In August 1917 Valencian newspapers echoed a case of severe poisoning associated to the food served in the restaurant Miramar of the Grau of Valencia. Among those affected, the most serious case was that of Julia Alonso Marzal, natural of Xàtiva, who had moved to Valencia on her honeymoon and died as a consequence of the foods ingested that day in the restaurant. Doctors who attended those poisoned report the case before the judge of the district of the Valencia market and then activated a series of procedures to determine the exact cause of the poisoning.

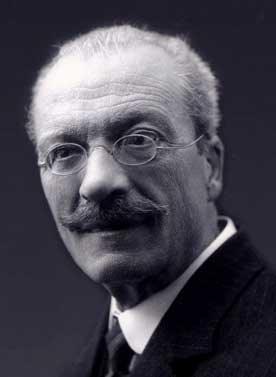

Despite the notoriety of the case, which became apparent with significant media coverage, and the fact that a large number of experts and institutions were involved in it, there was no consensus about the origin of the poisoning until two years later. Vicent Peset Cervera, on behalf of the Royal Medical Academy of Valencia, would be responsible for the preparation of the report that closed the controversy. His intervention was then conclusive, but it is more than evident that it was not the first time that the preeminence of the Valencian scholar became visible, whether in the field of food regulation or in other matters of medical and scientific practice. In fact, in the same episode of severe poisoning, the shadow of Peset was noted long before he took part as an academic of the Royal Academy of Medicine. We will briefly portray and contextualise this author and we will be able to better understand how the case of the death of Julia Alonso Marzal was developed and resolved.

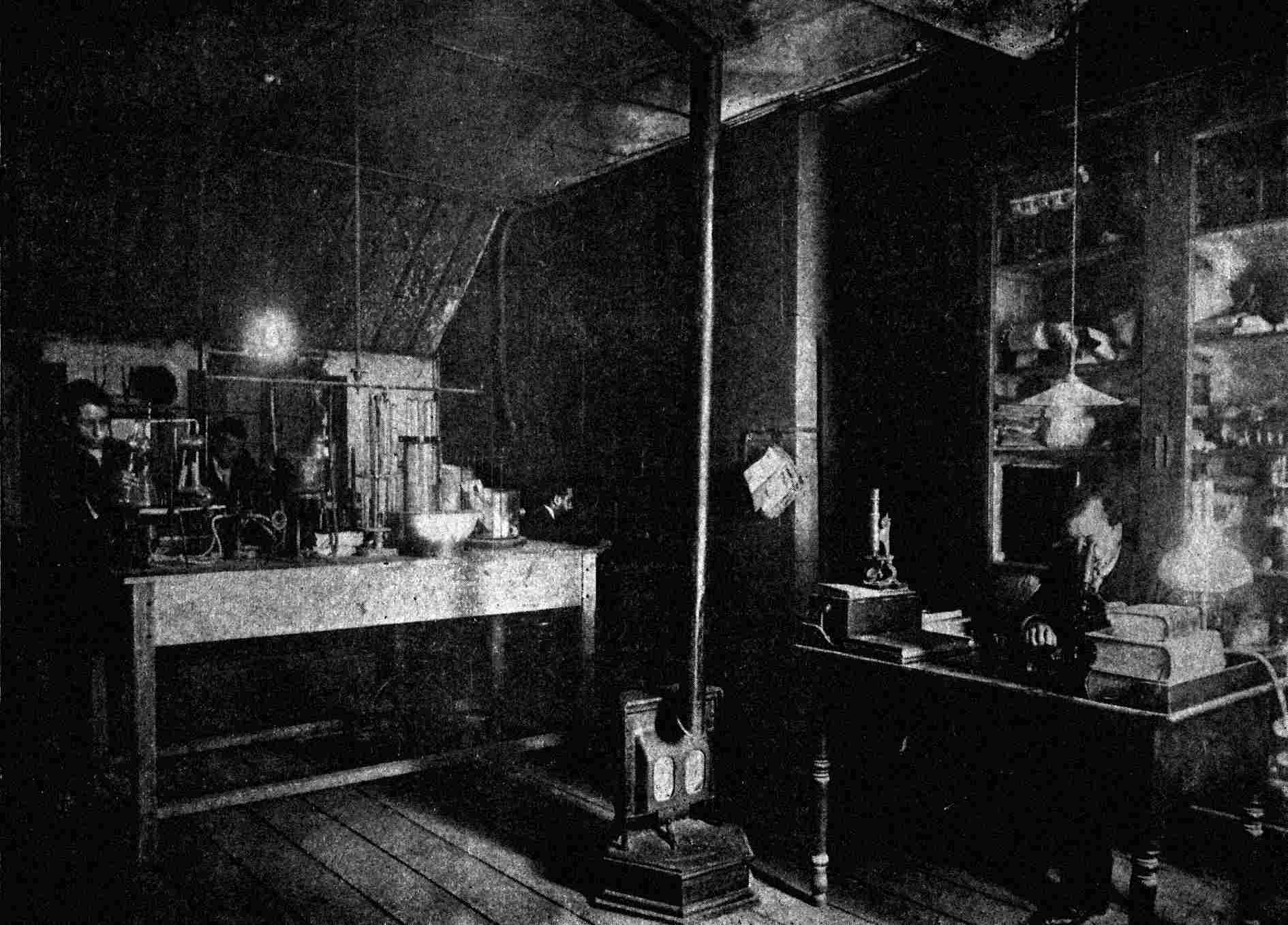

Vicent Peset Cervera was born in Valencia on April 8, 1855 and obtained a degree in medicine and surgery in 1874. A year later he obtained the doctorate degree in medicine and in 1879 he obtained a doctorate in physicochemical sciences. Soon after, he participated in one of the most important initiatives establishing a new Valencian service of food frauds repression: the creation of the municipal chemical laboratory of the capital. The laboratory opened its doors in 1881 and Peset Cervera obtained the municipal chemistry chair. In spite of not officially directing the laboratory, for practical purposes, he was its visible face from the start, with the elaboration of the laboratory project, as well as when publishing the activity reports and, apparently, performing a good deal of the analyses.

With the creation of the laboratory, Valencia moved towards a redefinition of food quality from its chemical composition and was placed in a good position in the transition to the establishment of the new services of repression of fraud. Brussels, Paris, Barcelona and Madrid, among others, had created or reactivated their respective municipal laboratories between the end of the 1870s and the beginnings of the 1880s, and Valencia would not be left out of it. Food fraud was then one of the main concerns, from a commercial as well as public health point of view, and Peset Cervera would be a key element in addressing this issue in the city of Valencia and its surroundings.

He remained in the municipal laboratory until 1888, when a law passed by Canalejas made the charge of municipal chemistry incompatible with the auxiliary professor’s position that he held at the Faculty of Medicine of the University of Valencia. In November of the previous year, he had been designated by a Royal Order chief of the Central Laboratory of Legal Medicine. However, it seems that he never occupied this place and renounced due to his “love for Valencia”. This same “love” made him resign other very attractive professional offers such as that made by the prominent Catalan physician and bacteriologist Jaume Ferran i Clua to join his laboratory or even the offer of a chair in Barcelona and Madrid.

After Peset Cervera left the municipal laboratory, it continued to be a fundamental tool in the fight against food adulteration. For example, in the case of the poisoning of the Miramar restaurant, the laboratory made an important contribution to the analysis of the seafood served there. Specifically, the municipal bacteriological laboratory (created in the 1890s as an independent laboratory of the chemical laboratory, but physically and organically clearly linked to it) established that poisoning could not be the result of ptomaine, typhus or paratifus, as it was common in the case of poisoning due to consumption of seafood in poor condition. However, laboratory director, José Pérez Fuster, said that in the analysis of seafood they had identified the presence of a bacillus that could give fevers of up to 41ºC and that therefore could not be dismissed that it was not involved in the death of Julia Alonso.

That report was one of those that Peset Cervera considered in his contribution to find out the causes of the decease. Therefore, the municipal laboratory was a source of knowledge recognized in the second decade of the nineteenth century. However, it is paradigmatic that the first reaction of the daily press when it began to inform about the case was to point to the possible analysis that would be carried out in the private laboratory of the Peset family. Vicent Peset Cervera had created the family laboratory in 1888, just when he vacated his position as a municipal chemist. In it, his sons Joan Baptista and Tomàs, as well as his brother-in-law Francesc Aleixandre, collaborated, and in the thirty years of the laboratory they carried out more than sixty thousand clinical analyses (including analyses of potentially adulterated foods and especially water). The press was well aware of the authority of this private laboratory, and both El Mercantil Valenciano and Las Provincias considered that this should be the most likely destination of the gastric juices and vesicles of the deceased. Finally, they went to the municipal laboratory, first of all, and at the Central Laboratory of Legal Medicine (in Madrid), later. But this confusion is more than significant in both newspapers.

And how is it that the press pointed to the Peset family laboratory? Well most probably because this was the process that had been followed on other occasions. Although it may be surprising, the Valencian courts sent samples of food to this private laboratory when the municipal laboratory of Valencia was already in full operation. For example, we know that on November 20, 1906, Peset Cervera made a report on the quality of a sample of lemonade that had reached its private laboratory. The sample was sent to the Serrans Court, and in the analysis, Peset verified that it did not contain saccharin, that drinking water had been used in the preparation and, therefore, despite containing too much lime essence, it had to be considered suitable for consumption. The Peset family private laboratory was in that case doing and charging the work that, in principle, the municipal chemical laboratory should have done for free.

One year before a similar episode occurred. In this case, however, samples of lemonade came from the court of Sant Vicent and in them Peset Cervera checked whether they contained saccharin and the quality of the water that had been used. Again the private laboratory of the Peset family replaced the municipal laboratory. We also know that this laboratory not only supplanted the public institutions, but also collaborated in food control. This became clear, for example, when it undertook a study on raisins in collaboration with the Provincial Institute of Hygiene. On September 11, 1922, that study was reflected in a manuscript that concerned the benefits derived from the consumption of raisins and that it was signed by both centres. The study had been carried out at the request of the Valencian agro-alimentary company SA Cornelli. This collaboration took place, precisely a year after Joan Baptista Peset Aleixandre took over the direction of the Institute, after the death of Torres Balbí.

Vicent Peset Cervera acquired a large local projection as an authority in various subjects, but in a very significant way in relation to food analysis and the repression of food fraud. That led to him being required by the courts to analyse samples related to a possible case of fraud or poisoning, or to intervene as an expert in the oral hearing of various trials. Although Peset Cervera abandoned its municipal chemical activity in the late 1880s, the authority he had acquired in this matter did not vanish. He continued to contribute to the suppression of food fraud occasionally, both through the channels we have just cited and as an expert in the contradictory analyses, a procedure that was then introduced to solve the conflict that could be raised between the municipal laboratory and the accused of fraud. In several documented cases, at the beginning of the second decade of the twentieth century, Peset Cervera was able to demonstrate to what extent he had an authority superior to that of the municipal chemical laboratory. He did it with his participation in contradictory analyses that ended up rejecting the conclusions of the laboratory.

He acquired that authority through the experiences we have already mentioned, but also through his dissemination and research activity. Related to his research work, it must first be said that he made contributions in very diverse areas such as food technology (with the development of a new method of peanut oil treatment), nutrition (with the analysis of the nutritional power of Bayer’s somatose, Wirke’s tropon, the liquid meats and other foods for the sick), agriculture (experimenting with methods to end the red poll), the pharmacy (discovering a active principle that was later known as podophyllotoxin), etc. One of the most significant contributions was done in X-ray experimentation. He was one of the first authors to participate in these investigations. Already at the beginning of 1896 he obtained some first X-rays in Godella, a municipality where he lived and where his was intimately bound. While in 1898, at the International Congress of Hygiene and Demography that took place in Madrid, he presented a communication dealing with the possible application of this technique in the detection of adulterations. The investigations that were made on certain foods such as wines, raisins and meat were also remarkable.

His status as a scientific expert gave him a great deal of prominence in the detection of food fraud in that context of transition that made obsolete controls based on organoleptic analysis and consolidated those that were based on chemical analysis. In the poisoning of the Miramar restaurant, all these factors we mentioned have had a very high specific weight when it comes to attributing a leading role in the resolution of the case. And yet, it must be taken into account that on that occasion, as in many others, “profane” knowledge, that was not backed with credentials, was really decisive. The various scientific experts consulted were unable to reach a consensus on the direct cause of intoxication. The reports that Peset Cervera had in his study for the Royal Academy pointed to very different causes. Some were inclined to consider seafood responsible, while others saw the origin of intoxication in the mushrooms consumed with meat. It was finally a Valencian chef, consulted by the Academy, who gave the key information that both courts and media who were carefully following the case were looking for. The cook explained the process to prepare the sauce and the mechanism used by many cooks to conserve it for prolonged periods. This process was very imperfect and could easily alter the product. Finally, a couple of years after the ill-fated episode of intoxication, what the chemical analysis and the knowledge of chemical experts, doctors and veterinarians could not resolve, was responded by the artisan and organoleptic knowledge of the cook.

The path to controlling the quality and safety of food based on chemistry would not be questioned at any time, but episodes like this showed its limitations. Of them, we would also be aware of Peset Cervera, which is why in its analysis of products, such as wines, it also resorted to the organoleptic analysis. Perhaps, however, it lacked a concrete proposal to systematically incorporate in the decision-making and in the inspections those who were experts in this organoleptic knowledge.

Beyond that case of intoxication that has allowed us to highlight some of the most relevant contributions and aspects of Vicent Peset Cervera, we can say that he was very active in fields such as teaching and communication. It is necessary to emphasise his contribution as a teacher (first as assistant professor of the Faculty of Medicine and then, from 1892 onwards, as a professor of therapeutics) and as a lecturer (both in academic and professional fields and in some of them more ideologically marked but with a very diverse sign). He was also a member of the main local medical and scientific societies (such as the Valencian Medical Institute and the Academy of Medicine mentioned above) and held various institutional positions (such as subdelegate of medicine in the Mar district, member of the Provincial Health Board or of the Sanitary Board of the Teatre district). We can thus highlight the strong integration of Vicent Peset Cervera in the Valencian scientific and medical context. But this integration in the local context cannot be fully understood as a result of its individual action, but in this sense it must be noted that it belongs to a group of liberal professionals that are very influential in the local area, such as the Peset family.

He was the son of the doctor Joan Baptista Peset i Vidal (author, among other works, of the medical topography of Valencia) and father of renowned professionals such as Joan Baptista Peset Aleixandre and Tomàs Peset Aleixandre, with whom he closely collaborated both in the Family laboratory and in the various institutional spaces they occupied. Most likely, this author’s local projection was greatly enhanced by this family network linked to academic and institutional power. But it is also true that his influence exceeded the local, Valencian limits, and was very active both in the dissemination and research in a field of state scope (often collaborating in publications of Ciudad Real, Madrid, Zaragoza, Teruel, etc.)

It is also true that his contributions were usually linked to his medical and scientific activity. And in this sense, a biographical account published in Medicina Valenciana in January 1918 came to suggest that “he always preferred the serene calm of the Laboratory; He only worried about scientific issues, fleeing the controversial sterile in use”. But these images, easily criticized, of the scientist isolated or independent from the society that surrounds him were not new and have not ceased to be habitual today, at least in certain contexts. In the case of Peset Cervera, we can deny this image if, for example, we briefly comment on one of its most influential public works, its booklet Lo que debe a España la cultura mundial (‘What world culture owes to Spain’).

In 1925, on his 70th birthday, the forced retirement of Peset Cervera arrived, but the sources show that he remained active in very different forms. For example, he did it with his classes of critical medical history, and it seems that in the preparation of these classes he collected the necessary materials to write the booklet that we referred to. The book showed a tone of exalted Spanish patriotism. Its starting point was the inaugural lecture of the 1924-1925 academic year at the University. Its title is more than just illustrative: AMEMUS PATRIAM! (La influencia española en la cultura mundial) (‘The Spanish influence in world culture’). And Peset Cervera would say of it that the theme was inspired by “patriotism, something decayed at the time”, and that prepared it “to awaken, in a word, a lively patriotic sentiment in the crowd...”. This goal made him state, for example, that “Spain founded the sixth part of Universities of the world”, that “Spanish imperialism was [the] most glorious of Europe then”, that the chemical war was a Spanish invention, etc. The text was, in fact, all but the work of the apolitical scientist who said that identified in Peset Cervera the article on Valencian Medicine that we have referred to earlier. Moreover, if, as Peset Cervera indicated, it reflected the contents of his course of critical medical history, we could hardly understand that this subject included the word “critical” in its name. Certainly, if we compare his political commitment to that of his son Joan Baptista, we could say that this was not particularly relevant, but that more political and ideological world was not strange for Peset Cervera.

After retirement, with more or less political or scientific works and various contributions, both individually and in co-authorship with his son Joan Baptista, Peset Cervera remained intellectually active until his death in 1945.

Ximo Guillem-Llobat

“López Piñero” Institute of History of Medicine and Science – Universitat de València

To know more:

Rodríguez, P.; Torres, R. C.; Sicluna, M. I. (eds.), Juan Peset Aleixandre. Médico, Rector y político republicano. Madrid, Eneida, 2011

Guillem-Llobat, X. De la cuina a la fàbrica. L’aliment industrial i el frau. El cas valencià en el context internacional (1878-1936). Alacant, Publicacions de la Universitat d’Alacant, 2010.

Personatges i espais de ciència (‘Science characters and spaces’) is a project of the Unit of Scientific Culture and Innovation of the University of Valencia, with the collaboration of the “López Piñero” Institute of History of Medicine and Science and with the support of the Spanish Foundation for Science and Technology and of the Ministry of Economy, Industry and Competitiveness.

.jpg)