Juan Negrin. A physician and a prime minister (1892-1956)

|

Juan Negrín. A physician and a

prime minister (1892-1956)

From 24th January to 30th

March 2008

Estudi General Exhibition Room - La Nau

From

Tuesday to Saturday, from 10 to 13.30 and from 16 to 20 h.

Sunday, from 10 to 14 h.

|

|

|

|

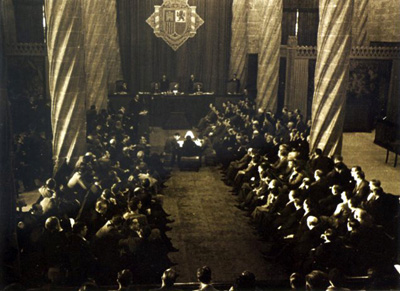

Walter Reuter.

Spanish parliament session at Valencia’s Silk Exchange,

1 October 1937. Juan Negrín, the president of the

government, addresses the members of parliament. |

|

|

|

Organised, produced and promoted by:

Sociedad Estatal de Conmemoraciones Culturales and

Universitat de València

Collaborators:

Fundación Pablo Iglesias

Fundación Juan Negrín

Introduction

The 50th anniversary of the death of Juan Negrín López

was in November 2006. He was an outstanding

physiologist, a socialist, and the last prime minister

of the 2nd Spanish Republic, between 1937 and 1945.

Juan Negrín is said to have been a great figure but one

neglected in Spanish socialism history. Until recently

no literature on his figure had been compiled. This

situation has been partly made up for by a book (Ricardo

Miralles, Juan Negrín, La República en guerra, Temas de

Hoy, Madrid, 2003) focused on his most important period,

the Civil War, and by a short biography by Gabriel

Jackson in Ediciones B (Gabriel Jackson and

Víctor Alba, Juan Negrín).

According to the exhibition’s curator, Ricardo Miralles,

“the biography of Juan Negrín (1892-1956) continues to

raise controversy, despite the many years since his

death. In his time, his supporters underlined his high

stature as a statesman, while his detractors reduced his

qualities as a ruler to nothing, portraying him as the

worst traitor secretively devoted to Communism, a

spurious cause. For today’s historians, both flattering

defence and nonnegotiable condemnation lead any attempt

of veracity on Negrín's figure to no results whatsoever.

Indeed, the difficulties in approaching his figure –an

unnecessary outcome of the complex historical times he

lived- cannot admit a simplification to belligerent

schemas. That’s why I think that insisting on the good

or bad qualities of the character is a totally unfertile

intellectual exercise. Even so, debates are always

better than ignorance or silence. Silence about Negrín

was indeed made absolute as from his death in Paris in

1956, 50 years ago".

Presented at the University of Valencia, the exhibition

aims to repair this historical oblivion and mutilated

memory and to provide new generations with information

that was missing to date. |

|

|

|

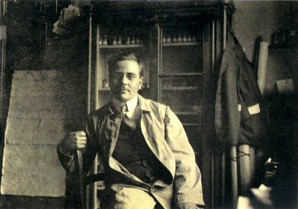

Juan Negrín at the laboratory of the Physiology

Institute of Leipzig. |

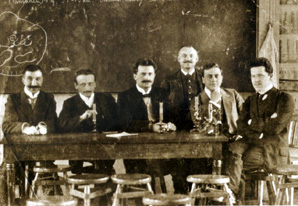

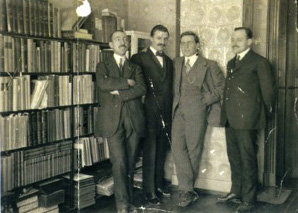

Juan Negrín in Leipzig, Germany, with colleagues from

the Physiology Institute. |

|

|

|

Summary of the Exhibition

Juan Negrín López was born in Las Palmas de Gran Canaria

on 3rd February 1892, in a well-off family. After

completing his high education, when he was just 16, he

travelled to Germany to do a medical degree. He

completed his PhD at the University of Leipzig. Negrín

introduced in Spain the latest research in physiology

together with Santiago Ramón y Cajal, who recommended

him for the commission and management of the Physiology

Laboratory, at the basement of the Residencia de

Estudiantes of Madrid. After validating his studies

in Spain, in March 1922, when he was 30, he became

Professor in Physiology by Madrid's Central University.

In the development of his post in the medical college,

he organised the physiology lab.

Negrín joined the Spanish Socialist Party in May 1929

and, from the proclamation of the Republic, he

concentrated on politics, dropping out from medical

practice and academic activity. He was elected member of

parliament during the three republican terms, aligning

himself with the “central” fraction of the party, headed

by Indalecio Prieto, a very close friend to him until

the end of the civil war.

At the onset of the fratricidal conflict, Negrín was

appointed Chancellor of the Exchequer under the rule of

Francisco Largo Caballero. His name has been associated

with the transfer of gold reserves from the Bank of

Spain to the Soviet Union ever since. The black legend

on "Moscow's gold" started then, Negrín being turned

into the servile executor of orders from Moscow. The

first government of Juan Negrín was constituted on 17

May 1937. No matter how much Azaña’s personal diary made

clear that it was him personally who gave Negrín the

power, the chapter about his promotion to prime minister

has been linked to murky business from Moscow. |

|

|

|

Federico García Lorca looking through the microscope. |

From left to right, Julio Guzmán, Enrique Moles, Juan

Negrín and another friend in Leipzig, 1911. |

|

|

|

With the passing of time and the republic defeats in the

battlefield, Manuel Azaña and Juan Negrín fell out.

Azaña himself explained later the difference that

separated his concept of resistance politics at the time

from that of his prime minister. According to him, the

Republic’s dilemma was never “resistance or surrender”.

The difference was between “resisting is winning /

resisting is the only possible policy”, which Negrín

supported, and his very conviction that the war was

inevitably lost from the start and, consequently,

“resisting had to be a way of reaching the peace". Both

conceptions turned incompatible.

Under the internationalisation circumstances of the

civil war, the real materialisation of resisting until

the end -advocated by Negrín- would have been impossible

without foreign help. As a consequence, Negrín’s policy

led to international dependence on the USSR and the

unprecedented protagonism of the Spanish Communist

Party.

In the long run, the identification of the Communist

Party with the resistance policy fostered by Negrín

caused the remaining political forces -parallel to the

waning possibilities of the Republic- to reject the

communists (rather openly in the end) and subsequently

Negrín. Therefore, with successive military defeats, the

internal political homogeneity of the government and the

Popular Front first collapsed and finally blew up.

In fact, the fundamental problem, loyalty-wise, was the

evolution of the war and the fact that this was

unfavourable to the Republic all along. As military

defeats were taken in, in some political forces

–republicans, nationalists, and socialists opposed to

the Negrinist faction of the Socialist Party- but

also among the military, the idea spread that it was

them who had to take over the Republic’s government,

perhaps imagining a possible understanding with the

enemy to put an end to war, getting rid of Negrín, and

having France and Great Britain as mediators. None of

this was possible. With or without Negrín, Franco’s

determination was always of total victory and

consequently of unconditional defeat.

In his immediate exile, Negrín did not manage to control

the centrifugal tendencies of republicans and

socialists, and his government -in office until 1945-

was contested by different sectors. It is unavoidable to

say that Indalecio Prieto (a genuine political mentor to

Negrín in the 1930s) became his most implacable critic.

On Negrín’s death, however, he deeply regretted not

having made up with him. |

|

|

|

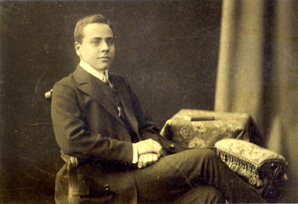

14-year old Juan Negrín, in Germany. |

Negrín reporting on the intervention of fascist forces

in the Spanish War, General Assembly of the League of

Nations, Geneva. 14 September 1937 |

|

|

|

Catalogue

The exhibition is complemented by a catalogue with

materials that support the exhibits and which include a

number of scientific papers written by the best

specialists ex novo. This is the list of the

articles:

Ricardo Miralles, Juan Negrín, un socialista silenciado

Josep Lluís Barona, Negrín, médico fisiólogo

Julio Aróstegui, La guerra civil española. Conflicto

moderno, solución antigua.

Enrique Moradiellos, El acceso de Juan Negrín a la

jefatura de gobierno y la reconstrucción del Estado: su

primer año

Ángel Viñas, Juan Negrín, la cuestión del oro y la

economía de guerra repulicana

Gerald Howson, Armas para la República Española

Daniel Kowalsky, Los rusos en España

Antonio Elorza y Marta Bizcarrondo, Juan Negrín, entre

dos comunismos

Michael Alpert, Negrín y el ejército

Ricardo Miralles, Diplomacia para una guerra

Enric Ucelay-Da Cal, Negrín en Cataluña: nadie perdona a

un perdedor

Santos Juliá, Azaña y Negrín con Madrid al fondo

Helen Graham, Negrín contra Prieto: una crisis en tres

actos

Paul Preston, Razones para la resistencia: la represión

franquista en zona nacional

Gabriel Cardona, Las razones de Negrín para resistir

Ángel Bahamonde Magro, Casado versus Negrín. El

síndrome del abrazo de Vergara

Juan Francisco Fuentes, Negrín y la división del

socialismo español en el exilio

Sergio Millares, Los papeles de Negrín

“Yo

lo conocí”, a selection of short texts by: Carmen

Negrín, Santiago Carrillo, Francisco Ayala, Ramón

Lamoneda y Marxina Lamoneda, Francisco Guerra, Aurora

Arnáiz Amigo, Eulalio Ferrer and Juan Martín Tundidor

López. |

|

|

|

Portrait of Juan Negrín during his stay in Germany.

Photographer: Ernst Sandau, Berlin. |

|

|

|

Documentary produced on the occasion of the exhibition

TITLE

Juan Negrín.

Resistir es vencer.

CO-PRODUCED BY

SECC+TVE+Fundación Pablo Iglesias

YEAR

2006

SYNOPSIS

Juan Negrín, a scientist and

a politician, was the President of the last Government

of the 2nd Republic of Spain. Apart from a human and

professional portrait, the documentary covers the famous

story of Moscow’s Gold and the last days of the Civil

War, including Segismundo Casado’s coup d'état.

LENGTH

52 min

FORMAT

Digital Betacam 16:9/DVD

GENRE

Documentary

Curator

Ricardo Miralles, Contemporary History Professor from

the University of the Basque Country, is a specialist in

the History of the Worker Movement and Spanish Socialism

in particular. Among other works, he is the author of:

El

socialismo vasco durante la II República, Bilbao 1988;

Indalecio Prieto. Textos escogidos, Oviedo, 1999; Juan

Negrín. El hombre necesario, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria,

1996; and Juan Negrín. La República en guerra, Madrid

2003.

He has also researched on International Affairs History,

with the publication Equilibrio, hegemonía y reparto.

Historia de las relaciones internacionales entre 1890 y

1945; He has published numerous papers on international

politics during the Civil War period in different

national and international journals.

For more information:

http://www.secc.es/ficha_actividades.cfm?id=1040 |

|

|

|

Negrín in France, 1950s; his heart condition was already

serious. |

|

|

|

|