What do we know currently about behavioural problems in children and adolescents? What are the causes and risk factors? What path usually follow these type of problems? How can we intervene? We will know the answer to all these questions and many more on November, during the conference “Effective treatments for negativist, violent and anti-social behaviours in children”, which will be taught by Alan E. Kazdin within the framework of the third edition of the International Congress of Clinical and Health Psychology on Children and Adolescents. The Congress will take place in Seville from 16 to 18 November.

12 june 2017

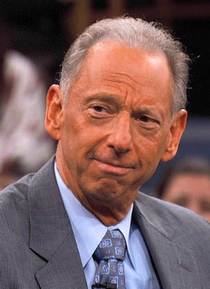

Dr. Alan E. Kazdin is Professor of Child Psychology and Psychiatry at Yale University (USA). There, he runs the Yale Parenting Center, a clinical service that offers psychological care to children and their families. During his whole career Professor Kazdin’s research has been focused on the treatment of violent and anti-social behaviours in children. He has authored more than 750 scientific publications and 49 books on psychological intervention with children and adolescents. Dr. Kazdin is an expert globally recognised by his contributions to the field of Child psychology. In 2008 he was president of APA, the American Psychological Association Recently, and he has been recognised for his work with the AITANA Award 2017, a distinction the Miguel Hernández University has given him due to the whole of his contributions to Clinical Child Psychology.

On the occasion of the awarding of the AITANA Award 2017 and his coming participation as a speaker at the 3rd International Congress of Clinical and Health Psychology on Children and Adolescents, José Pedro Espada, main researcher at AITANA Research, has been able to interview him:

-Professor Kazdin, first of all I wanted to say it is an honour to have you at this third international edition of the congress. Your career as a researcher and doctor is admirable. Could you tell us why did you decided to dedicate your work to the treatment of behavioural problems in children?

I started my career working in some places where it was necessary to change the behaviour of children and adolescents who were not functioning properly in their daily life. They were young people who had difficulties getting along with other people, following routines in home and school, and sometimes were a threat to their schoolmates and families. One of those occasions was when I was in charge for the Intensive Psychiatric Care Service for Children, an internment centre for children from 5 to 12. These children were interned for committing aggravated assaults and having anti-social behaviours, or for suffering depression and suicide risk. There we initiated specific research programmes, which we applied for various years.

Some of these children who presented aggressiveness and anti-social conducts had a parent or tutor with whom we could work along. Other children did not have parents, or their circumstances did not allow us working with them, due to drug addiction problems, because they were in prison or because they were prostitutes. Given these circumstances we designed two treatments, one in which parents were available, addressed to the training in parenting abilities, and other where parents could not be accessed and we only took care for the child, consisting in the cognitive training for problem resolution. We were lucky to have research helps for developing, perfect and study all these treatments for various years in the context of hospitalised patients and clinics.

- For many years you have managed the Yale Parenting Center, a service of Yale University that offers healthcare to children and families. What kind of problems usually have those parents that come to your centre and how is the help they receive?

The usually come due to problems related to their children. They present a great variety of symptoms related to behavioural disorders, among which there are fights, property destruction, thefts or home escaping. There are also other comorbid minor problems, such as oppositional behaviours and tantrums. Around a 70% of the children we help meet the criteria for two or more disorders. One issue that makes our work with them complicated is the severity and complexity of the situation of these children when they start the treatment. From parents’ perspective, their child seems to be completely out of control and they do not know how to manage the situation. Sometimes parents also present psychiatric disorders or drug-related problems. They currently have a lot of stress caused by their child’s problems, which join other daily circumstances such as difficult life conditions or economic problems.

In one of our clinical trials we have demonstrated that the child’s treatment has better results when we include a short module addressed to approach parents’ stress. We try to help families, and that means a lot more than just focus on the behavioural problems of the children. Our research programme has reached beyond the study of the results with the aim of understanding better the aspects that contribute to the problem, the profile of those who abandon treatment and why and who improve their condition, in addition to analysing the processes in the therapy that have an influence on its result. There are many aspects that cannot be put aside if we want the treatment to be effective; therefore we have established some related work areas. There are many challenges, more than we expected originally.

Our research programme has reached beyond the study of the results with the aim of understanding better the aspects that contribute to the problem, the profile of those who abandon treatment and why and who improve their condition, in addition to analysing the processes in the therapy that have an influence on its result.

- In your books addressed to new parents you approach the challenges educators find through the “Kazdin Method”. What are the key components of this programme?

Our programme includes three components to intervene in children’s education: Antecedents, Behaviours and Consequences (ABCs). For each one of them we offer several options of techniques that contribute to a behaviour change. For instance, when we speak about antecedents we refer to what happens before the behaviour and increases the possibility of development of the desired behaviour. Some examples of these antecedents are the way in which a petition is made, the parent’s tone of voice and facial expression, if there is some choice left after the petition, and if it is offered as a challenge that includes something ludic. Likely, in the Behaviour and Consequences components, there are many sides and specific techniques that can modify, develop and maintain behaviours. If we had to mention just one aspect on which this method is based it would be reinforced practice. We want to cause some behaviour and repeat it in order to develop a habit. We know that repeated practice can achieve this effect, and this practice produces changes in the brain.

Anyone who is reading this interview and plays and instrument will understand immediately what I am referring to. It takes practice to play an instrument properly. In our treatment programme the use of ABC is focused on encouraging the practice of the desired behaviour and making the child practice frequently and with motivation. The use of ABC and reinforced practice are fundamental in order to change the behaviour of both parents and children. Our programme is based on the applied behaviour analysis, the work area that has studied these techniques the most.

Our programme includes three components to intervene in children’s education: Antecedents, Behaviours and Consequences (ABCs). For each one of them we offer several options of techniques that contribute to a behaviour change.

- In your programmes for parents you approach the management of frequent situations in the education of children. What are the most important things for the parents to understand about how to change the behaviour of their children?

One of the main things may be that the techniques parents use naturally and think they work are usually inefficient to change behaviour.

I give two examples. In the first place, trying to reason with children to make them understand they must behave differently is not an efficient technique to achieve a behaviour change. Parents -in fact, most human beings- feel frustrated when someone close knows how to do something we would want them to change, but they keep doing it. Parents usually tell their children: “I have told you a thousand times not to do that, so stop it!” or “You know perfectly you should not do that and yet you are doing it”. This is a situation in which the child does not behave as the parent wants, and the parent does not understand it. Likely, we can tell our partner we do not like something he or she does. Our partner understands us, but keeps behaving the same way. We feel frustrated and surprised to see there has not been any change in this behaviour. Both in parents’ and partners’ cases we understand wrongly the failure to fulfil our efforts as something they do on purpose (for instance, my child is trying to manipulate me; my partner does not care...). Nevertheless, psychological research supports the assumption that these interventions are not an efficient way to change behaviour. When raising children, it is very important to explain and promote understanding, because this contributes to the development of problem solving, thinking and language strategies, and they can be used as a reasoning model for parents. Thus, understanding is necessary and important, but it is weak as a technique for change of behaviour and does not offer the effect many people expects it to offer. An important part of this training consists of developing more effective strategies for the behaviour change and giving them to parents. One of the aspects we try to transmit parents is that advocating, complaining and making the child understand probably are not the most effective ways for their child to develop a correct behaviour.

The techniques parents use naturally and think they work, such as trying to reason with children or punishing them, are usually inefficient to change behaviour.

In the second place, punishment is very usual and it is very present in the educational practices of parents. This is also understandable. For instance, a negativity bias seems to be connected by a cable in the brain and makes us identifying and paying special attention to the child’s negative behaviour. As a technique for behaviour change, punishment is quite inefficient except for stopping the behaviour in the same moment. Punishment does not develop the adaptive behaviours we desire and it is associated to many negative secondary effects. To delete the behaviour there are different efficient strategies that consist of training a positive behaviour or opposed to the one parents want to delete in the child. Therefore we cannot forbid two siblings to fight by containing or punishing them. It is better to reinforce systematically the situations in which the siblings are playing properly or cooperating. This would reduce considerably any fight and will be much more efficient short and long term. In some cases punishment can be necessary and a minor punishment can be useful as a complementary part of a programme to promote an adaptive behaviour. According to researches, parents are trained for using short and light punishments (for instance, being outside a reinforcement during five minutes or less, loss of a privilege during a night or a day, but no more).When parents use physical punishment we work very hard to delete it from their behavioural repertoire, considering the negative long-term consequences that physical punishment can have. Therefore, the second lesson we teach parents is not to rely in the utility of punishment and only use it in punctual cases such as the ones I have mentioned.

- Could you tell us some examples of parenting habits that should be improved to reduce or prevent behaviour problems?

I will give you three examples: in the first place, the use of punishment we spoke about previously. In most families we work with, it is fundamental to reduce the use of punishment. When children arrive to our centre, they usually have been previously in other treatments. Their behaviour in home and school is very annoying and generally much punished. Reducing parental trust in punishment requires providing alternative techniques to help them manage their children's behaviour.

The goal is not for the parents to know them, but to learn new tools with which they can get different results immediately. We begin by modifying a child's behaviour that is not very serious. The main objective is to change the parents’ behaviour. As parental skills develop, we address more serious behaviours. The key is to develop parents’ ability to focus on opposed positive behaviours, that is, prosocial or adaptive behaviours, rather than the behaviours they wish to eliminate in their child.

Three habits that parents should improve are the use of punishment, the focus on the gradual development of the desired behaviours and their repeated practice in calm and controlled situations.

Secondly, we emphasise, demonstrate and teach how to do it, gradually developing behaviours. Again an analogy with music training can help us to understand this idea. For a child who is beginning to learn to play a musical instrument, our goals are modest at first. Those initial goals might be to play loose musical notes first and then progress to play scales and arpeggios. Yes, we would like the child who just started playing the guitar to play the first day the Aranjuez Concert by Joaquin Rodrigo. Maybe child son is starting to play the piano and we would love her or him to come home after a class or two and play the Andalusian Serenade by Manuel de Falla. But that is not going to happen. However, through successive approximations we can achieve these objectives by modelling, encouraging repeated practice, using the reinforcement, in a successive way. Changes in the home can be appreciated faster than advances when learning to play a difficult musical instrument. However, parents do not model behaviour naturally, in part because they believe it is enough for children to understand how to do something, or that if they have done something one time, they must know how to do it every time. In this way it is not possible to establish behaviour change to develop stable habits and improve behaviour problems.

Third, often the behaviour the parents want their child to have does not occur or occurs with a low frequency. Repeated practice of the behaviour remains the primary goal, but how can we practice a behaviour that never happens? We use simulations in which the child practices the behaviour that the parent wishes to develop in very calm conditions. Our most common example is when a child has very explosive temper tantrums. These tantrums usually take place when someone tells them “no” to something. The child often screams and screams, beats the parents, breaks things at home and curses. We design the “tantrum game” in which the parent and the child act (role-playing). The tantrum is practiced under simulated conditions. The parent says "no" to some activity, but this is only simulated, and the child practices a "good" tantrum. In this game we use multiple antecedents, behaviour modelling and consequences (special reinforcements). Do not forget that the goal is to achieve a repeated practice. As practice continues, quieter and more "appropriate" tantrums may form within the simulated game. As a result, we begin to see that out-of-game tantrums (in everyday interactions) begin to change and parents can reinforce and model. In a short time (usually one to three weeks) the game can cease and the tantrums stop being so explosive. I must say that my description does not do justice to the range of behavioural change techniques that operate within the game I speak about.

The three examples reflect behaviours that we try to diminish or develop in parents. Interventions to change a child's behaviour are specific practices that parents carry out at home. Therefore, our treatment focuses on developing many specific skills in parents during treatment sessions.

- Based on your experience as a researcher and clinician, do you believe that child behaviour problems have changed over the years? What are the main challenges in this field?

One of the changes we have observed is that children who come to see a doctor due to behavioural problems are increasingly younger. Our clinical research began focusing on behavioural disorders in children aged 5 to 12 years. The usual profile was an 8-9 years old child. Over the years we get younger children, often for challenging and serious opposition behaviours. As expected, we have no cases of fights and destruction of property in 3-year-old children. However, we do not stop getting surprised. One of our 2-year-old cases had been expelled from three nursery schools because he punched other children. To adapt our work to a greater age range of children has been a challenge. Of course, it is much easier to work with children with oppositional and challenging behaviours than with adolescents and preadolescents with behavioural disorders.

One of the changes we have observed is that children who come to see a doctor due to behavioural problems are increasingly younger. Over the years we get younger children, often for challenging and serious opposition behaviours.

Perhaps the biggest change and challenge over the years is related to children's access to many sources of influence that promote aggressive and antisocial behaviour. Violent video games, violence on television and Internet access can foster those behaviours we are trying to change. Parents often have great difficulty controlling their children's exposure to content accessible through smartphones and tablets. Thus, exposure to violence has increased. In addition, drug use in the United States has increased and that has influenced both parents and young people, and has made treatment more difficult. There is another challenge that affects children's behavioural problems and that I can only slightly mention here: interpersonal violence (domestic violence) between parents in home, stress of parents and other family members (which has increased In the United States in recent years), and even climate change, to mention just three examples. They all influence aggressive and antisocial behaviour in childhood. All of this suggests that the development of treatments for behavioural disorder is not the most difficult challenge to achieve. Another way of saying it, evidence based treatments alone will not be enough to have an effect. Social and political changes that limit the influences that contribute to the problem are also needed. We are working on some of these other influences outside the treatment context.

- At your closing conference of the 3rd International Congress of Clinical and Health Psychology on Children and Adolescents you will address effective treatments for negativistic, aggressive and antisocial behaviours in children. What are attendants to your lecture going to learn?

In my lecture I will review the current situation of behaviour problems (oppositional, aggressive, violent and antisocial behaviours) in children and adolescents. Some of the issues I will address are: what do we know about the key characteristics of children and their families, the risk factors and causes, and course and long-term outcomes. A skill training process for parents with proven effectiveness will be presented. I will emphasise the range of techniques to intervene in the antecedents, the behaviours and the consequences to modify the behaviour. I will present the main results of our research programme. The results of our interventions indicate improvements in the child's behaviour, reduction of depression in parents, reduction of stress in the home and improvements in family relationships. I will also expose the contextual influences that contribute to aggressive and antisocial behaviour.

Let me conclude by mentioning that I am delighted with my next visit to Seville. I visit Spain whenever I can and immensely enjoy the people, their culture, and their customs. It is a privilege to be part of this international congress.

Thank you very much for your time and kindness, professor Kazdin. We look forward to seeing you in Seville.

Source: Infocop