COMPLEMENTARY ACTIVITIES

1: REGISTRATION GUIDED TOURS

2: Cycle "Manuel Sanchis Guarner: València 1972. 50 anys després"

In 1972, Manuel Sanchis Guarner published his book La ciutat de València. Síntesi d’Història i Geografia urbana (“The city of Valencia. Synthesis of History and Urban Geography”), Círculo de Bellas Artes, Valencia. This book changed the perception of the urban evolution and heritage of the Valencian capital. The publication opened a prosperous period of modern and advanced studies on architecture, archaeology, urban geography, history, literature and even festivals and traditions, which was immediately revived by Sanchis Guarner in his book. Moreover, the book ushered in a new movement of appreciation for a city that had to be preserved and protected from destruction.

On the fiftieth anniversary of that publication, it is worthwhile to acquaint new generations not only with the figure of the master Sanchis Guarner and his work, but also with the city of 1972 in which he wrote this fundamental work. What was the city like in 1972 and how has it changed? What were the most relevant urban and social issues at that time? Why did Sanchis Guarner write this kind of book?

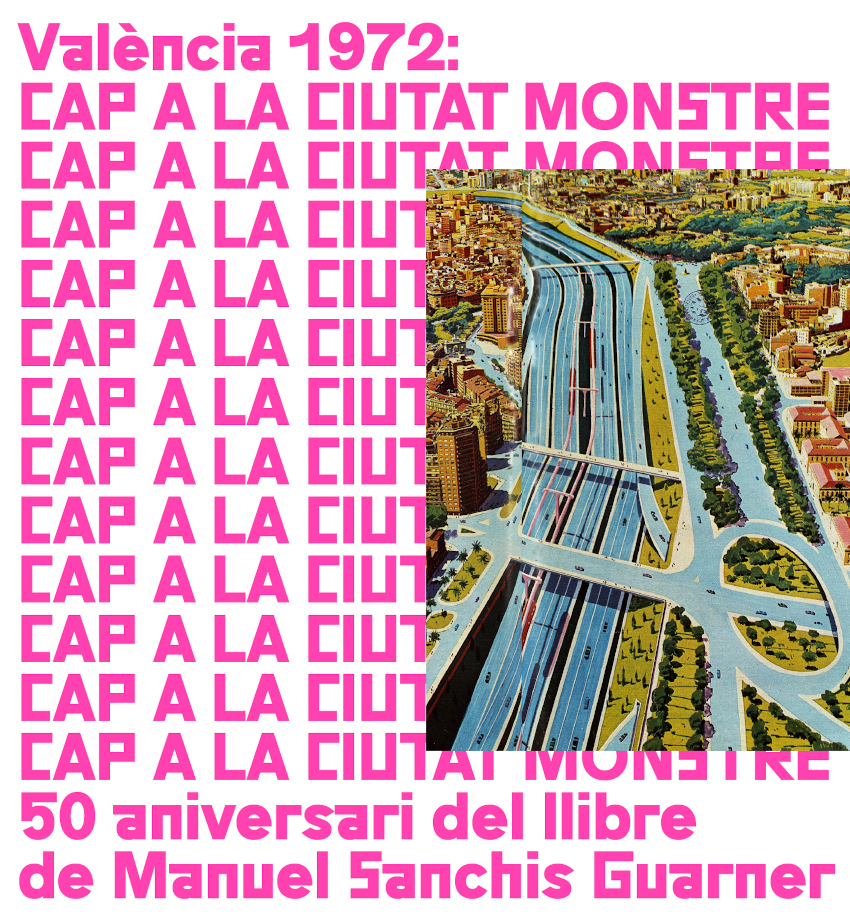

To understand the major contribution of La ciutat de València. Síntesi d’Història i Geografia urbana we need to know what was that city like and what were its main concerns. The exhibition attempts to convey a panorama and an experience that may surprise many of the current inhabitants of Valencia. At the same time, it offers interpretative keys to discover its evolution up to the current situation and to show the urban and constructive dynamics that were taking place at that time. The title Hacia la ciudad monstruo (“Towards the Monster City”) is taken from a conference given in 1972 by the architect Salvador Pascual Gimeno, in which he warned of the fate that awaited the city if it did not reverse the urbanising and destructive dynamics of the 60s, dynamics to which Salvador Pascual himself had contributed.

Sanchis Guarner wrote his book at a time when the city of Valencia was beginning to sense the effects of developmentalism and the unbridled urbanisation resulting from a highly debatable general plan of 1966, adapted to the Southern Plan for the diversion of the Turia riverbed after the flood of 1957. In short, the main topics of debate at the time showed the problems that this dynamic was already causing: the urbanisation of the Saler and the effect on the Dehesa and the Albufera, the possible conversion of the Turia riverbed into a rapid communication highway and the destruction of the historic centre. The construction of the new Turia riverbed (derived from the Southern Plan, started in 1972) had already shown the consequences that any of these projects could have for the city.

SECTION 1

The city of Valencia, around the 70s, was very different from what it is today. Thanks to numerous graphic and audiovisual testimonies from those years, we can delve into a sensory experience to relive that capital of half a century ago. Cars as the new protagonists of the urban space, the presence of General Franco and his regime, the celebration of Iberflora, the works associated with the Southern Plan, the Fallas of the time, the beginnings of tourist development, the first concerns about the consequences of economic and urban development on nature appear in official news reports or in private family testimonies.

SECTION 2

What was Valencia like in 1972? Some comparisons will allow us to get a better idea of the reality of the time. The differences between the cost of some products are related to the salaries of the time and the high cost of living, but others give us an idea of what was that city like compared to today's city.

- Hacia la ciudad monstruo was a phrase uttered in 1972 by the architect Salvador Pascual Gimeno at a conference on the future of Valencia. Although Pascual had contributed to the situation he was now denouncing with some of his creations, the phrase perfectly defines the feeling in Valencia at that time after the Southern Plan construction operation and the gigantic projects that the city had in sight.

- The city of Valencia during the 70s and today. The differences between the aerial images show the evolution of the urbanised space and some of the areas where the changes have been most evident: the old Turia riverbed, the historic centre, the huerta (Valencian irrigated region), the new streets and avenues... The transformation of the urban space is evident.

- Salvador Pascual Gimeno's statement about the danger of Valencia becoming a monster city was undoubtedly influenced by the experience of the Southern Plan project in Valencia in the sixties, with the construction of the new Turia riverbed. This project, which changed the landscape of the southern huerta of Valencia forever, was carried out with great territorial consequences, efficient construction and destructive procedures, a great deal of social control of those affected and a technocratic language that justified the operation.

- What was Valencia supposed to be like in 1985: a monster city? Between May 1968 and September 1970, the journal Gaceta Ilustrada, edited in Barcelona, published a series of reports on what certain Spanish cities would be like in 1985. Mario Gaviria, Françoise Sabbah and Juan Manuel García Morales were in charge of the texts and coordination, while Antonio H. Palacios did the drawings illustrating the reports with photographs by Calderón. In particular, the one for the city of Valencia appeared in September 1968. The press clipping reflected practically all the urban projects underway, integrating them into a modernising discourse that was fully coherent with the developmentalist spirit of those years and representing them with futuristic illustrations that gave us an idea of what would the city be like if these projects were carried out. The title of the section presenting the project of a highway running along the Turia riverbed was openly praised: “The water road turned into a petrol road”.

SECTION 3

Valencia showed two very different faces in 1972. On the one hand, the propaganda of the Franco regime continued to insist on a traditional, national-Catholic social image, economically evolved but anchored in the control mechanisms of the dictatorship. On the other hand, an insurgent artistic expression was growing, with a ground-breaking formal language, which sought to express its rejection of the politics of the time and the lack of freedom in Spain, as evidenced by some of the works presented here. This section is a reminder of the 7th Spanish Metal Art Fair held in Valencia from 8 to 17 April 1972, which brought together some of the most innovative works on the sculptural scene at the time. Just one month later, from 22 to 28 May, the 8th National Eucharistic Congress was held in Valencia, presided over by General Franco and the then Prince and Princess of Spain. Two ways of understanding Spain.

SECTION 4

- The General Plan of 1966. Valencia had its first general plan of urban planning in 1946. Twenty years later, in 1966, a new general plan, which included the Southern Solution of the new Turia riverbed following the floods of 1957, was approved. This plan had a great territorial impact, as it significantly increased the land classified as urban and developable and planned a large road infrastructure. Its legacy, in the form of urban densification and expansion, congestion and lack of facilities, survived until the democratic city councils of 1979 and the new general plan of 1988. And even some of its provisions survive today.

Three were the great debates of the time: the urbanisation of the Saler, the conversion of the old Turia riverbed into a highway and the progressive destruction of the historic city centre.

- The Special Plan for the Urban Development of the Dehesa del Saler. Although the Special Plan dates from 1965, it was not until 1967 that the first works were awarded. The plan consisted of the construction of a 2,600-metre-long seafront promenade, the division of more than one million square metres of natural space into 1,076 plots for private construction, the planning of 32 luxury hotels and another 160 of a lower category, 3,000 flats and 6,000 houses in coastal areas, a port, heliport, congress hall, sports facilities, schools, chapels, service stations and commercial and leisure areas. In order to create an access, the Saler highway, still in use, of 7.6 km long and about 35 metres wide, was built, as well as a National Parador and a golf course.

As early as 1970, this project was opposed by the Sciences Faculty of the Universitat de València, organisations such as the Association for the Defence of Nature (ADENA), the naturalist Félix Rodríguez de la Fuente, citizens' groups and several media outlets. In spite of this, the urbanisation progressed, although not at the desired pace, until it could be stopped under the democratic city councils.

- The highway on the river. As early as 1958, the conversion of the old riverbed of the Turia into a communication artery was proposed in connection with the construction of another new riverbed, thanks to what was known as the Southern Plan. The idea was to occupy the old riverbed with a highway at a lower level than the rest of the city, which was to link Madrid and Alicante with Barcelona and with the airport, the port and El Saler. The plan envisaged a road almost 30 metres wide with up to six lanes and junctions at different levels to connect with the streets of the city. The strong citizen opposition, “El llit del Túria és nostre i el volem verd” (“The riverbed of the Turia is ours and we want it green”) and, in particular, from the newspaper Las Provincias, led to the reconsideration of this plan at the highest levels of government as early as 1973. Finally, in 1976, the old Turia riverbed was returned to the city.

- The destruction of the historic city. The scant protection afforded to the historic centre by Valencia's various urban development plans, together with the lack of social sensitivity and the predominance of a predatory urban planning, meant that after the Spanish Civil War, a process of heritage destruction of the inherited historic urban landscape began. Between 1950 and 1980 alone, around fifty buildings of great value disappeared from the city centre. Palaces, convents, churches, barracks, hospitals, chapels, schools, mansions..., but also medieval squares and streets and even theatres, warehouses and buildings from the late 19th and early 20th centuries, gave way to modern buildings that were depersonalised and sometimes disproportionate to their urban environment, as well as streets adapted to cars.

L’autopista pel riu. Des de 1958, ja s’havia proposat la conversió del vell llit del Túria en una artèria de comunicació relacionada amb la construcció d’una altra nova llera, gràcies al conegut com Plan Sur. Es tractava d’ocupar l’antic caixer amb una autopista de cota inferior a la de la resta de la ciutat, que havia d’unir Madrid i Alacant amb Barcelona i amb l’aeroport, el port i el Saler. El pla preveia un vial de quasi 30 metres d’amplària amb fins a sis carrils i enllaços a diferent nivell per a connectar amb els carrers de la ciutat. La forta oposició ciutadana (“El llit del Túria és nostre i el volem verd”) i, en especial, del diari Las Provincias, va fer que ja en 1973 es reconsiderara aquest destí des de les més altes instàncies governamentals. El 1976, per fi, es produïa la cessió de l’antic llit del Túria a la ciutat.

La destrucció de la ciutat històrica. L’escassa protecció que els diferents plans urbanístics de València atorgaren al centre històric, junt a la falta de sensibilitat social i el predomini d’un urbanisme depredador, feren que després de la Guerra Civil espanyola començara un procés de destrucció patrimonial del paisatge històric urbà heretat. Només entre 1950 i 1980 desapareixeran al centre de la ciutat mig centenar d’edificis d’alt valor. Palaus, convents, esglésies, casernes, hospitals, capelles, col·legis, casalots..., però també places i carrers medievals i, fins i tot, teatres, magatzems i edificis de finals del xix i principis del xx, cediren el seu espai a construccions modernes despersonalitzades i en ocasions desproporcionades per al seu entorn urbà, així com a carrers adaptats als automòbils.

SECTION 5

Manuel Sanchis Guarner (Valencia, 1911-1981) was the author of a book, La ciutat de València. Síntesi d’Història i Geografia urbana (1972, Círculo de Bellas Artes), which can be seen as a reaction to the urban dangers threatening Valencia in the late 1960s and early 1970s. His work, published in Valencian, awakened urban awareness in broad social sectors and especially among professional men and women in the fields of geography and architecture. This book not only made many inhabitants aware of the history of their own city, but also warned them of the serious dangers to their cultural heritage and made visible subjects linked to the history of Valencia such as architecture, archaeology, ethnology, traditions, literature, folklore and the evolution of artistic trends.

Manuel Sanchis Guarner was an outstanding philologist and writer, trained in the teaching environment of Menéndez Pidal. Exiled and repressed because of his military status in the Republican army, he was not able to enter the university until the 1960s as a non-tenured lecturer, obtaining the post of full university professor in 1979. His work on the Valencian language helped to dignify it socially, but he was also a lover of the city of Valencia, where he was born on 9 September 1911 in Calle de l’Almoina. In 1971, his candidature for the post of chronicler of the Valencian capital was rejected by 10 votes in favour and 15 against by the councillors of the pro-Franco City Council. In December 1978, this good man, of culture and dialogue, to whom the city of Valencia owes so much, received a parcel bomb at his home from far-right and anti-Catalanist groups which, fortunately, did not explode. His work on Valencia survives as an essential piece in the knowledge of the past and the urban geography of the Valencian capital.