The University of Valencia participates in a research that shows Siberian Neanderthals enjoyed both plants and animals on the menu

- Scientific Culture and Innovation Unit

- June 8th, 2021

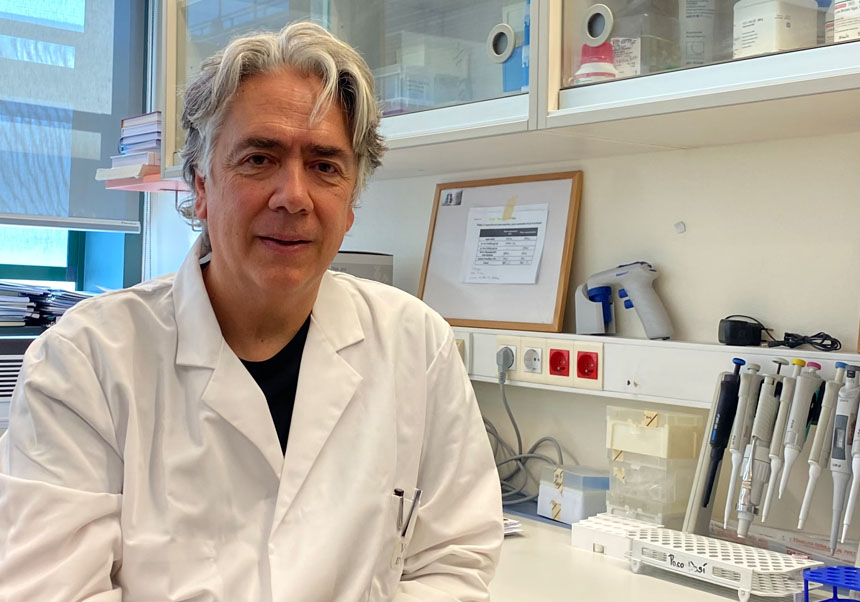

Neanderthals, extinct cousins of modern humans, occupied Western Eurasia before disappearing and although it was once thought that they ranged as far east as Uzbekistan, in recent years an international research team with the participation of the University of Valencia discovered that they reached two thousand kilometers further East, to the Altai Mountains of Siberia. An international research team led by Domingo Carlos Salazar, CIDEGENT researcher of excellence at the University of Valencia, published today in the Journal of Human Evolution the first attempt to document the diet of a Neanderthal through a unique combination of stable isotope analysis and identification of plant micro-remnants of an individual.

The analysis of Neanderthal bones and dental stones from Siberia sheds light on their dietary ecology, at the eastern limit of their expansion. It is a very dynamic region where Neanderthals also interacted with their enigmatic Asian cousins, the Denisovans. The work refers both to western Siberia, where there are studies that explain that modern humans responded with high mobility, and to the eastern part, where there is a lack of work that analyses the behaviour and subsistence of Neanderthals, who inhabited this Siberian forest steppe, which is drier and colder than the western one. Studying the diets of eastern Neanderthals allows us to understand their behaviours, mobility, and potential adaptability.

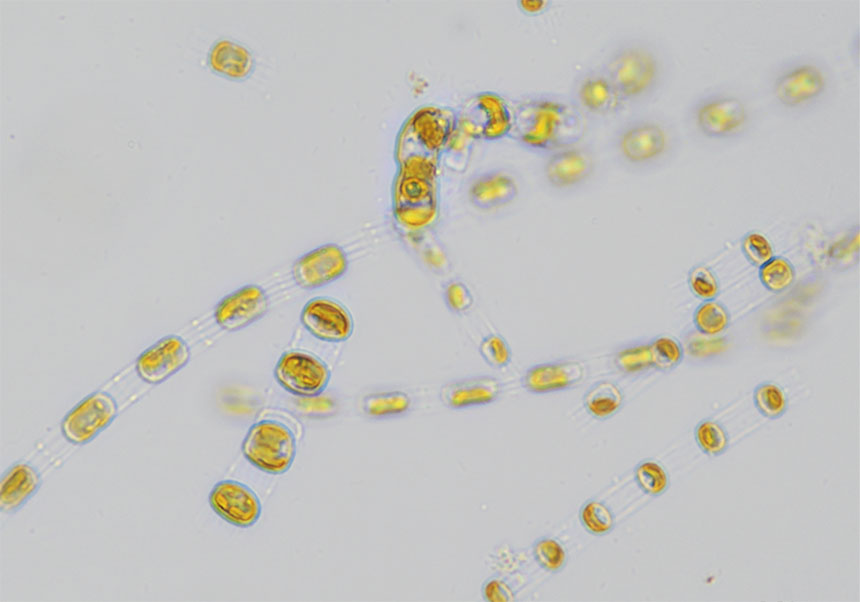

A team of researchers from Spain, Germany, Canada, The Netherlands and Russia, led by physician and historian Domingo Carlos Salazar García from the University of Valencia, took bone samples and dental calculus from Neanderthal remains dated to 60 and 50 ka BP from the site of Chagyrskaya in the Altai Mountains in Southern Siberia, located just 100 km from the Denisova Cave. Analyses of the stable carbon and nitrogen isotopes from one mandible (Chagyrskaya 6) revealed that this individual had a relatively high trophic level compared to the local food web, indicating that it consumed a large amount of animal protein from hunting large and medium-sized game. Using optical microscopy, the researchers identified a diverse assemblage of microscopic particles from plants preserved in the dental calculus from the same individuals as well as from others from the site. These plant microremains indicate that the inhabitants of Chagyrskaya also consumed a number of different plants.

These results can help us answer a long-standing enigma about the Altai Neanderthals: the region was tempting enough that Neanderthals colonised the area at least twice, but genetic data indicates they were barely hanging on, living only in small groups that were constantly at risk of extinction. The dietary data now indicates that this unusual habitation pattern was probably not due to a lack of adapting their diet to the local environment. Instead, other factors such as the climate or interaction with other hominins should be investigated in future studies.

“Even in adverse climatic environments Neanderthals were capable of having a diverse menu”, says Domingo C. Salazar García, “it was really surprising that these eastern Neanderthals had broadly similar subsistence patterns to those from Western Eurasia, showing the high adaptability of our cousins, and therefore suggesting that their dietary ecology was probably not a disadvantage when competing with anatomically modern humans”.

“These microremains provide some indication that even as Neanderthal expanded onto the vast and cold forest-steppe of Central Asia they retained patterns of plant use that could have been developed in Western Eurasia”, says Robert Power, researcher at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology.

Dietary ecology

“A better grasp of Neanderthal dietary ecology is not only the key to better understand why they disappeared, but also to how they interacted with other populations who they coexisted with, like the Denisovans” says Bence Viola, assistant professor at the Department of Anthropology at the University of Toronto.

“To really understand the diets of our ancestors and cousins, we need more studies like this one that make use of multiple different methods on the same individuals. We can finally understand both the plant and animal foods that they ate”, offers Amanda G. Henry, assistant professor in the Faculty of Archaeology at Leiden University.

“The steppe lowlands of the Altai Mountains were suitable for the habitation of the Neanderthals 60,000 years ago. Despite the sparse vegetation and its seasonal character, the absence of tundra elements and relatively mild climate allowed eastern Neanderthals to keep the same food strategies as their western relatives”, says Natalia Rudaya, head of PaleoData Lab of the Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography Siberian Branch Russian Academy of Science.

Article:

Salazar-García D.C., Power R.C., Rudaya N., Kolobova K., Markin S., Krivoshapkin A., Henry A.G., Richards M.P., Viola B. (2021). «Dietary evidence from Central Asian Neanderthals: A combined isotope-plant microremain approach at Chagyrskaya Cave (Altai, Russia)». Journal of Human Evolution. Volume 156 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2021.102985

Link: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0047248421000373

Photo captions:

1. Neanderthal jaw studied in the work directed by Domingo Carlos Salazar García.

2 and 3. Chagyrskaya site.