In 1881, the municipal chemical laboratory of Valencia opened its doors and six years later, the one of Alicante. Before the end of the century, we found laboratories open in the city halls of Alcoy (1899) or Dénia (1888). The Valencian municipalities joined an initiative implemented a few decades before by the municipal councils of European cities such as Brussels (1856) or Paris (1878) and that had an impact in Spanish cities such as Madrid (1877), Barcelona (1882), San Sebastián (1884) or Zaragoza (1887). The municipal laboratories were created in all these places as a response to the challenge that for the economy and health of the populations were the new forms of food fraud derived from the incipient industrialisation of the process of production of foods and drinks and the constant extension of the food chain; but, above all, to contain the growing social alarm that all this was causing. The way in which these laboratories were financed and organised, the people who worked on it, the food and drinks on which the focus was placed, and even the analytical methods used, varied considerably from one place to another. That is why we must approach it as much as possible to be able to see them closely and identify all of these factors that ultimately determined the fact that these laboratories ended up being everywhere. This is what we will do with those set up in Valencia and Alicante. We will walk through their streets to discover where they are located in the city and in what type of buildings they were installed, we will ask for permission to enter and see how the spaces destined to house them will be designed and we will leave these to see how they interact with the rest of the city. We will take advantage of these inputs and outputs to check how the access of those who were called to be the main recipients of their services was regulated: merchants and producers, the Administration and, of course, consumers. Observing the form and location of the spaces occupied by the laboratories we will try to understand what these places of science were and meant.

Although the origin, magnitude and economic and hygienic consequences of new forms of food fraud far exceeded the territorial and administrative boundaries of municipalities, especially in cases of port cities such as Valencia and Alicante, the central governments did not hesitate to delegate on the local authorities the responsibility to deal with this alarming problem with their own resources. Thus, the municipal law of 1877 urged the consistory to “perform chemical, physical, micrographic and bacteriological analyses of substances, products and any objects related to food”, without clarifying how and where they should do them. The municipal governments of Valencia and Alicante decided to respond to these regulations by creating their own laboratories and installing them in their own premises, in the consistorial palaces. The laboratories were thus located in the centre of the cities, along with the rest of the administrative and political structures of the municipality and under the shelter and supervision of the highest local authority. We will hurry to visit them, because we know that some of them will not last much in this privileged enclave.

We will make our first stop in the last weeks of June 1887 to go to the town hall of the city of Alicante, where the works for the inauguration of the municipal microchemical laboratory, scheduled for the first days of July, will be finished. We enter the Progreso Square and we are told access there is easy, that we will find it on the ground floor, just where until recently was the office of the almotacén or mostasaf. As it could not be otherwise, we will think. Weights and measures had traditionally been the main sources of fraud in the food and beverage trade. Almotacenes or mostasafs and fieles contrastes had been for centuries the municipal officials in charge of ensuring that the arms of the weighing scales and steelyard balances, the weight of the pounds and arrobas or the volume of barrels and warehouses used in shops were adjusted to those of the patrons kept in the reweight offices. Today we can see these objects in the Museum of the city of Valencia[U1]. Also the quality was inspected and the municipal inspectors were in charge of supervising the conservation status and the hygienic conditions of the drinks and the foods displayed for sale in places and markets. But neither the fiel almotacén nor the inspectors could face the new forms of fraud, impossible to detect with their patterns of measurement or with their senses, however sharp they were. Fraud was no longer only in the quantity or quality of food and beverages but in its composition. And, to detect it, it was necessary to reach beyond the senses. Chemistry had made available to food and drinks producers and retailers a broad and growing variety of substances that would improve the appearance, taste or preservation of low quality products, thereby increasing their benefits. They had sulphates, carbonates and starches to adulterate flour and bread, metal oxides to restore the colour of adulterated chocolate, emulsions of hemp seeds and almonds to return colour and density to watered-down milk, alcohols and artificial dyes to improve low quality wines, mineral acids for vinegar… Chemical adulterations that altered the composition of food and beverages and that could only be detected by chemical analysis. Here is one of the many contradictions with which chemical experts put in front of the municipal laboratories had to fight within these new chemical rehearsals workshops, in which steelyard balances and pounds gave way to the analytical accuracy scales and to the instruments of physical, chemical and microbiological analysis. Let’s go and see them.

The recently appointed director of the municipal laboratory of Alicante, the chemist and professor of Chemistry professor José Soler i Sánchez [U2], seemed satisfied with the progress of the works and hoped to achieve a work space as close as possible to the one he had in the previous months described in a project submitted to the town hall. According to Soler, the locals had enough capacity to house the more than 600 instruments, containers and utensils bought in Paris and Barcelona and that were perfectly ventilated and illuminated. In addition, they had abundant water supply, thanks to the munificence of José Carlos de Aguilera, marquis of Benalua and Grandee of Spain, who yielded thirty cubic meters per year of the waters from his Alcoraia estate, with which the city of Alicante was supplied for some years and the Marquis was able to combine profit and charity. Water whose quality, by the way, Soler himself had certified a few years earlier. Everything was arranged around a large central room, designed to house the main laboratory. There the ovens, the stills and the rest of the chemical analysis equipment would be installed and the collection of flasks, tubes, graduated bottles, burette and the rest of glass instruments would be available on large shelves. Precision scales and instruments for physical analysis such as calorimeters, lactometers, polarimeters and spectroscopes were located in a separate room, away from the street to prevent vibrations from outside and separated from the main laboratory to prevent corrosive vapors from damaging its delicate metallic structures. Soler complained about the lack of a good microscope, which is essential to improve chemical and microbiological analysis, which is increasingly important in controlling food fraud and food hygiene. While waiting for “the new sacrifices of this honourable municipal corporation” to pay off and for a very useful and costly team to be acquired, he could, fortunately, replace it by using the microscope acquired by the Institute of Secondary Education of the city, where he held the Chair of Physics and Chemistry. Access to one of the courtyards of the town hall was also allowed, in order to be able to practice outdoor activities that entailed the release of toxic vapours. Finally, the director had an office allocated to receive the samples and to deliver the reports and certificates to all those who asked for them. As requested by Soler in his project, in this office the library and record books would be installed and from here visitors could contemplate the main laboratory; a very significant detail as we have seen when discovering the laboratories previously designed by Soler.

When the Alicante laboratory opened for business, its Valencian counterpart had already changed of location three times. It settled first on the central offices of the City Council of Valencia, but a few months later it was transferred to the Silk Exchange, an emblematic building in the commercial history of the city and where it only remained a few months. In November of 1882 it was completed the transfer to the last floor of a building on Serrans Street, where the laboratory had to share the space with other services such as the relief home and a children’s school. Although the management of the laboratory was entrusted to the pharmacist Domingo Greus, it was Vicent Peset i Cervera[U3], doctor, Physics and Chemistry professor and member of the Valencian Medical Institute who personified the triumphs and contradictions of that laboratory. He designed the project that inspired its construction and was the one who most bitterly expressed the disappointment for the facilities finally allocated in that “perpetual snow region” of a building away from the administrative centre of the city, where the public presence of the laboratory was diluted between the other services with which it shared the sign of the entrance. Like the one projected by Soler, the laboratory designed by Peset was also organised around a central room, intended to house chemical analysis equipment, special rooms for precision scales, physical analysis instruments and microscopes, warehouse for samples and reagents and an open space for operations with discharge of gases. All this was reduced to a much smaller space, which had to accommodate an important collection of instruments and a team of technicians and operators who did not stop growing in the twenty years that the laboratory remained there.

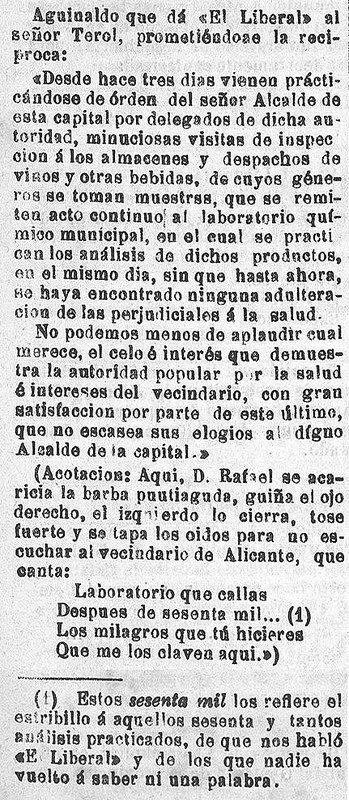

sobre l'activitat del laboratori

químic municipal aparegudes en

la premsa alacantina (El Graduador,

22 de desembre de 1887)

Although the two laboratories shared similar models of organisation and performance, their trajectories in the years in which they were in operation were substantially different. The two consistories had chosen to put at the head of their respective laboratories people of renowned prestige and scientific and professional authority. Soler was elected by unanimous acclamation of a council at that time presided by its brethren and co-father-in-law of the liberal mayor Rafael Terol, while in Valencia it was convened an open competition that Peset won without difficulty. Either way, the laboratories ended up led by experts who had been summoned for years by city councils, governors or courts of justice to issue from their certified private laboratories and expert reports on the composition of food, water, drinks and all kinds of products and substances subject to commercial or judicial litigation. The municipal laboratories made public a service and an activity that until then had been developed in the private field of professional practice. Some complained that it would continue to be, and proposed that the service would be awarded to a person with the necessary knowledge and material resources to do so. The promoters of this option assured that the laboratories could be self-financed by charging producers and traders of the analyses that demonstrated the adulteration or alteration of the composition of their products. In addition to saving for municipal treasury, this option allowed to guarantee the independence of experts and to stimulate the inspection work of the foods and beverages of the market. The councils rejected this type of proposal and opted to integrate the new service within the municipal structures, so that laboratories were under the control and supervision of municipal boards, where producers and traders occupied a large part of the seats and councils.

The way in which this public service was organised varied from one place to another and suffered several alterations over the years in which the laboratories were operational. Although the location and spaces for the Valencian laboratory were not as satisfactory as those achieved by its counterpart in Alicante, the provision of personnel and means was much better, which resulted in greater efficiency. Several chemical analysts and assistants were added to the initial team and a team of inspectors responsible for overseeing places and markets was assigned to the laboratory and collected samples to be analysed. All this contributed to the fact that the number of analyses performed increased over the years, although never reaching a volume of activity according to the population of the city and the quantity and variety of products marketed and consumed daily. The situation was worse in the case of the Alicante laboratory, where the lack of staff, the reduction of the budget and the absence of an adequate inspection system led to the fact that the laboratory became clearly decadent in the few years of its inauguration until it was closed by the end of the century.

The two consistories tried to bring the lab closer to consumers, in an attempt to make them jointly responsible in the fight against food fraud. Thus, rules were established so that any consumer could request for free the analysis of foods or drinks suspected of having had their composition adulterated or altered. But none of this was able to placate the population’s concern about the seriousness of the problem, the outrage over the passivity of local authorities and the doubts about the effectiveness, independence and usefulness of laboratories. The local press in Alicante was especially rich in criticism of the functioning of the municipal laboratory, denouncing the authorities for indulging adulterers, for not arbitrating a system of fines and complaints and to hide the identity of producers and traders of food and adulterated drinks, the lack of an effective system for inspection and sample collection or even the politicisation of the laboratory, presumably more attentive to producers and traders linked to the opposing side of the council.

Everything seems to indicate that these first municipal chemical laboratories were incapable of facing a problem whose scale and geographic extent far exceeded the limits imposed by the material and human resources with which they were endowed and the regulations that regulated their functioning. Far from being designed and equipped as effective tools to fight against food and beverage fraud, the mission of these laboratories seems to have been to appease the growing social alarm and the serious economic and health consequences generated by this problem, but without altering the difficult and unequal political, economic and social balances of which the food fraud was not more than a new manifestation. In the first years of the twentieth century, the municipal laboratories progressively vanished and became part of the municipal hygiene institutes and of an increasingly centralised system for controlling food fraud. But these were other places and other times.

Antonio García Belmar (University of Alicante)

Personatges i espais de ciència (‘Science characters and spaces’) is a project of the Unit of Scientific Culture and Innovation of the University of Valencia, with the collaboration of the “López Piñero” Institute of History of Medicine and Science and with the support of the Spanish Foundation for Science and Technology and of the Ministry of Economy, Industry and Competitiveness.

.jpg)