El temps suspés: els camps de persones refugiades palestines al Líban (Suspended time: Palestinian refugee camps in Lebanon) is a project of social communication to bring the general population, young and old and with no distinction of sex or origin, closer to the reality of the population, mainly Palestinian, that lives in the refugee camps for Palestinians in Lebanon.

The main axis of the proposal is a photo exhibit by the photojournalist Germán Caballero, around which the rest of the project revolves: film and documentary screenings and round tables.

Palestinian people have lived in a continuous diaspora for over seventy years. 1948 was the year of the creation of the State of Israel, but it also was the Palestinian Nakba year (“catastrophe” or “disaster” in Arabic). Around 750,000 Palestinian were forced out of their homes and land through what we know call ethnic cleansing. According to the latest studies, 615 Palestinian towns were wiped out and/or their native Palestinian population was thrown out. This cannot be put down to chance; the Zionist movement, which did not and does not represent Judaism or Jews, had been colonizing Palestine since the late XIX century. At that time Palestine was part of the Ottoman Sultanate, but after it was defeated in World War I, the United Kingdom annexed Palestine to its empire and supported Zionism. After World War II, the UK decided to abandon Palestine and the UN intervened. This was the appropriate context that the Zionist movement had been waiting decades for with the aim of creating an exclusively or mainly Jewish colonial state in the maximum possible Palestinian land. This was the main reason behind Nakba.

Thus, most Palestinians –Muslim, Christian or from any religion– became refugees. They were scattered in about 40 camps that were provisionally set up in the nearby Arab countries of Lebanon, Transjordan –then Jordan– and Syria, as well as in the West Bank –including in East Jerusalem– and the Gaza Strip, the only two Palestinian territories that were not occupied by the Israeli-Zionist forces in 1948 and that remained in Transjordinian and Egyptian hands, respectively, until 1967. The West Bank, the Gaza Strip and their refugee camps have been under military occupation and colonisation by the State of Israel since 1967. Israel continues to seek as much territory as possible with the minimum Palestinian population possible and is succeeding in making “the land get narrower” –as the Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish wrote– for Palestinians. In short, this is the longest-lasting refugee situation in contemporary history.

The UNRWA –a UN agency created in 1949 to address the needs of Palestinian refugees that now plays a crucial role in providing them with education and food– currently assists more than 5,000,000 Palestinians. Due to the Palestinian diaspora over the years, it has spread around the world, beyond the countries of the Levant.

Palestinian refugees are deemed to be “those who lived in Palestine on a regular basis between January 1st of 1946 and May 15th of 1948 and who lost their homes and livelihoods as a result of the 1948 conflict”. The descendants of those who have not been able to return to their places of origin are also nowadays considered Palestinian refugees. Although the UN General Assembly stated in the Resolution 194 of 11/12/1948 that refugees had and have the right to return to their homes, the State of Israel has refused to enforce this right since 1948.

One of the first displays of symbolic resistance to Nakba by the Palestinian refugees was the naming of new neighbourhoods, streets or sections of refugee camps. This was the case, among others, of the Shatila camp in Lebanon, where various names of its internal organisation referred to the Palestinian towns from where the displaced Palestinians came. Similarly, from 1947 onwards, it became customary to name Palestinian girls after towns such as Baysan, Haifa, Zefat, Jaffa, Janīn or after Palestine itself (Filasṭīn or Falasṭīn in Arabic).

This was the context in which refugees lives, “waiting” to return home. This period, this wait, was considered to be “suspended time”, but as time went on it began to become an endless provisional period, an “eternal present”. Nakba was not only present; it was “the present”.

Specifically, Lebanon was the destination of many Palestinian refugees during Nakba year. It is worth noting that Lebanon was and continues to be the most religiously diverse country in the Levant. During the Nakba period and up to this day between 15 and 20 different religious groups live there, mostly Islamic and Christian. The largest were and are Sunni Islam, Shi’ism and Maronite Catholic Christianity. The balance of power between them was fragile and problematic, as the colonialism of the French Mandate (1923-1946) developed different strategies to deepen their divisions and favoured the Christian sectors.

Els palestins i les palestines del Líban no han arribat mai a ser considerats ciutadans i ciutadanes de primera com la resta de persones libaneses. Han desenvolupat un paper fonamental en el país -moltes vegades com a mà d'obra barata- i van tindre un paper destacat en la Guerra Civil Libanesa (1975-1990). Tanmateix, van pagar molt car veure’s involucrats i involucrades en aquest conflicte bèl·lic. Milers de persones palestines refugiades van ser assassinades durant la guerra, i van patir atrocitats i massacres com les de Karantina, Tel al-Zaatar i la més coneguda, la de Sabra i Xatila del 1982. Es calcula que, durant tres dies, milers de civils palestins van estar assassinats a Sabra i Xatila a mans de paramilitars d’extrema dreta de la Falange Libanesa amb la connivència de l'exèrcit d'Israel.

In any case, Palestinian refugees have played a decisive role in the political and social construction of Lebanon country since Nakba. Provisional refugee camps soon became permanent. Refugees went from tents to cement for a situation that was presented to them as provisional and that continues to this day with no prospect of improving.

Palestinians in Lebanon have never been considered first-class citizens like the rest of the Lebanese. They have played a key role in the county –many times as cheap labour– and had a prominent role in the Lebanese Civil War (1975-1990). However, they paid dearly for their involvement in the armed conflict. Thousands of Palestinian refugees were killed during the war and suffered atrocities and massacres such as those of Karantina, Tel al-Zaatar and the most well-known, the Sabra and Shatila massacre of 1982. It is estimated that, for three days, thousands of Palestinian civilians were killed in Sabra and Shatila by the far-right paramilitary of the Lebanese Phalange with the acquiescence of the Israeli army.

Moreover, Palestinian refugees in Lebanon need a work permit in order to enter the job market (which many people can’t afford) and are not allowed to practice 70 professions reserved for the Lebanese. They also don’t have access to a passport or to Lebanese nationality; they only hold a document with the title “travel document for Palestinian refugees in Lebanon” written in in Arabic and English. Furthermore, they can only access the public education and healthcare provided by the UNRWA and widespread precariousness prevents them in many cases from pursuing higher education.

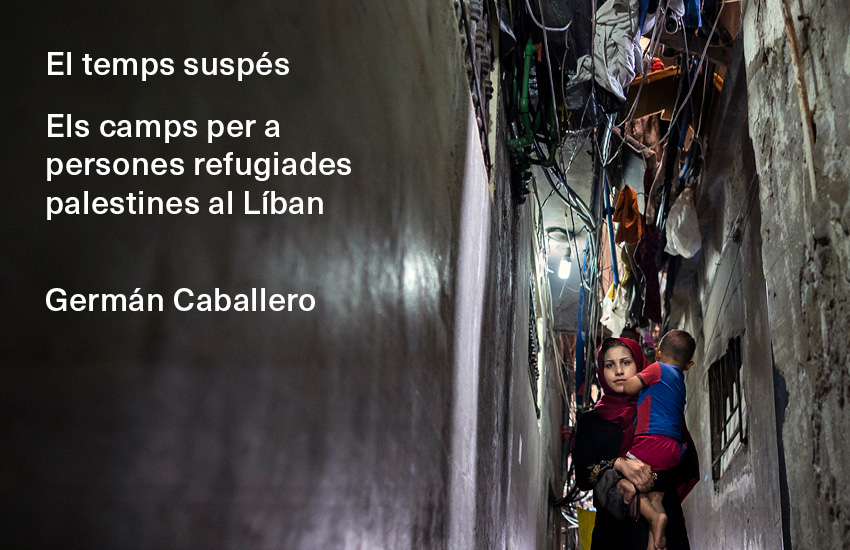

Refugee camps are nowadays precarious neighbourhoods in Lebanese cities, a kind of ghettos where thousands of people are crowded together in inhumane conditions without access to safe drinking water. The camps were originally intended for Palestinians on a temporary basis, but are now inhabited by Syrian refugees fleeing war in their country and by other vulnerable nationalities in Lebanon, such as people from Bangladesh who can’t afford to pay rent outside the camps.

The original boundaries of the camps have not been modified since they were built, so the space is the same but the population living there has multiplied. For example, the Shatila camp in Beirut was designed in 1949 for 500 family units and, according to the UNRWA, over 10,000 people lived there in 2018. The Burj Barajneh camps was created in 1949 for 3,500 people, but the UNRWA currently estimates that it holds almost 20,000 refugees. This has led to vertical growth without any urban planning, green spaces or recreational areas for children or sports. There is also a lack of basic infrastructures (besides drinking water) such as wastewater management or a lighting grid.

These living conditions cause many wide-ranging problems. The population suffers from physical and mental health issues due to the lack of basic infrastructures and the crowds. In addition, most people are not highly educated and can’t access many or all prohibited professions (except cleaning jobs or farm work for Syrians), which causes precariousness and poverty. The desperation of young people who face this reality is also well-known. Their situation leads them to emigrate or drives them to problems that are increasingly common in camps, such as drug addiction.

Similarly, gender inequality is also prevalent. Women are generally responsible for reproductive and domestic work and men for paid work. Significant disparity between men and women also exists in public spaces and in political or social positions in the camps, which are mostly occupied by men.

One of the most dangerous parts of the camp is the precarious and chaotic lightning grid. There are all kinds of wires hanging all over the camp, which often cause explosions, fires and deadly electrocutions. Another danger are the precarious homes, many of which were not built by professional builders, but by the same people who seek refuge and have no alternative. The partial or total collapse of the houses also causes accidents. Every age range suffers from precariousness in the camps: elderly people don’t have public pensions or subsidies, so they have to work or live off younger relatives.

Internal political tensions in the camps also result in dangerous situations among the people who live there. Camp security is currently handled by Palestinian militias, with the exception of the Mieh Mieh camp. Most camps have open access, but in the south of Lebanon the camps near Saida and Tyre are closed with controls by the Lebanese army. The same thing happens in the northern camp of Nahr el-Bared in Tripoli.

At present, the social and economic situation in the refugee camps for Palestinians in Lebanon is extremely difficult, as it is in some aspects in the rest of Lebanon. There are many recent causes. First of all, political instability has been a constant since the government elected at the polls –with Prime Minister Rafig Hariri at the helm– resigned en bloc on the 29th of October of 2019, after weeks of protests in the streets with massive following. A provisional government of technocrats, with Michel Aoun as president, seized power. However, they resigned after the explosion of the Beirut harbour in 2020 and the precarious economic situation. Finally, in October 2020, Rafiq Hariri returned to power despite loud protests in the streets.

Secondly, the economic crisis is severe. The Lebanese pound has lost much of its value against the US dollar, the currency in which imports are paid. This has increased the prizes of basic commodities and led to hyperinflation, leaving 50% of the population in poverty and with a 35% unemployment rate.

Thirdly, social problems have arisen from the arrival of hundreds of thousands of Syrian refugees (some sources report more than a million). Lastly, the recent COVID-19 epidemic and its socioeconomic consequences on the weakest population, as well as the explosion of the Beirut harbour in August 2020 have contributed to the instability, unrest and tension. If the situation in Lebanon is generally very complicated, the one in the camps is dire.

Jorge Ramos Tolosa is a professor and doctor of Contemporary History from the University of Valencia. His doctoral thesis received an International Reference, as well as the Extraordinary Doctoral Award. He is the author of “Los años clave de Palestina-Israel” (Marcial Pons, 2019), “Palestina. Una història essencial” (Sembra Llibres, 2020) and “Una Historia contemporánea de Palestina-Israel” (Los Libros de la Catarata,2020)

© Germán Caballero