|

Opening Hours:

|

|

In 2015, Juan Manuel Bonet and Salvador Albiñana presented at the Cervantes Institute of Paris and Juan Negrín Foundation, La biblioteca errante exhibition. Juan Negrín and the books. Now, with an identical title, Salvador Albiñana proposes a revised and expanded version of the exhibition in which the Republican printing has their best documentation during the war, the academic division of Negrín and the important catalogue of the España publisher (1929-1935), founded by Juan Negrín, Luis Araquistáin and Julio Álvarez del Vayo.

The scientific and politic importance of Juan Negrín López, creator of a prestigious Spanish school of physiologist and president of the Government of the Republic from May 1937, has left a dark zone for their interest to the books and reading. An initiated passion by his years as a Medicine student and teacher in Leipzig in which he become a bibliophile. It was very frequent to find him reading books and magazines in cafés when their leisure time and responsibilities allowed him - one of the closest friends, as the painter and illustrator Luis Quintanilla remembered.

Between Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, where he was born in 1892, and Paris, the city where he died in 1956, there were many geographies in Negrin’s life. Particular geographies by professional and familiar issues due to policy requirements from 1936, especially in 1939, when he left Spain and went into exile. Their books and documents travelled with him, although he hadn’t collect and access them until the end of the Second World War. What we call biblioteca errante (itinerant library) of Negrín is the effort to haul and gather fragments of libraries and documents that travelled from Madrid to Náquera and Barcelona in 1936. From their exile in France and England, there were distribute among Marsella, Andrésy, Paris, Bovingdon and Chiddingfold. Here are offered a small sample of one hundred-fifty titles, ordered by date of publication. A selection adhered to these books, magazines and leaflets, published in the years that he lived. Nowadays, these documents are conserved in their home, Paris.

Between Leipzig and Madrid, 1914-1936

In 1908, after two years of studies in Kiel, Negrín moved to Leipzig, where he completed their formation as a physician in the recognised Physiology Institute led by Theodor von Brücke. By mid 1914, the beginning of the Great War advised the return to Spain. It was when he started to acquire an ample medical library that was organized between his Madrid dwelling, the Faculty of Medicine - whose chair of physiology achieved in 1922 - and the Student’s Residence, in the newly created Laboratory of Physiology of the Junta para Ampliación de Estudios, whose management was offered by Santiago Ramón y Cajal in 1916. According to their disciple, Severo Ochoa, it was the most complete library in Spain focus on biology studies in this time.

Sciences, Humanities, Arts and Politics are confused in their library because they were confused in their live too. Karl Jaspers or Blas Cabrera, the outstanding divulgator of the Einsteinian relativity, lived with Valle Inclán, George Grosz or Pedro Salinas, whose first book, Presagios, was dedicated to the poet in 1924. In this year, his name appeared along with Azorín, Enrique Díez-Canedo, José Moreno Villa, Ramón Gómez de la Serna, Max Aub, José Bergamín or Luis Buñuel in the list of subscribers - a luckily compendium of Silver Age in Spanish culture - of the posthumous plaquette dedicated to the poet José de Ciria y Escalante. In 1927, he was appointed executive secretary of the Junta Constructora de la Ciudad Universitaria de Madrid, an institutional initiative that regained their breath with the Republic. In this task, according to their concern on scientific renovation of Spain, he entrusted himself with great intensity until their voluntary resignation in 1934, when the increased political activity led him to request leave of absence the Chair. Thanks to their inclination for new architecture, the modern movement or bibliophily, are captured in Internationale Architektur (1925), by Walter Gropius; Paris de nuit (1933), by Paul Morand y Brassaï, the first nightlife photobook; works of the singular urban planner Nicolau Maria Rubió; or the initial number of Papyrus (1936), magazine of the Barcelonan bookseller Josep Porter.

In the mid-20s, the time that his dedication to experimental research was decreasing - without neglecting the work of their disciples - their interest to politics was growing up. In 1926 he was one of the signatories of the founding manifesto of Acción Republicana, and in 1929 he joined the PSOE. He was the first prominent scientist to join the socialist movement. At that time, with his friends Luis Araquistáin and Julio Álvarez del Vayo, he founded the Spain label, an example of the modernising eagerness of the 1914 Generation - the first university and Europeanist generation.

The publishing house was inaugurated with the pacifist novel by Erich M. Remarque All Quiet on the Western Front (1929), whose translation was made by Eduardo Foertsch and Benjamín Jarnés. It was a great success that soon reached nine editions. Out of this varied catalogue –active until 1935– we can mention Mis peripecias en España (1929), by Leon Trotski, translated by Andreu Nin; Vieja y nueva moral sexual (1930), by Bertrand Russell, with Manuel Azaña as translator; El asalto (1930), by Julián Zugazagoitia, a social novel that mixes fiction and reality; El cáncer de útero (1931), a pioneer study by Sebastián Recasens; Elementos de bioquímica (1932, 3rd edition), the first university manual on discipline, written by his disciples José Hernández Guerra and Severo Ochoa; or ¡Écue-Yamba-Ó! (1933), Alejo Carpentier’s first work.

De Madrid a Náquera y Barcelona, 1936-1939

Until 1936, Negrín's library, although dispersed throughout different laboratories and homes in Madrid, was static. The situation changed at the end of the year, when the Government, in which Negrín carried out the Treasury portfolio, decided to settle in Valencia. Then was when his books began an uncertain exodus that the war and the vicissitudes of exile turned to labyrinthine. From Madrid they were transported to Náquera, to the urbanization La Carrasca, where some ministers had moved. At the end of 1937, along with a new transfer of the Government, they travelled to Barcelona and were installed in their residence of Pedralbes until January of 1939.

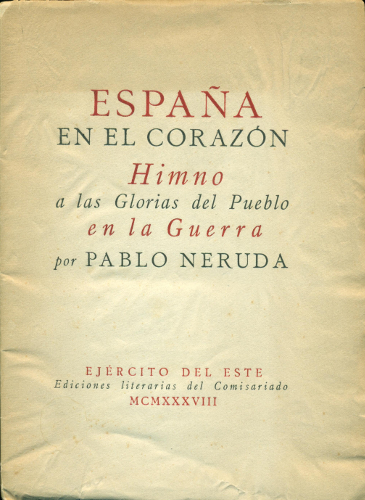

Ejército del Este, Ediciones literarias del Comisariado, MCMXXXVIII, 7 de noviembre de 1938

The Negrin library offers a wide record of Republican press. The works of the General War Committee for which Gabriel García Maroto prepared the well documented Propaganda y cultura en los frentes de guerra (1937) must be mentioned. Part of this edition was assigned to the participants of the Intellectual Congress for the Defence of Culture, gathered in Valencia in July that year. Other artists and designers were Arturo Souto, Josep Renau, Castelao, Ramón Gata, Mauricio Amster, Ramón Puyol or Manuel Ángeles Ortiz, who illustrated with color lithographs Guerra viva (1938), a poemary by José Herrera Petere, published by Ediciones Españolas.

We must also remember editions of the Public Instruction and Health Minister and the austere prints of the General Direction of Fine Arts, led by Josep Renau. Memoria de la Oficina de Adquisición de Libros (1937) belongs to that series. It is written by María Moliner, who worked as the director of the Library of the Universitat de València by then.

Signed by this publicist and addressed to the international public opinion, La lucha del pueblo español por su libertad (1937) stands out along with Work and war in Spain (1938), two photobooks that were edited by the Spanish Embassy in London with agency pictures, some of them by Robert Capa or David Seymour. Paris was a great editorial centre. Hommage à Federico García Lorca, poète fusillé à Grenade was published there, exposed in the International Exhibition of Paris of 1937; a French version of the speech pronounced by Manuel Azaña in the Universitat de València on 18 July 1937; Espionnage en Espagne (1938), Stalinist libel against the POUM, prolonged by José Bergamín and signed by an non-existent Marx Rieger that was actually probably Wenceslao Roces; and pamphlets like Les 13 points pour lesquels combat l’Espagne (1938), programme of the Negrín government, whose translator was André Malraux. The first edition of this political manifest specified conditions for a negotiated peace that did not indicated any artistic authorship and has a photomontage in the cover that is attributed to Antonio Ballester. Closing the Republican catalogue, España en el corazón by Pablo Neruda ended its printing in November 1938 in the old presses of the Montserrat monastery, watched by Manuel Altolaguirre. A very valued copy ─the 9th of an edition of 500─ of a book that is registered in a few libraries.

Bibliotecas en el exilio, 1939-1956

Near defeat, Negrín's books and archives travelled from Barcelona to Toulouse and Paris, although the documents most closely related to the war ended up in Marseilles guarded by the Mexican embassy. Negrín left Spain on 6 March 1939 and moved to Paris. He spent almost a year there. The German advance forced him to leave France and in June of 1940 embarked with destiny to England. Before doing that, he left his library in Andrésy, a city near Paris, guarded by a Republican public notary.

Negrín arrived in London without any book, but he soon began gathering a new library. Between 1940 and 1946 he frequented Oxford and London libraries and gathered an excellent collection. That library was located in Bovingdon, even though in 1946 it moved into another property ─Combe Court─ in Chiddingfold, South London. By then, some political and familiar circumstances advised him to stay in Paris. He stayed during 1947, even though the books he got in England remained there.

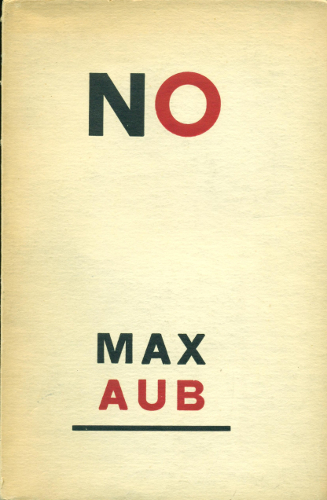

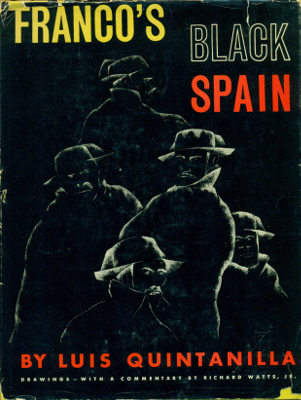

Once moved in again in Paris he got his books from Andrésy back and he had two libraries from 1947. That years’ books refer to the different reading entities of Negrín. From Franco’s black Spain (1946), dedicated to his author Luis Quintanilla; or Slightly out of focus (1947), the photographic story of Robert Capa, to the Cold War literature, and most of all about cybernetics, atomic physics or the beginnings of the European Economic Community. From the dealings with the cultural and academic circles they give account of dedications such as the very affectionate Albert Camus or the letter sent by the University of Paris in July 1956 with information about the International Congress of Physiology to be held in Brussels. Concerned with international politics, in April 1948 he wrote in the Paris Herald Tribune defending the inclusion of Spain in the Marshall Plan, an opinion that was strongly criticized in Republican exile. However, from Mexico he received friendly shipments: No (1952), by Max Aub - who, like Negrin, had been expelled from the Socialist Party in 1946; and Recordación de Cajal, a tribute celebrated in 1952, in which his disciples participated as Jose Puche, professor of physiology and rector of the Universidad de Valencia between 1936 and 1939.

Negrín died in Paris on 12 November 1956. At his will, he was buried, with discretion and sobriety, in the cemetery of the Père-Lachaise under a tombstone with his initials: J. N. L. After his death, the heirs were forced to liquidate the property of Combe Court which was very expensive to maintain. In 1958, Sotheby's announced the sale of about five hundred and fifty lots of books owned by a "Spanish Private Collector" that was Juan Negrín. Certainly, the repertoire was very valuable, with works like the Compendiosa Historia Hispanica by Rodericus Zamorensis (Rome, towards 1470); Novae veraque Medicinae (Medina del Campo, 1558), by Gómez Pereira, or the Prince edition of Traité élémentaire de chimie (Paris, 1789) by Antoine Lavoisier.

The books that were not sold at the London auction returned to Paris and remained in his home. It was Feliciana López de Dom Pablo’s task to guard that important heritage, the woman who shared her life with Negrín since 1925. When he died, in 1987, books and papers were taken care of by his granddaughter Carmen Negrín, who in 2001, with the help of Gabriel Jackson, began to order the valuable archive, currently guarded by the Juan Negrín Foundation in Las Palmas de Gran Canaria.

by Richard Watts, jr., New York, Reynal & Hitchcock, 1946.