of this hospital centre was also its teaching vocation. Indeed, shortly after its inauguration, the Red Cross Surgical Sanatorium – as the hospital was known in its original location – began a teaching mission aimed at the training of voluntary women who would eventually receive the title “nurse ladies”. The Red Cross Hospital School of Valencia was born, an institution that had among its objectives, as well as assistance in emergency situations, including extreme poverty, the formation of auxiliary nurses that would help in case of need.

The so-called “nurse ladies” responded to a model, promoted from the Spanish Crown by Queen Victoria Eugenie, who sought to form an auxiliary body of voluntary women who, in situations of humanitarian crisis, especially those derived from natural disasters and armed conflicts, acted according to the doctors’ guidelines and, in short, the RC authorities. According to the decree of creation of this body, from 1917, the sick or wounded should be assisted in a self-sacrificing and altruistic manner in accordance with the needs of the RC, preferably working in hospitals or their own dispensaries. The title, outside the institution, did not have any value and, therefore, did not allow for the professional practice of nursing. The subordination to the hierarchy, the obligation to adapt to the circumstances and the assignation by gender of the tasks – basic treatments of the patients, preparation of the meals, cleaning of the facilities or the instrumental, etc. – were set by a regulation that distinguished between first-class and second-class ladies, depending on the duration of the internship period in hospitals or RC dispensaries.

With the requisites, duties and limitations described, it is obvious that this auxiliary body was reserved for women of the most prosperous classes, that is, the aristocracy and the bourgeoisie. Women who did not aim to enter the labour market, but to take part of their free time acquiring a shiny, prestigious title, in the society of their time, that was manifested by the use of their own uniform and the ostentation with a ribbon with the RC colours, in the image and likeness of Queen Victoria Eugenia, who held the presidency of the institution in Spain. It is revealing that the 1917/60 decree that instituted the status of RC “nurse lady”, as well as the fact that the Basic Law of reorganisation, of 1916, had been published in the section of the Ministry of War in La Gaceta de Madrid.

Portrait of Queen Victoria Eugenie dressed as nurse lady.

Source: La Reina Victoria Eugenia, nurse.

Blog Gomeres. Salud, historia, cultura y pensamiento, University of Granada.

The legislation that led to the reorganisation of the RC subordinated to military health and, in short, the regulations that made the emergence of the auxiliary figure of the nurse lady possible cannot be considered alien to a context of colonial domination of the African continent by the European powers, in particular the distribution of the Maghreb between France and Spain, or the outbreak of World War I, which forced European women to massively occupy vacant posts for the military mobilisation of the male working population.

It is not accidental that one of the first public actions of the Valencian nurse ladies was the assistance to the wounded or ill soldiers – 147 in total – who, from the Rif, accommodated themselves in the so-called Cabanyal Evacuation Hospital. Located in the Fishermen’s Mutual Society building on the Malvarrosa beach, it was prepared on September 15, 1921, as it had already been done in 1909 with the occasion of the war in Africa. Nor is it casual that among the first Valencian nurse ladies the representatives of the local aristocracy stood out, such as the countess of Torrefiel and the daughters of the marquise of Malferit, who would be the president of the local Board of the RC of Valencia until the proclamation of the Second Republic. In addition, the creation of the Hospital School coincided with the arrival of a community of religious, the Capuchin Tertiary Sisters, who after the war were replaced by the Consolation Sisters. They took care of the kitchen and the porter’s lodge, but they also had responsibilities in the polyclinic and nursing field. Everything indicates that, with the incorporation, in the 1920s, of women to hospital activities, as members of a religious community or as nurse ladies, the RC was consolidated as an institution in the city of Valencia.

According to the story of José Antonio Borrás, the head of the training of the Valencian nurse ladies was from the beginning Antoni Cortés Pastor (1891-1935). Specialist in diseases of the respiratory and circulatory system had the collaboration of the rest of doctors of the institution, who taught classes related to their respective specialties. Without a doubt, Cortés Pastor followed the official program, but we could not find out which manual he recommended to his students. Unfortunately, in the summer of 1935 he suffered a fatal traffic accident near Chiva. He was then, from 1931, president of the School of Doctors of Valencia. Probably, the sudden disappearance of the person in charge of teaching and, one year later, the outbreak of the Civil War, caused sooner or later, in circumstances difficult to specify, the closing of the school of nurse ladies. However, we know by José Antonio Borrás that the number of voluntary nurses had experienced a significant increase during the Republic and that one of them, Patrocini Durà, had acquired the consideration, or perhaps the position, of head nurse. It seems that her experience – she knew perfectly well the regulation and the operation of the house – assured the continuity of the school after the Civil War, but we do not have information about its origin and formation, nor on the activities and responsibilities that she assumed within the framework of the institution, especially during the armed conflict. Knowing better this woman’s career would allow to illuminate a moment of crisis of the institution, since the religious community, the Capuchin Tertiary Sisters, had to leave the hospital. After the war, José Oltra Bergón (1898-1956), a specialist in diseases of the digestive system and head of the Hospital’s Digestive Pathology Service, was named “professor of nurses”, a position he held until his death.

What Dr. Borràs did not tell in his Academy of Medicine introductory speech was that the president of the local committee of the RC between 1932 and 1939, the aforementioned Ricardo Muñoz Carbonero (1884-1944), at the end of the war suffered a long painful process, accused of belonging to Freemasonry. Father of the filmmaker Ricardo Muñoz Suay (1917-1997) – the Valencia Film Library is nowadays named after him – was a prominent figure in the city of Valencia: a prestigious doctor and personal friend of Blasco Ibáñez, he had militated in several Republican formations, and held the position of councillor of the City Council of Valencia before the dictatorship of Primo de Rivera. As such, “he defended with gathered data the need for doctors to study our language”. The process ended as a result of his death, in the summer of 1944; he had diabetes and had gone virtually blind.

Xavier García Ferrandis, «San Vicente Mártir» Catholic University of Valencia

Àlvar Martínez Vidal, University of Valencia

Personatges i espais de ciència (‘Science characters and spaces’) is a project of the Unit of Scientific Culture and Innovation of the University of Valencia, with the collaboration of the “López Piñero” Institute of History of Medicine and Science and with the support of the Spanish Foundation for Science and Technology and of the Ministry of Economy, Industry and Competitiveness.

.jpg)