In recent weeks there have been several news reports about a "meat-eating" bacterium that has caused the hospitalization of two young people for months. It is our bacterium under study: Vibrio vulnificus, which causes the disease called vibriosis.

In recent weeks there have been several reports of a "flesh-eating" bacterium that has kept two young women hospitalised for several months, even leading to the amputation of one or more limbs.

The first, a well-known actress and model named Jennifer Barlow, began to experience severe pain and swelling in her knee during her summer holiday in the Bahamas. On her return to the United States, she went into septic shock and was immediately admitted to hospital, where the pathogen was identified and treatment began. She spent five months in hospital, underwent multiple surgeries and finally had one of her legs amputated. She told the story herself on her social networks.

The second is a 40-year-old woman who was infected after eating infected fish. In this case the consequences were more fatal, as all four limbs had to be amputated in order to save her life.

You may be wondering who this pathogen is and how it produces these effects. It is Vibrio vulnificus, a bacterium very familiar to us as we work with it on a daily basis. And yes, as these cases show, it can cause amputations and even death in patients. But let's start at the beginning...

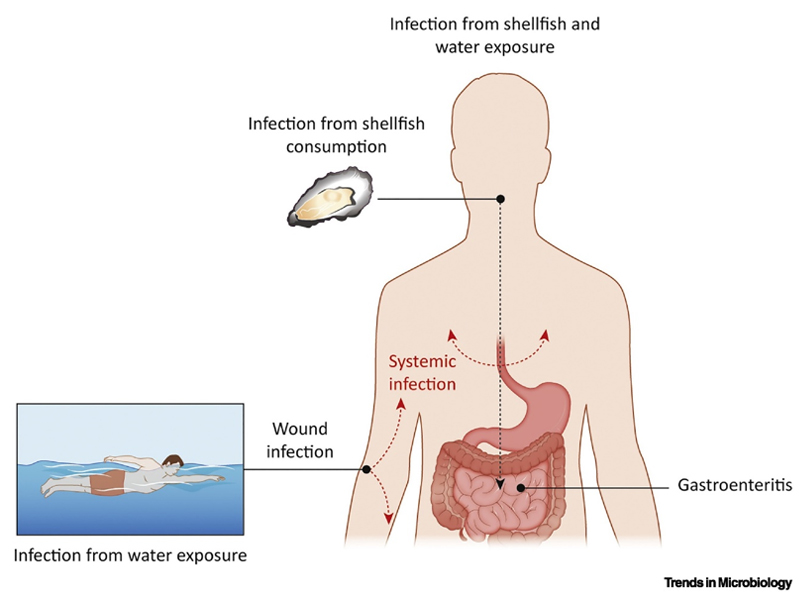

V. vulnificus is a zoonotic species of the genus Vibrio that inhabits brackish waters (those with more dissolved salts than freshwater, but less than seawater) in temperate and warm areas. It can live freely in the water column or settle on surfaces, both organic and inorganic. In particular, it often colonises the mucous membranes of fish or accumulates in filter-feeding animals such as bivalves or crustaceans. As a consequence of its way of life, there are two routes of infection in humans: by ingestion, which usually causes gastroenteritis and in more severe cases primary septicaemia; or by contact with seawater, through wounds, causing severe infections, amputations and secondary septicaemia (Figure 1). The two news items in question serve as examples for each of these routes. In the first, infection was caused by contact of an open wound with warm water in which the pathogen was present, while the second was due to ingestion of an infected fish, producing a life-threatening infection or vibriosis in both.

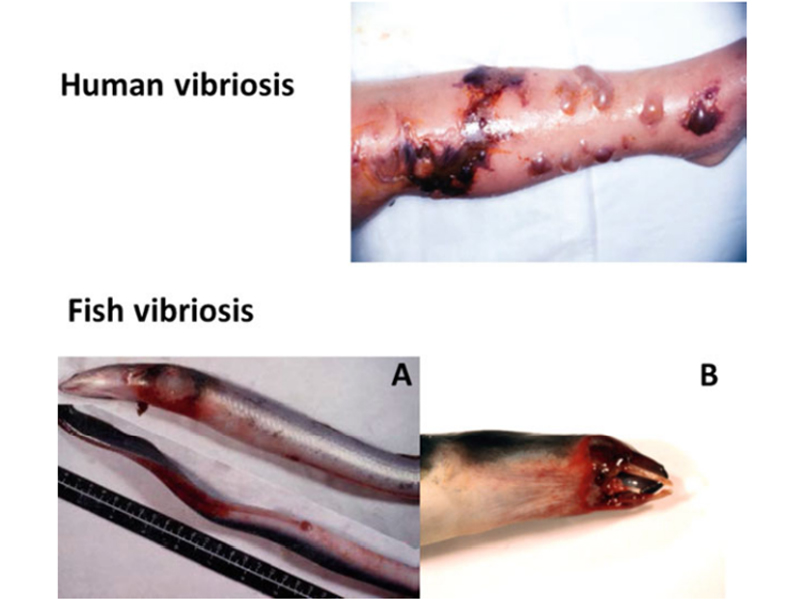

We know how it can enter, but which bacteria "eats flesh"? Symptoms of V. vulnificus infection include the appearance of blisters, bruising, erythema, inflammation... These initial skin manifestations can progress and lead to necrosis in both the skin and deeper layers, or in other words, the death of these tissues. Treatment is usually by debridement, which consists of removing the dead or infected tissue; and in more severe cases where the infection cannot be controlled, amputation of the limb is necessary (Figure 2).

In addition, V. vulnificus not only causes vibriosis in humans, but also in fish, mainly tilapia and different species of eel. As in humans, the disease is transmitted by contact or ingestion. When it occurs by contact, the pathogen is attracted to the mucus of the gills, colonises the mucosal surface and, depending on the condition of the animal, can produce superficial lesions or reach the bloodstream and cause death by haemorrhagic septicaemia. When ingested, it colonises the gut and can reach the bloodstream and also cause haemorrhagic septicaemia. Clinical signs in fish are very similar in both routes, with abdominal petechiae, haemorrhages at the base of the fins and reddening of the operculum region (Figure 2).

But don't panic, you don't have to stop eating fish or stay off the beach in summer. In fact, in most healthy patients, the symptoms remain a gastroenteritis or a localised infection. The problem arises in immunocompromised patients, patients with liver disease, elderly patients and people with haemochromatosis, where the likelihood of septicaemia can increase up to 80 times. However, even if the risk is low, prevention is always better than cure, especially now that this bacterium is spreading due to rising sea temperatures. For this reason, the CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) recommends avoiding the consumption of raw fish and shellfish and not swimming in the sea with open wounds.

References:

- Amaro, C., Carmona-Salido, H. (2023). Vibrio vulnificus, an Underestimated Zoonotic Pathogen. In: Almagro-Moreno, S., Pukatzki, S. (eds) Vibrio spp. Infections. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology, vol 1404. Springer, Cham. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-031-22997-8_9

- Baker-Austin, C., & Oliver, J. D. (2020). Vibrio vulnificus. Trends in Microbiology, 28(1), 81–82. DOI: 10.1016/j.tim.2019.08.006