It should be said first of all: right now Rafael Vilar Fiol (1885-1971) is someone quite unknown, largely as a consequence of exile in France as a result of the Civil War. From 1939, he lived in Paris, where he died without having seen the end of Franco’s dictatorship. He certainly and occasionally returned when he was in his eighties but the destination was not Valencia, but Madrid. The data we have gathered still reflect a partial and fragmentary figure, located in unconnected and successive scenarios, which include activities, institutions and very different locations.

He is, in addition, a difficult character to fit in a standard classification. In fact, it is not easy to know what was the main aspect of his long scientific and professional career. From a myopic vision, it would be tempting –as well as impoverishing– to reduce his biography to one of the disciplines or specialties that he cultivated over the years: dentistry, otolaryngology, and stomatology or, already retired, comparative and phylogenetic anatomy. However, we can affirm that his scientific interests revolved around the oral apparatus and by extension the whole oronasopharyngeal territory. He was interested both in the morphological and physiological aspects as well as in the pathological, diagnostic and therapeutic ones, including the surgical and pharmacological ones.

In this line, we should emphasise the contributions to the anatomical knowledge of nasal and paranasal sinuses and, in particular, to the evolutionary configuration of the ethmoid bone and its significance in the verticalisation of the skull in the human species. However, we cannot forget that, as a professional, Vilar Fiol was a doctor who had open consultations to the public, according to the yearbooks of the Boletín de la Unión Sanitaria Valenciana (‘Valencian Health Union Bulletin’) (1920-1936). From 1922 to 1936 Vilar Fiol served as an

odontologist and otolaryngologist successively in Drets, Pintor Sorolla, Governador Vell and Ambassador Vic streets, of the city of Valencia. Later on, we will see that in Paris, he worked as an otolaryngologist, first at the Prophylactic Institute of the Pasteur Institute (1940-1947) and after that at the Cervantes Dispensary of the Spanish Republican Red Cross (1948-1954).

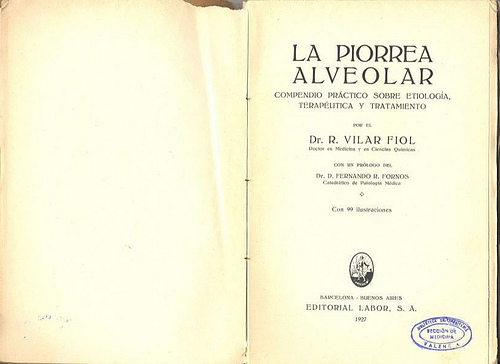

Born in Gilet (the Camp de Morvedre) in 1885, Rafael Vilar Fiol obtained, in July 1906, therefore very young, a degree in Sciences (Chemistry section) by the University of Valencia. Three years later, the newspaper Las Provincias welcomed his achievement of the degree of doctor. In parallel, still a student of science, he had begun in 1903 the Medicine degree, studies that he left temporarily in 1910 when he had already passed the first three years. Then, Vilar Fiol decided to move to Madrid, perhaps influenced by his father –Antonio Vilar Ridaura–, a certified surgeon and dentist from Alcoi. At the Madrilenian Dentistry School, he passed Dentistry and Dental Prosthetics, two subjects that, along with the first three courses of medicine already passed, allowed him to obtain the degree in Odontology in 1911. With these credentials he moved to Paris and Berlin, where he deepened in the study of oral infections –especially the alveolar pyorrhea– under the direction of the best specialists of the time. In Paris, he trained with the prestigious Cuban dental practitioner Óscar Amoedo (1863-1945), who was a professor at the École Odontotechnique and an expert in legal dentistry.

In 1924, he exhibited his casuistry, accumulated for more than ten years of professional practice, at the National Congress of Dentistry, held in Seville. He then resumed his medical studies in Valencia and obtained a bachelor’s degree in May 1927. In July of the following year he obtained a doctorate degree in Medicine in Madrid with a thesis on oral infections, which included his experience as a dentist. At that time, he attended international congresses, both those of dentistry and stomatology and those of otolaryngology, preferably from the French-speaking area. In fact, French was the vehicular language of his scientific work, although he also published in Spanish and, in some cases, in German.

In Valencia, Rafael Vilar Fiol had a close relationship with the Instituto Médico Valenciano (IMV) (‘Valencian Medical Institute’), the dean of the city’s medical associations. Thus, in February 1927 –soon, therefore, to conclude the studies of medicine– he gave a lecture on mouth cancer. The press then referred to him as “the eminent and doctor odontologist Rafael Vilar Fiol”, despite not having finished his degree. And the press was right, because he was a doctor in Sciences.

The following year, 1928, he was awarded by the IMV the honorary member title for his work «Seno maxilar en relación al sigmoides y al seno frontal» (‘Maxillary sinus in relation to sigmoids and frontal sinus’), a work that would be immediately translated into French. Vilar Fiol described for the first time a canal that communicates the maxillary sinus with the ethmoidal and frontal sinuses. This conduit has been internationally known since then as Vilar Fiol fosette, one of the few anatomical Spanish eponyms of the twentieth century. In 1929 he worked with the IMV again, but this time sharing the road with Fernando Rodríguez Fornos (1883-1951), Professor of Medical Pathology at the University of Valencia. The coauthorship of the conference was not debated, since the topic revolved around the relationship between oral infections and internal medicine. On this occasion, Vilar Fiol presented the new technique for the treatment of oral infections recommended by colleague and friend Alexandre Besredka (1870-1940), a renowned immunologist at the Pasteur Institute in Paris. It should be noted that Alexander Fleming (1881-1955) was strongly interested in the bacterial studies of Besredka related to the then so-called “antivirus”, that is, cultures of bacteria capable of producing local immunity.

In 1927 Vilar Fiol began his academic career as assistant professor of the subject Anatomical Technique at the Faculty of Medicine of Valencia. The enactment of the Callejo Law, which allowed the provision of new medical chairs, offered him the opportunity to occupy a position of professor of Dentistry and to consider the possibility of founding a dental school in Valencia at the Faculty of Medicine.

With the advent of the Republic in April 1931, Vilar Fiol led the project to found a dental school in Valencia, whose initiative came from the students of the Faculty of Medicine organised around the Professional Association of Dental Students of Valencia. This association was integrated in the School University Federation and was presided over by the student Cayo de Basterra.

At that time, the only centre in the whole State with competencies to grant the title of dentist was the School of Dentistry of Madrid, which forced a large number of Valencian students to go there. This idea had the determined support of the University, the Provincial Council and the City Council of Valencia, which provided resources of all kinds, human and material. Even the Valencia Conservative Press applauded the initiative of Vilar Fiol. Finally, in April 1932, the Ministry of Public Instruction and Fine Arts issued a resolution contrary to the proposal, and the project was irrevocably rejected. In the ministerial resolution we weighed the pressure of the Madrid school, which did not have any interest in losing students, but also that of dentists’ colleges, both the one of Madrid and the one of Valencia, who feared an excessive increase of the number of professionals. If it had been approved, the Valencian school would have had premises, annexed to the Provincial Hospital and the Faculty of Medicine, with their own entrance on Quevedo Street, in the immediate vicinity of Guillem de Castro Street.

Having definitely abandoned the dental school project, Vilar Fiol opted for other channels of action in the public sphere. On the one hand, he entered politics, an activity that, for him, was always linked to the field of health; and, on the other, he chose to go in for a public competition and get an official job. Indeed, in March 1933 he won the otolaryngologist position at the Fontilles Sanatorium (Marina Alta), a centre specialised in fighting leprosy. And, when the war broke out, he acquired an important role in the management of Valencian health; in particular, he held the position of general secretary of the revolutionary People’s Health Committee, which did not prevent him from being appointed director of the aforementioned sanatorium in October 1936.

As for his political and trade union activity, in 1932 Vilar Fiol was elected as the Valencian Socialist Federation spokesperson. Also during the years of the Republic he founded and promoted the Medical Union of the UGT in Valencia and its province, where he held different positions: secretary and provincial president and delegate in the National Committee. It should be remembered that the UGT Medical Union had been founded by health expert Marcelino Pascua (1897-1977), a figure of renowned international prestige and the first Health general director of the Republic. During this stage, Vilar Fiol actively participated in the debate on social welfare and maternity insurance, acting as an intermediary between the Medical Union and the health officials of the Government. However, his political concerns led him to participate, sometimes, in informative debates, and thus we find his name among the speakers of the symposium organised in 1932 by the Ateneu de Burjassot under the title Science and politics. All this explains that, at the end of the war, Vilar Fiol had been forced to exile, and that, in those circumstances, France was the preferred destination.

We have not found any indication of the path followed by Vilar Fiol in moving to France after the Republican defeat of 1939. Perhaps, like so many Valencians, he went first to Algiers and from there he reached the Metropolitan France; or maybe he knew the bitter experience of concentration camps. However, we know that in September of that same year –the year of catastrophes, as it was very correctly called –, he was already working at the anti-tuberculous sanatorium of Dreux, a town close to Paris between Normandy and the Ile de France, and that shortly after he joined the faculty of the Institut Prophylactique of the Pasteur Institute, located at number 36 of the Assas Street, where he worked as an otolaryngologist until 1947. The reports of Franco spies say that he achieved it thanks to his links to masonry, although they point out that he was not a mason. However, they do not mention that as a scientist he had had close relationships with his French colleagues, including Alexandre Besredka, head of the Prophylactique Institute, who had distinguished himself since 1933 to host many Jewish German scientists that fled from the anti-Semitic laws implanted by Hitler and his supporters in Central European countries.

In Paris, Vilar Fiol published a book, entitled L’homme et le milieu social (Alcan, 1940), whose writing had begun in Valencia. He finished writing it just weeks before the outbreak of World War II, a war, according to him, between civilisation and barbarism. Banned during Nazi occupation, the book was severely criticised shortly after the liberation of France in La Pensée, the prestigious French magazine related to “modern rationalism”. From Marxist positions, Jean Kanapa (1921-1976) attacked him relentlessly because he considered it, besides pretentious, an approach lacking “sociological method” and excessive moralising eagerness.

In 1947, when the Valencian Regional House was constituted in Paris, Vilar Fiol was appointed a member of the first board of directors. The House was a moderately Valencian entity chaired by Josep Castanyer i Fons (1900-1951), which emerged as part of the Republican exile. Vilar Fiol was entrusted with the spokesperson position of Social Welfare, probably in recognition of his medical dedication to Spanish refugees at the Prophylactic Institute of the Pasteur Institute under the protection of the Red Cross. Indeed, Vilar Fiol had been named “health delegate”, for Paris, of the Central Committee of the Red Cross of the Spanish Republic, which had been (re) constituted in Toulouse in the spring of 1945 under the presidency of Josep Martí Feced (1890-1963), former leader of the Red Cross in Catalonia. Indeed, Vilar Fiol had been named “health delegate”, for Paris, of the Central Committee of the Red Cross of the Spanish Republic, which had been (re) constituted in Toulouse in the spring of 1945 under the presidency of Josep Martí Feced (1890-1963), former leader of the Red Cross in Catalonia.

Significantly, at the beginning the Paris delegation of the Red Cross had the headquarters in the aforementioned Prophylactic Institute and, in particular, at the services of the Otorhinolaryngology Service where Vilar Fiol worked. With the consent of the International Committee of the Red Cross (CIRC) in the distance and the direct protection of the French Red Cross, the Red Cross of the Spanish Republic, as studied by Alicia Alted, created a network of dispensaries located in Several French cities, in order to provide health and social assistance to the thousands of Spanish refugees. Meanwhile, Franco’s military regime managed to stay in power thanks to the support of the United Kingdom and the United States in the Cold War. Doctors, dentists, nurses and Spanish practitioners, also exiled as their patients, worked at the Red Cross clinics with the approval of the French Government. Billoux Law, 1945, allowed foreign health workers to assist their compatriots in centres that provided humanitarian aid, which implied, despite the marked limits, an implicit recognition of their academic and professional qualifications. This is how the Warsaw Hospital of Toulouse was born, a healthcare centre that today receives the name of Hôpital Joseph Ducuing. The Spanish Republican Red Cross took root in the populations where there were colonies of Spanish refugees. Very weakened after Franco’s death due to the return of the exiles and the lack of resources, it definitively disappeared in 1986 with the entry of Spain into the European Union.

From a scientific point of view, the most interesting chapter of the biography of Vilar Fiol is without a doubt the one comprised of his studies on the configuration of the nasal and paranasal sinuses and, more exactly, the process of increasing pneumatisation that these structures experience in the evolutionary process of the upper mammals. The discovery of the canal that communicates the maxillary sinuses with the frontals through the ethmoid goes back to 1928, as we have seen above. It was not a simple anatomical curiosity, since this finding would have important repercussions to understand the pathogenesis of sinusitis and to adopt more effective therapeutic strategies. Jean Terracol (1883-1972), otolaryngology professor at the University of Montpellier, warned him at the beginning of the 1930s and attributed to Vilar Fiol the discovery of the aforementioned nasal fossette. Years later, in 1965, Terracol recognised the debt he had contracted with Vilar Fiol and shared the authorship of the monograph titled Anatomie des fosses nasales et des cavités annexes, which the following year received the Prix Orfila of the Académie Nationale de Médecine of Paris.

In the 1950s, more or less coinciding with his retirement, Vilar Fiol volunteered as researcher at the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle in Paris, specifically at the Comparative Anatomy Laboratory directed by Jean Anthony (1915-2004). This link allowed him to continue his studies on nasal and paranasal sinuses for almost two decades and study, in particular, the comparative anatomy of the ethmoid bone. He was interested in the role of pneumatisation of the skull in the verticalisation of the upper mammals, one of the most exciting episodes of evolution and, in particular, in the hominisation process, a line of research that Vilar Fiol had begun in Valencia that then, in Paris, emerged again. Consequently, he contributed without trying to confirm the existence of a Valencian tradition of scientists advocate of evolutionary thinking in biology, such as Anatomy professor Pelegrí Casanova Ciurana (1849-1919) and students grouped in the Medical and Scholar academy that organised in 1909 the tribute to Charles Darwin.

In December 1969, more than eighty years old, Vilar Fiol contacted the Department of Paleontology of the Complutense University of Madrid, invited by the director, Bermudo Meléndez (1912-1999). A few months later, on April 9, 1970, he participated in one of the Paleontology Colloquies, whose acts were later published in the CO-PAL magazine. His intervention focused on cranial pneumatisation as a key in the process of verticalisation in the evolution of mammals. It was probably his last public appearance, because he died a year later.

As we said at the beginning, Vilar Fiol was born in 1885 in Gilet (Camp de Morvedre). However, no street in his town, nor in the city of Valencia, is named after him. There is no trace, in the collective memory, of a character who tried to found a stomatology school in Valencia during the Republic, who directed the Fontilles Sanatorium during the Civil War, who worked as an otolaryngologist in the Pasteur Institute of Paris under the Nazi yoke, who reorganized the Republican Red Cross after the Liberation of France and, already retired, collaborated as a volunteer researcher with the tasks of the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle in Paris. His invisibility is such that, despite the biographical research carried out, his portrait has been found only with very low quality conditions. 2021 will be the fiftieth anniversary of his death. It would be a good time to historically analyse the polyhedral figure of Vilar Fiol in all its complexity, freeing it from oblivion.

Àlvar Martínez Vidal (“López Piñero” Institute of History of Medicine and Science / Universitat de València)

Xavier Garcia Ferrandis (Universidad Católica de Valencia)

Personatges i espais de ciència (‘Science characters and spaces’) is a project of the Unit of Scientific Culture and Innovation of the University of Valencia, with the collaboration of the “López Piñero” Institute of History of Medicine and Science and with the support of the Spanish Foundation for Science and Technology and of the Ministry of Economy, Industry and Competitiveness.