|

||||

Textual Criticism – a Short Introduction

Contents:

§0. The problem with text. What is a text? What is textual criticism?

§1. The analysis of texts and their history.

§2. The editing of texts.

§3. Bibliography

§0. The problem with text. What is a text? What is textual criticism?

Four exercises 1 (pink) - 2 (Eliot) - 3 (Mona Lisa) - 4 (the readiness is all)Exercise no.1

Imagine a situation in which your best friend, John, sends you this message:

"Mary broke with me last might. I'm devastated. Please tell her I can't forget her, I can't forget when we first met at the Sex Pistols convert. I remember her spiky pink hairdo and the wasy she smiled at me while she sang 'God save the Queen'"

Complete the message that you send to Mary:

"He says he can't forget you, he can't forget .... "

Have you altered the text of John's message? What changes have you made? Why? What criteria have you followed to make alterations?

Option 1: "John says he can't forget you, he can't forget when you first met at the Sex Pistols concert. He remembers your spiky pink hairdo and the ways you smiled at him while you sang 'God Save the Queen'."

Option 2: "John says he can't forget you, he can't forget when you first met at the Sex Pistols concert. He remembers your spiky pink hairdo and the way you smiled at him while you sang 'God Save the Queen'."

Exercise 1-B

Imagine that John's message is as follows:

"Mary broke with me last night. I'm devastated. Please tell her that I can't forget when we first met at the Sex Pistols concert. I remember her jet black hair worn in a spiky pink hairdo."

Option 1: "John says he can't forget when you first met at the Sex Pistols concert. He remembers your jet black hair worin in spiky punk hairdo."

***

Exercise no. 2:

In his essay on the Jacobean playwright Thomas Middleton, the poet and critic T. S. Eliot refers to a passage in the tragedy The Changeling, in which the heroine Beatrice-Joanne confesses to her father:

"I that am of your blood was taken from you

For your better health; look no more upon’t,

But cast it to the ground regardlessly,

Let the common sewer take it from distinction."

Eliot used the text edited by Havelock Ellis for Mermaids series (vol. 1, London: Vizetelly, 1887, p. 164). However, the first line in the early substantive text and in most modern editions is

"I am that of your blood was taken from you"Any difference in meaning between "I that am of your blood" and "I am that of your blood"?

It should be remembered that bloodletting (the withdrawal of some of a patient's blood) was a usual medical procedure. Daalder glosses this line as "I am that part of your blood which, in purging, has been taken away from you to improve your health" (p.115).

Does it make any difference that Eliot misquotes from The Changeling?

As Kermode explains. Eliot "has made the speech over for his own purposes. [...] In preferring the incorrect version Eliot assumes accordingly that the lines are about family honour when the true reading makes it plain that Beatrice-Joanna has a different figure in mind: the shedding of her blood is compared to an act of bloodletting, phlebotomy, the medical opening of a vein, and not a blood sacrifice to satisfy family honour. The sewer carries away enough bad blood to assist in a cure. The mistake diminishes the passage and reduces the force of ‘distinction’ by associating it narrowly with ‘blood’ in the sense of honour; whereas, with the reading ‘I am that of your blood’, ‘distinction’ has a metaphysical force" (quoted from web version).

The misquoted line from The Changeling is reprinted elsewhere. For instance, as in David Daiches's A Critical History of English Literature, p. 334.

***

Exercise no. 3:

This exercise starts with F. W. Bateson’s famous question:

If Leonardo’s Mona Lisa is in the Louvre, where is Shakespeare’s Hamlet?

Is Hamlet in its earliest surviving text? This is the text printed in a quarto edition in 1603: it does not look like the standard version we know (See brief description).

Why cannot we state that Hamlet is in a specific place, just as we can with respect to a painting?

This is because “The medium of literature is language, which is abstract, not paper and ink, which merely serve as one vehicle for transmitting language. Therefore works of literature do not exist on paper, and the texts that appear there are only texts of physical documents” (Tanselle, “Textual criticism”, p. 1273)

We should therefore distinguish between Hamlet as a work, and the text of Hamlet.

Often critics use the term “text” to refer to a literary work, but from the perspective of textual scholarship we should make a distinction:

Text= “A text is a particular arrangement of words and marks of punctuation;

a literary work, a verbal construct, consists of a text (or succession of texts), but its text cannot be assumed to coincide with any written or printed text purporting to be the text of that work.” (Tanselle, “Textual criticism”, p. 1273)

A literary work is an intangible, abstract construct that needs a “text” (an arrangement of signs or instructions to reconstruct the work) to be transmitted, and this “text” needs a physical, tangible document (manuscript, printed, electronic) to contain or support it. Furthermore, the text in this document needs to be copied (transferred onto another document) in order to disseminate the work, and in that process of transmission alterations (accidental or deliberate) are likely to occur.

How successfully the texts contained in documents represent the literary work is a key question any reader and any critic should ask. As Tanselle explains, “the reason for questioning the texts of documents is that they are not the texts of works and that they may be faulty witnesses to those texts” (“Varieties” p. 12).

Exercise no. 4:

Take two or more editions of Hamlet, and compare Hamlet’s speech in Act 5, scene 2, replying to Horatio’s attempt to stop the duel because Hamlet seems not to be fit.

(Line numbers are 5.2.219-24 in the edition listed below as Evns1. The text reproduced here is the one edited by David Bevington for the Internet Shakespeare Editions <http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Annex/Texts/Ham/EM/scene/5.2#tln-3670>).

HAMLET . . . There is a special providence in the fall of a sparrow. If it be now, ’tis not to come; if it be not to come, it will be now; if it be not now, yet it will come. The readiness is all. Since no man of aught he leaves knows, what is’t to leave betimes? Let be.

[Commentary notes from Ard3Q2 :

If it be It is Hamlet’s moment of death, predetermined by God like ‘the fall of a sparrow’

since . . . betimes ‘Since no one has any knowledge of the life he leaves behind him, what does it matter if one dies early [betimes]?’ (Edwards)

Let be leave it alone; say no more. ]

It is possible to find more than ten different “texts” for this fragment! (see examples from different modern critical editions below)

Which is is the “correct” text, the most accurate text? Which one did Shakespeare write?

Textual criticism is the scholarly discipline that seeks to answer these questions.

Textual criticism “is the term traditionally used to refer to the scholarly activity of analyzing the relationships among the surviving texts of a work so as to assess their relative authority and accuracy. It is also often taken, more broadly, to encompass the activity of scholarly editing, in which the conclusions drawn from such examination are embodied in the text or annotation (or both) of a new edition.” (Tanselle, “Textual criticism”, p. 1273)

Why is it possible that we have texts of Hamlet with such a number and quality of differences?

As Tanselle points out, “Textual criticism is a historical undertaking” since its aim is “to elucidate the textual history of individual works and to attempt to reconstruct the precise forms taken by the texts of those works at particular moments in the past. Like all efforts to recover the past, it depends on judgment at every turn, and the word ‘criticism’ is therefore an appropriate element in the standard term” of textual criticism (“Textual criticism”, p. 1273).

As the text produced by a critic depends on her or his judgement, not two critics may coincide in their conclusions as to the history of the text, in their decisions to judge a segment of text as error, to emend an error by substituting the same emendation, or to modernize the words and punctuation according to the same criteria.

Let’s consider Hamlet’s speech in 5.2. 219-24 and trace the steps followed until the text is established in any of the editions sampled below.

The activity of textual criticism usually consists of two phases:

1) analysis of the texts and their history, investigating the documents textually related to the work in order to discern their nature, their genealogical relationship, and their degree of accuracy and reliability in transmitting the work’s text;

2) the establishment or editing of a new text (a critical text).

(This two phases are reflected in Housman's famous definition of textual criticism as "the science of discovering error in texts, and the art of removing it".)

§1. The analysis of texts and their history

In order to elucidate the textual history of the literary work (e.g. Hamlet) we first need to identify and examine the historical documents containing the texts (also called ‘witnesses’) of the work, with a view to dilucidate their relationships, relative authority and accuracy.

In the case of Hamlet, no manuscript, either by Shakespeare or a scribe, survives; only texts in printed editions in quarto and folio format published during the seventeenth century.

We compare these texts (word by word, punctuation mark by punctuation mark), keep record of their variants and examine how the documents were produced. In this examination, we are assisted by disciplines such as paleography, analytical and descriptive bibliography, historical linguistics and stylistics.

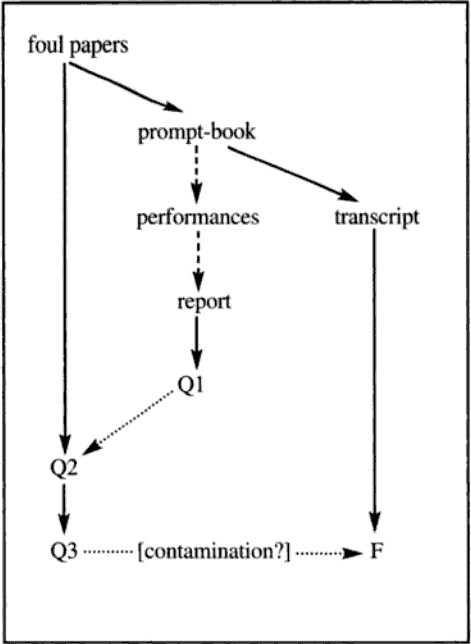

We analyze the variant readings in order to discern the relationships among the texts by identifying which derive from which (usually because they show common errors or unusual features that could not be made independently). We may then draw a kind of genealogical tree (stemma) showing which are the earliest texts that cannot descend from a previous one, how descendants can be arranged in “branches” or collateral lines of descent, and whether these lines converge because certain texts have combined readings from different branches of the tree.

In the case of Hamlet there are three ancestors or independents texts: chronologically,

- the earliest one, printed in quarto format in 1603 (Q1);

- the second one, also a quarto, with some copies dated 1604 and others 1605 (Q2);

- the third one, the text included in the collection, in folio format, of Shakespeare’s plays published in 1623 and usually referred to as the First Folio (F1).

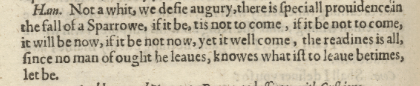

The 5.2.219-24 passage in the earliest edition (Q1) reads very differently from the one we are familiarized with. The following is a transcription from the photographic facsimile available at The Shakespeare Quartos Archive (for the facsimile, click on this link pages I2v and I3r , and look at the bottom of the left-hand page (verso page) and at the top of the right-hand page (recto)).

Ham. No Horatio, not I, if danger be now,

Why then it is not to come, theres a predestiuate prouidence

in the fall of a sparrow: heere comes the King.

This is the 5.2.219-24 passage as printed in Q2 (1604 and 1605) – page N3v at The Shakespeare Quartos Archive –:

and here as transcribed by Bernice Kliman in hamletworks.org :

Now the passage in F1 (1623) - page 280 from the Brandeis University copy -

|

|

|

and as transcribed by Bernice Kliman in hamletworks.org

What different meanings the Q2 and F1 versions provide?

The First Folio version focuses on the futility of earthly possessions.

The Second Quarto version ‘puts the emphasis on knowledge rather than ownership’ (ard3F p. 350); “ ... in Q2 is not a question of not having but of not knowing. This follows more naturally on the preceding acceptance of uncertainties; one cannot regret what one does not know. ... A more metaphysical meaning also may be in character for a hero whose frustrated inquiry into the nature of man gives way to an acceptance of man’s inability to know. What does it signify how soon we leave that which eludes our knowledge” (ard2, p. 565)

Comparing the three early texts

The First Quarto

The First Quarto version of Hamlet (Q1) has some 2,200 lines (about 40% shorter than the versions in the Second Quarto and the First Folio). Variation in the dialogue ranges from 32% of identical lines with F1, 28% of lines containing more than half the words in F1, 19% containing half or fewer of the words, 15% being a rough paraphrase, and 6% (around 130 lines) being unique to Q1 (Irace, p. 97), including a scene between Horatio and the Queen. Passages of identical lines noticeably appear in the roles of Marcellus, the ambassador Voltermar and the player Lucianus. There are notable transpositions of passages (e.g. the "To be, or not to be" soliloquy and its subsequent "nunnery" episode in the traditional Act 3 scene 1, is placed before the "fishmonger" episode in the equivalent to Act 2, scene 2). The name of Ophelia's father is Corambis (not Polonius), his servant is Montano (instead of Reynaldo in Q2 and Reynoldo in F1); and Ophelia's brother is Leartes (not Laertes).

The Second Quarto and the First Folio texts compared

The Second Quarto and the First Folio texts differ in over 1,000 verbal variants in the dialogue and stage directions, and a few variants in speech prefixes. Most verbal variants consist of substitutions or omissions/additions of one or two words, while very few variants involve rephrasing or transposition. Both texts contain coherent groups of lines that are only present in either (Q2 has around 230 lines in roughly 16 passages that do not appear in F1; and F1 has some 90 lines that are not found in Q2). Critics such as Edwards (cam4), Taylor and Wells, and Werstine ("Textual"), have observed a coherent pattern that relates some of F1's "omissions" to some of F1's "additions".

(Differences and similarities among the three early texts can be seen in Kliman and Bertram's transcriptions in parallel texts).

Discerning the relationships among these early texts is a complicated task, since not only Q2 and F1 agree in many variant readings against Q1, but also Q2 and Q1 have variants in common that differ from those in F1, and F1 and Q1 share a number of variants against Q2. Besides it is likely that the Q2 compositors consulted and were influenced by Q1, especially in the first act, and that the F1 compositors occasionally consulted a quarto reprint of Q2 (Taylor and Wells, p. 397).

Many textual critics agree that Q2 was printed from a manuscript in Shakespeare's hand (more likely a draft than a fair copy). The provenance of the F1 text has not garnered so much agreement, but most explanations indicate that it was printed from a scribal transcription, itself at one or two removes from Shakespeare's draft. Hibbard (oxf4) and Taylor and Wells argue that the F1 variants reflect a revision by Shakespeare himself, while Jenkins (ard2) discards any authorial revision. As for Q1, many critics support the hypothesis that it was reconstructed from a performance version, a reported text without a direct, visual connection to a written text; while some scholars argue that it corresponds to a version of the play earlier that that found in Q2 and F1.

For instance, Taylor and Wells represent the relationships among the early substantive texts in the following stemma (as reproduced in syn p. 49):

For detailed accounts of how three early texts of Hamlet came about, see introductions or the “textual analysis” sections in editions such as evns1, ard2, cam4, oxf4, Taylor and Wells and ard3Q2.

§2. The editing of texts.

Having analyzed the relevant early texts and concluded on an account of their transmission, the textual critic then needs to consider what kind of edition her or his readers will be best served with.

Types of scholarly editions

(See Tanselle, "Varieties of Scholarly Edition")

The editor may decide to reproduce one of the early texts without any alteration by means of a facsimile (now usually a photographic facsimile [example]) or of an accurate transcription (also called diplomatic transcription) that even records errors uncorrected [example of transcription]. Alternatively, she or he may decide that readers will be given better access to the literary work by means of a new text that alters one or various of the early texts with a view to reconstruct the text that existed or was intended at a given moment. In this case the new text is termed “critical” because the editor’s critical judgement is exercised in selecting among variants and/or in emending errors from a text chosen as the basis of the edition (called the base text, and in some practices "copy text" or "control text"). In contrast, facsimiles and diplomatic transcriptions are called “noncritical”. Here the role of judgement is restricted to choosing the early text to be reproduced and to discerning difficult readings (in an illegible handwriting or with typographical problems).

In all cases, noncritical and critical editors are expected to provide an account of their decisions, by means of an introduction and of annotations. In a critical edition, the editor is also expected to offer an account of how the new text has been established by means of a textual apparatus or collation (see later section on "The textual apparatus"). Usually, critical editions modernize the spelling and punctuation of the base text, a kind of "translation" process.

Finally, editors may annotate their new text (whatever the type) with glosses and commentaries (bibliographic, editorial, linguistic, literary, etc.) keyed to selected moments in the edited text.

Principles and procedures in a critical edition

In critical editing, a first decision is whether to reconstruct the text either as intended by its author(s) (in their original, intermediate or final intentions), or as made available to readers by publisher(s) and/or other agents at given times. The latter decision assumes that literary works are not only products of individuals but also collaborative and social products.

Moreover, two basic positions or attitudes can be adopted in relation to the base text(s): at one pole, a conservative stance; at a polar opposite, an interventionist or "conjecturalist" attitude ("eclectic", as termed by Greg 1942, p. xxvi-xxviii).

Conservative editing seeks to retain as much as possible the base text, emending only when there are manifest errors and keeping the reading in the base text when it makes sense). Interventionist ("conjecturalist" or "eclectic") editing corrects the base text not only when there are obvious errors but also when the editor finds probable errors, that is, when a given reading, compared to its variants or to editorial emendations, is judged less plausible to correspond to any intended reading than its alternatives.

In both positions, the editors' first duty is for the text they edit to make sense, and therefore they emend whenever the base text is certainly in error by restoring the presumed ‘original’ reading that was misread, misheard, faultily memorized or mistyped. Yet errors of transmission do not always and exclusively result in readings that make no sense; they also produce acceptable readings. Therefore, the logic of reconstructive editing favours an interventionist attitude in order to detect and emend where the base text is also probably in error, that is, where the editors suspect that something went astray during the text's transmission, even when the base text makes sense as is.

These two attitudes can be seen as constituting editorial 'principles' (the position that the editor assumes as a rule), and within each principle they can be seen as 'practices': a more or less conservative or interventionist application of the editorial principle assumed.

With a work that only has a single authoritative witness, the editor weighs the merits of every reading against those of later editorial (conjectural) emendations. With multiple authoritative witnesses, the editor weighs the merits of every reading against those of variants in collateral witnesses and of later conjectural emendations, in consonance with early history of the text's transmission inferred in the textual analysis.

Criteria in the editorial assessment of readings:

- coherence with the context

- rule of the "more difficult" reading, based on the assumption that copyists are less likely than authors to replace a reading for one more obscure and unusual.

- grammatical conformity with the state of the language

- compliance with metrical rules

- accordance with the author's linguistic habits and style (usus scribendi)

For a conjectural emendation to be acceptable, it also has to explain how the error in the base text was produced.

Let's get back to the 5.2.222-4 passage in Hamlet. Taking into account the history of the early texts of Hamlet as represented in the above stemma, an editor that purports to provide the version of Hamlet that Shakespeare revised will take F1 as his or her base text —e.g. Hibbard (oxf4 ) and Wells and Taylor (oxf2)—, while an editor that is not convinced that the differences in F1 are due to authorial revision may well be inclined to adopt Q2 as his or her base text —e.g. Evans (evns1) and Jenkins (ard2). Other editors are not persuaded by any specific narrative of the textual history and may opt for one of the early texts on other grounds — e.g. Thompson and Taylor (ard3Q2) choose Q2 because it is the longest text (p. 11), but they also provide critical editions of Q1 and F1 in a second volume of their edition.

The textual apparatus

The textual apparatus consists of a series of textual notes on segments of the text being edited that provide information on how the latter deviates from the base text as well as on variants from collateral, derivative and/or other critical texts. Textual collations may have different formats. The following one is common in Shakespeare editions:

166 There’s a] FQ1; there is Q2

First comes the number of the line in the new text containing the reading in question (“166”);

then the lemma or reading in question exactly as it appears in the new text (“There’s a”);

the lemma is followed by a closing square bracket; then the sigla indicating the text(s) that is/are the source of the lemma (“FQ1”, in this case both the First Folio and the First Quarto print “There’s a” –actually F prints “there’s a” but this difference is not substantial);

this is followed by a semi-colon;

then by information of alternatives in other texts using the same reading+siglum format (“there is” is the variant that appears in “Q2”, the Second Quarto).

Let’s look at the critical text and collation of Hibbard’s Oxford edition (oxf4) in the 5.2. 219-24 passage and compare it with the facsimiles of the First Folio and the Second Quarto shown above.

HAMLET . . . There's a special

providence in the fall of a sparrow. If it be now, ’tis not to

come. If it be not to come, it will be now. If it be not now,

yet it will come. The readiness is all. Since no man knows

aught of what he leaves, what is’t to leave betimes? Let be. 170

Hibbard’s is a critical, eclectic edition that takes the First Folio as basis. His textual notes are here transcribed (with an explanation on the right hand side):

|

166 There’s a] FQ1; there is Q2 |

(explained above) |

|

167 now] FQ1; not in Q2 |

Hibbard indicates that “now” in his text comes from the First Folio (coinciding again with the First Quarto) and that the Second Quarto omits this reading |

|

169-70 knows aught of what he leaves,] johnson; ha’s ought of what he leaues. F; of ought he leaues, knows^Q2; owes aught of what he leaves, hanmer; knows of aught he leaves, spencer; of aught he leaves knows aught, jenkins |

Here Hibbard indicates that he has emended his base text by replacing the First Folio reading “ ha’s ought of what he leaues.” with Johnson’s emendation “knows aught of what he leaves,”. Then he adds information about alternative readings from the Second Quarto and from other modern editions by Hanmer, Spencer and Jenkins. |

|

170 Let be] Q2; not in F |

|

Hibbard may have overlooked, or judged unnecessary to indicate, the fact that “all.” (with a full stop separating “The readiness is all” from the next phrase) deviates from F1’s “all,” (an alteration made by Rowe in 1709).

To conclude this introduction, you are recommended to read the MLA Guidelines for Editors of Scholarly Editions.

Examples of Hamlet’s speech 5.2.222-4 in different modern editions.

(editions are indicated by abbreviations listed below)

ard3Q2

If it be, ’tis not to come. If it be not to come, it will be now. If it be not now, yet it will come. The readiness is all, since no man of aught he leaves knows what is’t to leave betimes. Let be.

evns1

If it be [now], ’tis not to come; if it be not to come, it will be now; if it be not now, yet it [will] come – the readiness is all. Since no man, of aught he leaves, knows what is’t to leave betimes, let be.

ard2

If it be now, ’tis not to come; if it be not to come, it will be now; if it be not now, yet it will come. The readiness is all. Since no man, of aught he leaves, knows aught, what is’t to leave betimes? Let be.

cam4

If it be now, ’tis not to come; if it be not to come, it will be now; if it be not now, yet it will come – the readiness is all. Since no man of aught he leaves knows, what is’t to leave betimes? Let be.

pen2

If it be now, ’tis not to come. If it be not to come, it will be now. If it be not now, yet it will come. The readiness is all. Since no man knows of aught he leaves, what is’t to leave betimes? Let be.

alex

If it be now, ’tis not to come; if it be not to come, it will be now; if it be not now, yet it will come: the readiness is all. Since no man owes of aught he leaves, what is ’t to leave betimes? Let be.

oxf1

If it be now, ’tis not to come; if it be not to come, it will be now; if it be not now, yet it will come — the readiness is all. Since no man has aught of what he leaves, what is ’t to leave betimes? Let be.

oxf2

If it be now, 'tis not to come. If it be not to come, it will be now. If it be not now, yet it will come. The readiness is all. Since no man has aught of what he leaves, what is 't to leave betimes?

pen1

If it be now, ’tis not to come: if it be not to come, it will be now; if it be not now, yet it will come; the readiness is all, since no man has aught of what he leaves. What is't to leave betimes?

pen1 ] it will come; the readiness is all, since no man has aught of what he leaves. What is’t to leave betimes?

rowe1] it will come; the readiness is all; since no man has aught of what he leaves, what is’t to leave betimes?

pope] it will come: the readiness is all; since no man has aught of what he leaves, what is’t to leave betimes?

oxf2] it will come. The readiness is all. Since no man has aught of what he leaves, what is’t to leave betimes?

oxf1] it will come – the readiness is all. Since no man has aught of what he leaves, what is’t to leave betimes? Let be.

han1] it will come: the readiness is all. Since no man owes aught of what he leaves, what is’t to leave betimes? Let be.

alex] it will come: the readiness is all. Since no man owes of aught he leaves, what is’t to leave betimes? Let be.

cam4] it will come – the readiness is all. Since no man of aught he leaves knows, what is’t to leave betimes? Let be.

pen2] it will come. The readiness is all. Since no man knows of aught he leaves, what is’t to leave betimes? Let be.

oxf4] it will come. The readiness is all. Since no man knows aught of what he leaves, what is’t to leave betimes? Let be.

ard2] it will come. The readiness is all. Since no man, of aught he leaves, knows aught, what is’t to leave betimes? Let be.

ard3Q2] it will come. The readiness is all, since no man of aught he leaves knows what is’t to leave betimes. Let be.

syn] it will come; the readiness is all, since no man, of aught he leaves, knows what is’t to leave betimes. Let be

evns1] it [will] come – the readiness is all. Since no man, of aught he leaves, knows what is’t to leave betimes, let be.

List of works cited

Bateson, F. W., “Modern Bibliography and the Literary Artifact,” English Studies Today, 2nd series (1961): 66-77; reprinted in Essays in Critical Dissent (1972): 7-10.

Daalder, Joost, ed., The Changeling, by Thomas Middleton and William Rowley, New Mermaids (London: A & C Black, 1990)

Daiches, David, A Critical History of English Literature, 2nd ed (London: Secker & Warburg, 1969).

Greg, W. W., “Prolegomena. - On Editing Shakespeare,” in The Editorial Problem in Shakespeare (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1942), vii- lv, esp. xxvi-xxviii.

Housman, A. C., “The Application of Thought to Textual Criticism,” Proceedings of the Classical Association 18 (1921): 67-84.

Irace, Kathleen O., "Origins and Agents of Q1 Hamlet," in The Hamlet First Published (Q1, 1603): Origins, Form, Intertextualities, ed. Thomas Clayton (Newark, University of Delaware Press, 1992), 90-122.

Kermode, Frank. "Eliot and the Shudder", London Review of Books 32.9 (2010): 13-16. [ web version ]

Tanselle, George T. “Textual Criticism”, in The New Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics, ed. by A. Preminger and T. F. V. Brogan (Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP, 1993), 1273-276.

Tanselle, George T. “The Varieties of Scholarly Editing”, in Scholarly Editing: A Guide to Research, ed. By D. C. Greetham (New York: MLA, 1995), 1-32.

Taylor, Gary and Stanley Wells. “Hamlet”, in William Shakespeare: A Textual Companion, Stanley Wells, Gary Taylor with John Jowett and William Montgomery (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1987), 396-420.

Werstine, Paul, “The Textual Mystery of Hamlet,” Shakespeare Quarterly 39 (1988): 1-26.

Editions of Hamlet

(Abbreviations before a closing square bracket are from the “Hamlet bibliographies” section in Kliman et al., eds., hamletworks.org < http://triggs.djvu.org/global-language.com/ENFOLDED/edbib2.html>)

alex] Alexander, Peter, ed. William Shakespeare: The Complete Works. London and Glasgow: Collins, 1951. 1 vol.

ard2] Jenkins, Harold, ed. Hamlet. The New Arden Shakespeare. London: Methuen, 1982.

ard3Q2] Thompson, Ann, and Neil Taylor ed. Hamlet. The New Arden Shakespeare. London: Thomson Learning, 2006.

Bevington, David, ed. Hamlet. Internet Shakespeare Editions, University of Victoria, 2011. <http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Annex/Texts/Ham/EM/>

cam4] Edwards, Philip, ed. Hamlet, Prince of Denmark. The New Cambridge Shakespeare. New York: Cambridge UP, 1985.

evns1] The Riverside Shakespeare. Ed. G. Blakemore Evans et al. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1974. Illustrated. Hamlet, ed. Frank Kermode. Intro. pp. 1135-40. Text, pp. 1141-86. Note on the text and textual notes, pp. 1186-97.

F1] The Tragedie of Hamlet, Prince of Denmarke, in Mr. William Shakespeares Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies. Published according to the True Originall Copies. London. Printed by Isaac Iaggard, and Ed. Blount. 1623. pp. 152-280.

han1] Hanmer, Thomas, ed. The Works of Mr William Shakespear. Hamlet in vol. 6. Oxford: Printed at the Theatre. 1744.

Kliman, Bernice W., ed. The Enfolded Hamlet. In B. W. Kliman et al., eds., hamletworks.org <http://triggs.djvu.org/global-language.com/ENFOLDED/enhamp.php?type=EN >

Kliman, Bernice W., and Paul Bertram, eds. The Three Text Hamlet: Parallel Texts of the First and Second Quartos and First Folio. Ed. 2nd ed. New York: AMS Press, 2003.

oxf1] Craig, W. J., ed. The Complete Works of William Shakespeare. The Oxford Shakespeare. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1914. New York: Bartleby.com, 2000. <http://www.bartleby.com/70/4252.html>

oxf2] Wells, Stanley, and Gary Taylor, gen. eds. William Shakespeare: The Complete Works. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1986.

oxf4] Hibbard, G.R., ed. Hamlet: Prince of Denmark. Oxford Shakespeare Series. New York: Oxford UP, 1987.

pen1] Harrison, G.B., ed. The Tragedy of Hamlet Prince of Denmark. The Penguin Shakespeare. Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Penguin Books, 1937.

pen2] Spencer, T.J.B., ed. Hamlet. The Penguin Shakespeare. Introduction Anne Barton. Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Penguin, 1980.

pope1] Pope, Alexander, ed. The Works of Mr. William Shakespear. Hamlet in vol. 6. London: Jacob Tonson, 1723.

Q1] The tragicall historie of Hamlet, Prince of Denmarke by William Shake-speare. As it hath beene diuerse times acted by his Highnesse seruants in the Cittie of London: as also in the two Vniuersities of Cambridge and Oxford, and else-where. At London. printed [by Valentine Simmes] for N[icholas] L[ing] and Iohn Trundell, 1603.

Q2] The Tragicall Historie of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark. By William Shakespeare. Newly imprinted and enlarged to almost as much againe as it was, according to the true and percet Coppie. At London, Printed by I. R. for N. L. and are to be sold at his shoppe vnder Saint Dunstons Church in Fleetstreet. 1605 [some copies 1604].

rowe1] [Rowe, Nicholas], ed. The Works of Mr. William Shakespear. London: Jacob Tonson, 1709.

syn] Tronch- Pérez, Jesús, ed. A Synoptic Hamlet: A Critical Synoptic Edition of the Second Quarto/ and First Folio texts of Hamlet. València: Sederi/ Universitat de València, 2002.