Pests have been a recurring problem in the long history of agriculture. But from the last decades of the nineteenth century its impact acquired totally unknown dimensions until then. The intense transformation experienced by the food system from the 1870s led to the redefinition of agriculture in order to move towards more mechanised, intensive and monoculture-based models. In this sense, for example, the theoretical contributions made by authors such as Albrecht Daniel Thaer or Justus von Liebig during the first half of the nineteenth century, and the subsequent expansion of the food chain, were fundamental in order to promote a change towards export agriculture. And with it, the damages caused by pests were greatly aggravated.

In this context, the previously applied pest controls (often physical controls) were no longer enough. Scientists and producers had to look for new control methods and to do so they often went towards the development of both chemical and biological controls. In the Valencian Country, in order to develop and implement these methods, the Burjassot Plant Pathology Station was created at the beginning of the twentieth century.

Abans, però, en les últimes dècades del segle XIX, tant en el context valencià com en l’internacional, s’hi van promoure tota una sèrie d’institucions, i a la fi, d’espais, per impulsar la transformació de l’agricultura a què ens referíem adés. La creació de l’Estació de Patologia Vegetal de Burjassot no es pot entendre fora d’aquell context i de les iniciatives que ara comentarem breument.

However, before the last decades of the nineteenth century, both in the Valencian and the international context, a whole series of institutions were promoted, and in the end, spaces, to boost the transformation of the agriculture that we earlier referred to. The creation of the Burjassot Plant Pathology Station cannot be understood outside of that context and the initiatives that we will now briefly comment.

Undoubtedly, one of the main spaces to promote change were the agronomic stations or experimental agricultural stations. Often reference is made to the Möckern station (Saxony) as the first of these with public funding. That station could have represented a model for those that would soon be created. Only in Europe, it is estimated that in 1868 around 40 stations already existed; many of which had been created in the Germanic domain. In order to present the project of the Möckern station, some of its promoters already made explicit reference to the influence that had been carried out by Thaer, who was “founder” of a new system of “rational” agriculture, and hero among German landowners for having promoted the increase in productivity through comparative studies. However, Thaer was sceptical enough regarding the practical interest of what we could call basic research.

On the other hand, there are few historians who have linked the establishment of these stations to the strong influence exerted by Liebig’s work in the world of agriculture. However, Liebig’s discourse (not necessarily its practice) emphasised basic research, and it seems that this was not the main task of these first stations. From their origin, these stations were spaces with a hybrid project that tried to build bridges between laboratory science and agricultural practice. In this regard, one of the promoters of the Möckern station, professor of agricultural chemistry, Julius Adolf Stöckhardt, said that “we learn more in the taverns than in conference rooms and churches”.

The German stations, such as their universities or laboratories, were a very influential model in the institutionalisation of science in the US. However, in the Iberian context these initiatives would often come through reflections or initiatives promoted in third countries, and specifically in France. But the French influence became especially visible in relation to the creation of another set of spaces (or institutions) that significantly contributed to the transformation of agricultural practice: experimental farm schools. Unlike the previous ones, these spaces were characterised to include teachers among their tasks, with training at different levels.

In Spain, since the beginning of the nineteenth century several structures had been promoted to boost agricultural development. Initiatives such as the boards of commerce, economic societies or the subsequent provincial agricultural boards were along this line. On the other hand, in parallel or a little later, several farm-model and agricultural schools were created, strongly influenced by the French experience. In Valencia, these initiatives led to the creation of the Model Farm of Valencia, which from 1887 begun to be called Experimental Farm School of Valencia and which was renamed on several occasions after that. Historians such as Jordi Cartañà have suggested that the 1887 change would not be solely nominal but would lead to more substantial changes caused by the failure of the previous pattern of model farms.

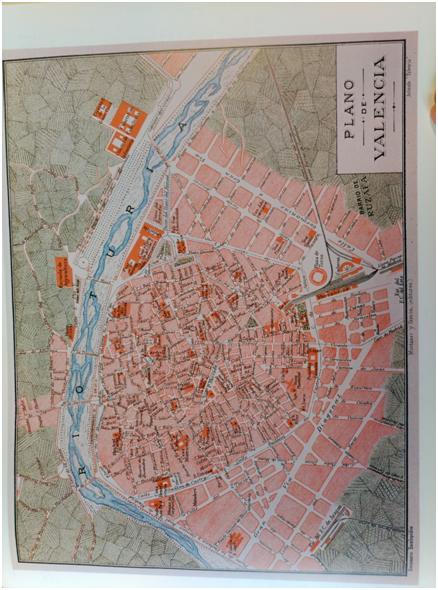

Back then the need to create a centre such as the Plant Pathology Station had yet not been considered, but it is advisable to keep in mind all these previous initiatives, since it is within these that the station was subsequently created which will occupy our following paragraphs. In this regard, it is also necessary to make a brief reference to the location in which that model farm was created. In 1868, the Acclimatisation Garden had already been created in the Royal Garden of Valencia (outside of which were the walls, just across the river). Subsequently, in this same location the Model Farm and the successive Experimental School Farm were created, the last of which remained in this place until 1892, when it moved to Burjassot.

Source: https://burjasothistorico.blogspot.com/ Arturo Cervellera

Most likely this change of location could be understood, among other things, in the context of the expansion of the urban centre of Valencia. As Manuel Sanchis Guarner reminded us, with the demolition of the wall and the subsequent initiation of the Eixample (‘expansion district’), the aim was to take care of the old city-planning problem of connecting the nucleus of the city with the Grau (‘maritime district’). With the increase in the export and the development of port towns, it became more necessary to approach the sea and, with that objective, Valencia joined Vilanova del Grau and Poblenou de la Mar in 1897. In addition, in the expansion projects that Francesc Mora presented a few years later (who was the municipal architect of the Eixample during the first half of the twentieth century) the clear intention of urbanising the whole territory that could be observed and surrounded the Jardins del Real. In the expansion of the city towards the sea, agriculture had to disappear from the territories that surrounded the Experimental Farm School.

In this sense, the transfer of the Farm to Burjassot could be perceived as necessary, to have within reach the land required to perform its tasks. But, on the other hand, this change could also be justified based on the desire to maintain direct relationship with local farmers. In fact, as we shall discuss later, establishing a more direct and fluid relationship with farmers would be recurrently sought from the Experimental Farm School.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, both the Valencian and Spanish authorities became more aware of the problem generated by the country pests and promoted various initiatives to tackle them. The management of the Farm School had been run by both the state and the Provincial Council and it was within this centre where the reformulation of the fight against pests was more intensively promoted. On the state level, on May 21, 1908, the first plague law of the field was approved and a little over a year a RO was published that required the creation of a plant pathology annexed to the Farm School of Valencia. At that time there was only one station of this kind in Spain, in this case annexed to the Agricultural Institute Alfonso XII in Madrid. It was then assessed that another station was necessary and most likely the important damage that was already being generated then by the Spanish red scale on the orange economy were decisive in order to choose the location of the second station. But it seems that the 1909 station never worked autonomously and that in the end, the Farm School was responsible for promoting a more effective reaction against the pests.

On June 20, 1924, a new provision was approved for the reorganisation of agricultural services and in this royal decree, among other things, the need arose to create several plant pathology stations, among which the one in Valencia. Apparently this royal decree was positively received by the Valencian authorities and, unlike what happened with other proposed stations, the new centre soon became a reality. The RD already marked up to eleven tasks to be developed by the new stations that, as Salvador Zaragoza points out, in a synthetic way it would consist of: classifying and studying the plant and animal species that constitute pests, studying the prophylactic or defence procedures, trying techniques to tackle pests and investigate the indigenous or foreign entomophage species and breeding them in insects, creating a museum with pests and diseases common in the region, responding to the queries that they receive and disseminating their investigations results.

Cartografía histórica de la ciudad de Valencia, 1704-1910.

Valencia: Ayuntamiento de Valencia)

When in the 1890s, the Farm School

When in the 1890s, the Farm School of Valencia arrived at its new location in Burjassot, there was no project to create this plant pathology station and the space did not adjust then to the development of all these functions. In the 1920s, the space adaptation to its new functions was then peremptory, those derived from the creation of the new centre. But we must not forget that in those years there would still be new changes in the set of the Burjassot facilities. Thus, in 1931, the Farm School, which from 1924 was renamed as Horticulture and Gardening School Station, was closed so that the Oranges East Station was created in lieu thereof. Previously, other stations had already been stablished in towns such as Sueca and Requena to address the needs of other specific crops of special interest in the Valencian countryside, such as wine or rice. But, undoubtedly, the change in name and functions of the Burjassot facilities highlighted the hegemonic role that orange would develop from then on. In fact, the very existence of this space not only confirmed it but reinforced it.

The adaptation of the Burjassot facilities to the new functions that the Plant Pathology Station was to develop lead to the creation, in 1927, of an entomology laboratory, a cryptogamy laboratory, a therapeutic laboratory, a brood insectarium, a phytopathological museum and a library. Subsequently, these facilities would be reformed, such as through the new division of the centre’s experimentation fields, and new ones were added, such as the new brood insectarium in 1931. In some cases even new facilities were generated by intervening in other parts of the Valencian metropolitan area. For example, between 1935 and 1937 numerous works were performed in the port to create the Port Phytosanitary Station. Without a doubt, all of these facilities would be essential in order to develop both research on country pests and to improve the incidence of research in the Valencian field through the advice of professionals and the development of training courses such as for forepersons and on hydrocyanic acid fumigation. However, it must be said that inevitably this spatial evolution (with the creation of new facilities and the spatial coincidence of the orange and plant pathology) equally contributed to establish important knowledge about pests, and especially those that affected the orange tree, also created ignorance on all those crops that were left in a second plane or completely disappeared from the look of engineers associated to the centre.

When analysing the space tensions that have occurred in contemporary history in relation to the centres dedicated to the study of the natural world, one of the most interesting approaches is that posed by historian Robert Kohler when coining the term Labscape (hybrid word of “laboratory” and “landscape”). From the mid-nineteenth century, science began to dominate among life sciences. In this area, as in the rest, the laboratory was presented as the “placeless place” that was to be a guarantee that the knowledge produced in this space would have universal validity. However, in the case of life sciences, these laboratories were not free of controversy. As it had already happened with instruments like the microscope, it was considered whether the artificiality of the laboratory could not be an impediment to capture what really happened in the natural environment.

(Salvador Zaragoza Adriaensens (2011).

Origin and activities of the Valencian Institute for

Agricultural Research 1868-2000).

It was then tried to naturalise laboratories, from rhetoric as well as creating hybrid spaces that were half way between the “artificiality” of the traditional laboratory and the “naturalness” of natural spaces. Kohler has referred to the creation of these hybrids through spaces such as field laboratories and vivariums, established between the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. But as he says, agronomic stations (such as those considered in this article) are also a good example of these hybrid spaces. The laboratories of these stations could not isolate themselves from the insects and fields of experimentation. And so the continuity between natural and artificial environment, between field and laboratory, was assured. On the other hand, the need for this continuity was more obvious and less controversial in this case, since explicitly a local or localised knowledge was demanded before the usual universal knowledge of science. They knew that the particularities of each territory with their crops and their pests demanded the production of this local approach to knowledge. And they did so on numerous occasions.

The local particularities of each territory also depended on the skill and practices of the farmers with whom they wanted to establish a close relationship. As we have already mentioned, since the creation of the first experimental agricultural station, we find speeches that claim a kind of “construction” of knowledge, putting the wisdom of field workers in value. But it would be necessary to study the extent to which these speeches were transformed into specific initiatives. It would be necessary to find out in what terms the contact with the farmers was sought (encouraged in the case of Valencian stations through the aforementioned location changes). And, ultimately, it would be necessary to evaluate how the station was defined as a “contact zone”, a space for the circulation of knowledge between two a priori so different approximations to knowledge as those of agronomist engineers and farmers. These questions, like others, show the interest that studies of these stations can arouse from the perspective of the geographies of knowledge; an interest that should not be limited to understanding our history but also to build our future. In this case, this contribution will undoubtedly be able to redefine the current agronomic institutions so that they function as truly effective “contact areas”.

To know more:

Salvador Zaragoza Adriaensens (2011). Origen y actividades del Instituto Valenciano de Investigaciones Agrarias 1868-2000 (http://www.ivia.gva.es/libro-salvador-zaragoza)

Jesús Català Gorgues and Ximo Guillem Llobat (2006). Control de plagas y desarrollo institucional en la estación de Patología Vegetal de Burjassot (Valencia). Asclepio 58 (1): 249-280 (DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3989/asclepio.2006.v58.i1.8)

Ximo Guillem-Llobat

“López Piñero” Institute of History of Medicine and Science, University of Valencia

Personatges i espais de ciència (‘Science characters and spaces’) is a project of the Unit of Scientific Culture and Innovation of the University of Valencia, with the collaboration of the “López Piñero” Institute of History of Medicine and Science and with the support of the Spanish Foundation for Science and Technology and the Ministry of Economy, Industry and Competitiveness.