The University of Valencia (UV), together with the Foundation for the Promotion of Health and Biomedical Research of the Valencian Community (Fisabio), the Higher Council for Scientific Research (CSIC) and the Centre for Online Biomedical Research (CIBER), has participated in the first genome sequencing study of the Demodex folliculorum mite, the only animal living in symbiosis with the human body. The research, published in the journal Molecular Biology and Evolution, has been led by Bangor University and the University of Reading.

These are mites that are transmitted at birth, are carried by almost all humans and their number reaches a maximum in adults as the pores grow. They are about 0.3mm long, found in hair follicles on the face, nipples, and eyelashes, and feed on the sebum naturally released by pore cells. They are activated at night and move between the follicles in search of mating.

One of the main results of the work is that this mite survives with a minimum number of genes. “The loss of essential genes for DNA repair and the lack of exposure to possible partners that could add new genes to their offspring may have led D. folliculorum to an evolutionary dead end and possible extinction”, explains Andrés Moya, researcher from the Genomics and Health Area of Fisabio, Full Professor of Genetics at the University of Valencia and author of the article. The expert also adds: “although these phenomena were already known to occur in symbiotic bacteria, the study demonstrates this for the first time in animal eukaryotes”. In the article, Amparo Latorre, Full Professor of Genetics of the UV, also participates.

Alejandra Perotti, full professor of invertebrate biology at the University of Reading, who has co-directed the research, states that “these mites also have a different arrangement of genes than other similar species, because they have adapted to a protected life inside the pores. These changes in their DNA have led to some unusual body features and behaviours”.

The work explains that, due to their isolated existence, without exposure to external threats, without competition to infest hosts and without encounters with other mites with different genes, genetic reduction has caused them to become extremely simple organisms with tiny legs propelled by only 3 unicellular muscles. They survive with the minimum repertoire of proteins, the lowest number ever seen in this and related species.

This genetic reduction is also the reason for their nocturnal behaviour, according to the study results. The mites lack ultraviolet protection and have lost the gene that makes animals wake up in daylight. They are also unable to produce melatonin, a compound that makes these small invertebrates active at night. However, they are able to fuel their nocturnal mating sessions using the melatonin that human skin secretes at dusk.

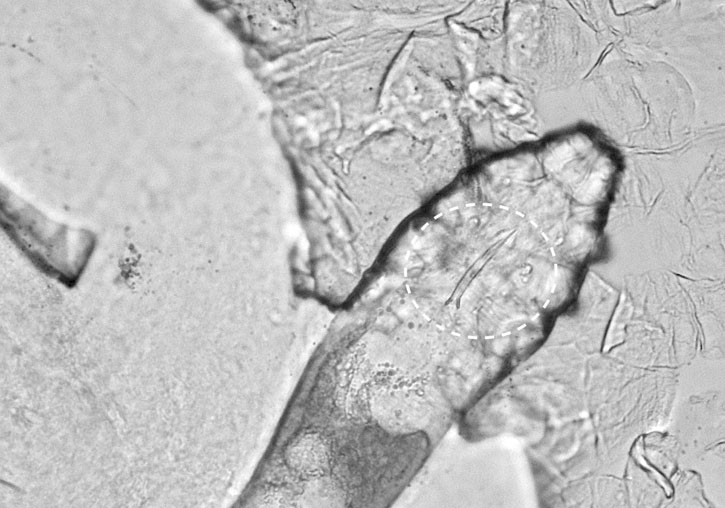

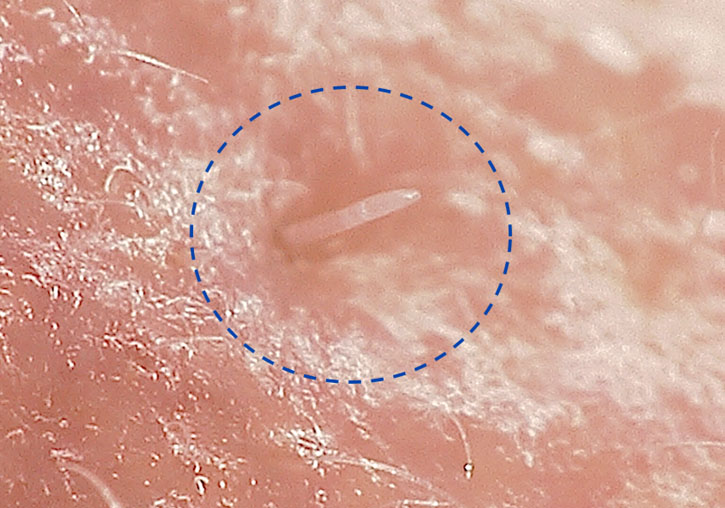

The research also explains that their unique genetic makeup gives rise to the mites’ unusual mating habits. Their reproductive organs have been moved forward, and males have a penis that protrudes upwards from the front of their body, meaning they have to get under the female when they mate, and copulate while both hold on to human hair.

Another of the research findings is that one of their genes has been inverted, which gives them a particular arrangement of mouthparts that protrude to collect food. This helps their survival at a young age.

Furthermore, these mites have many more cells at a young age compared to their adult stage. This contradicts the earlier assumption that parasitic animals reduce their cell numbers early in development. The researchers state that this is the first step for the mites to become symbionts.

To date, some studies have assumed that mites do not have an anus and therefore must accumulate all their faeces throughout their lives before releasing them when they die, which causes inflammation of the skin. However, this study confirms that they do have an anus, which is why many skin conditions have been wrongly attributed to them.

Article: Gilbert Smith et al. «Human follicular mites: Ectoparasites becoming symbionts». Molecular Biology and Evolution, msac125, https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msac125

Annex photo caption:

Demodex folliculorum mite penis.

Images: