In 1907, Antonio Lecha Marzo, a young medical student then, published a paper summarising the state of “knowledge about the scientific judicial police”; which had a prologue written by Salvatore Ottolenghi, the leading Italian figure in this field. Ottolenghi thought the scientific police had to be able to safeguard society “with human laws based on scientific progress” and to treat the criminal as a human being “and not as a beast”. In other words, the new scientific police had to bring together the knowledge of modern criminology (the study of criminal behaviour) and criminality (obtaining criminal evidence). The young Lecha Marzo was of the same opinion and considered “modern sciences” had transformed the concepts of criminality, punishment and criminal man. And he also replaced “the ancient and imperfect judicial investigation procedures” with “other more exact, essentially science-based ones”. This way, Lecha Marzo augured, “the characters created by the minds of Émile Gaboriau and Arthur Conan-Doyle will have real existence”. He mentioned the two most famous fictitious detectives of that time: inspectors Lecoq and Sherlock Holmes, respectively. These literary figures, along with lesser-known others, like Dr. Thorndyke of Austin Freeman, were a source of inspiration for the new scientific police.

According to Ian Burney, History professor at Manchester University, in the investigations of the imaginary detectives of crime novels many ingredients of the new scientific police can be observed: the protection of the crime scene to avoid contamination, the detailed collection of objects of that scene, including those more idle and trivial; and the detailed analysis, by means of techniques based on science, of all the available indications. This way of investigating, defended by authors such as Edmond Locard and Hans Gross, was based on teamwork and an indiciary system of evidence that was imposed in the 20th century and that has reached the modern scientific police.

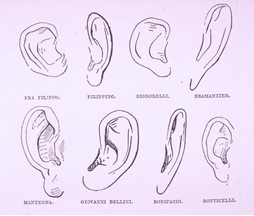

For decades now, the Italian historian Carlo Ginzburg defined this approach as the “indiciary paradigm”. In a bold article, he related this approach to the cognitive heritage of the first hunter-gatherers who had to pay attention to the tracks and traces left by animals. According to Ginzburg, the new way of knowing from tiny, apparently irrelevant details, arose not only in the new scientific police and in detective literature but can also be traced in the approach of art historians “like Giovanni Morelli who used small features (drawings of the lobe of the ear, the shape of the fingers) to distinguish between originals and fakes of paintings or to identify the true artist of a work. Like the dust spots or figures that fascinated the first scientific detectives, the features chosen by Morelli were apparently irrelevant. Ginzburg thought that these types of approach could have also influenced the work of young Freud, for example, in his interest for seemingly marginal aspects of behaviour, but very revealing from the point of view of psychoanalysis. And it was also behind the interest in fingerprints, the body features characteristic of criminology and investigations in the crime scene of the new scientific police. All of them wanted to know through “often infinitesimal indications a deeper reality that would be impossible to seize through other means”.

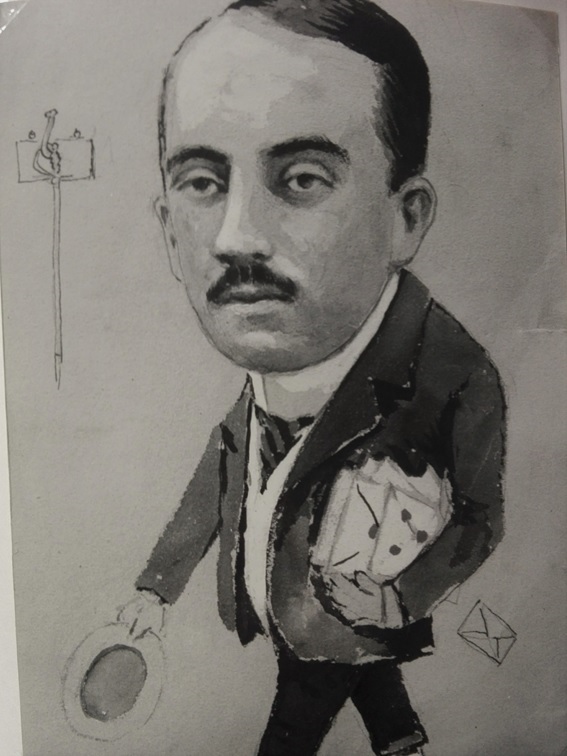

From his first collaborations in the legal medicine chair of his uncle at the University of Valladolid, Antonio Lecha Marzo was able to first-hand follow all these transformations. His research on some of the most characteristic forms of the new indiciary tests (fingerprints and blood and semen spots) also made him a major protagonist in the progress of scientific medicine in Spain. He was able to perform these works thanks to the new context for research that led to the creation of the Board for the Extension of Studies, of which he was one of the most outstanding scholarship holders abroad. His premature death in 1919 suddenly sharpened a brilliant career that was characterised by the wide interest in numerous lands related to criminal anthropology, the dactyloscopy, anthropometry and the detection of blood and semen spots. He also became interested in studies about the origin of the life of his time and maintained an interesting correspondence with the Mexican scientist Alfonso L. Herrera about plasmogenesis.

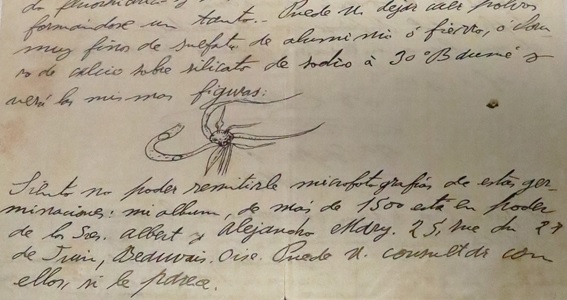

The personal archive of Lecha Marzo, which contains many other letters of great scientific value, has recently been donated by the family of the forensic doctor to the Vicent Peset Llorca library of the “López Piñero” Institute of History of Medicine and Science. Thanks to the work of the library team, under the direction of José Enrique Ucedo, this legacy is for the first time completely catalogued and available for future research. To celebrate this event, an exhibition, coordinated by Mabel Fuentes, has been organised, with a selection of the documentation, which opened on January 10, 2018 at 18:00 in the Palau de Cerveró of the University of Valencia. The inauguration will include the participation of the granddaughter of the forensic doctor, Carmen de Meer Lecha Marzo, who is also the author of one of the best bibliographical works on him. This way it is possible to know, with a great amount of bibliographic material, manuscripts and photographs of the time, the work of Lecha Marzo and the origins of the scientific police.

***

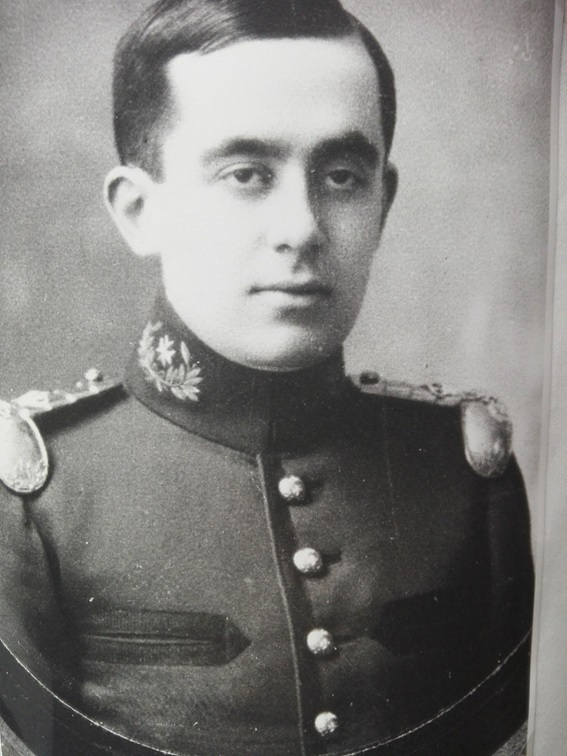

Antonio Lecha Marzo was born in Porac, a town on the island of Luzon, in the Philippines, on February 7, 1888. Son of a lieutenant of the Spanish army, he was orphaned and raised in the family of his uncle Lecha Martínez, professor of legal medicine at the Faculty of Medicine of Valladolid. Under the advice of his uncle, he began to study medicine and to collaborate in the work of the chair of legal medicine. It was during these years that he was interested in many topics he later developed: toxicological analysis, detection of blood and semen spots, thanatology and signs of death, and identification through fingerprints. Many of his most important works were published in these years, including the modification of the technique for the detection of blood through the use of iodine salts. As in other techniques of these years, it was based on the combined use of the microscope and reactions of the formation of chemical crystals. During these years he also worked on the improvement of the most famous method in this sense: the test introduced by Ludwig Teichmann in the mid-nineteenth century. During his years of student he also used microchemistry methods to solve other problems of the legal medicine: the identification of the sperm spots. He discussed the reliability of the methods based on the formation of Barbeiro crystals and, in subsequent publications, he studied the advantages of other reagents proposed at the time or the possibility of an individual identification, a recurring theme both in sperm and blood spots because of its importance as an indiciary evidence in various types of crimes.

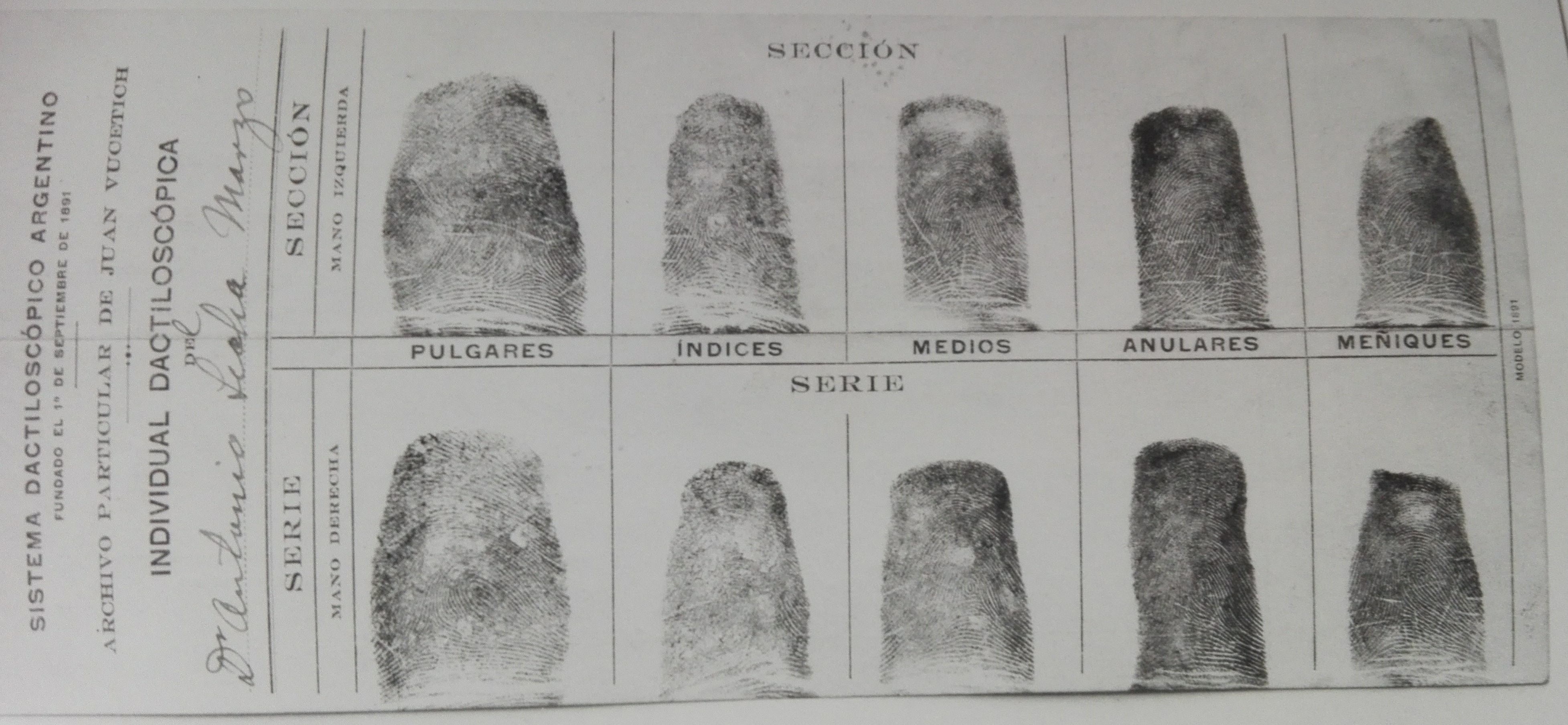

While progressing in his studies of microchemistry applied to legal medicine, Lecha Marzo also became interested in the new criminal anthropology and, in particular, in the work of Cesare Lombroso. In addition to the works published in 1906, Lecha Marzo performed a morphological study of the body of the anarchist Mateo Morral, author of the famous attack against Alfonso XIII, when he marched in his bridal carriage in Madrid. The new methods of identification that arose at the time were also of interest: the anthropometric review and the fingerprints. From 1907, he maintained a fluid correspondence with Juan Vucetich and Federico Olóriz, and carried out numerous publications to present his methods and defend the use of fingerprint in a wide variety of social life activities, from prisons to the scientific police, as well as for commercial or banking activities. Like Olóriz, he was a supporter of identifying the whole population through the universal use of fingerprints.

Lecha Marzo completed his studies in 1910 with an extraordinary degree prize and in 1911 he was appointed a doctor of military health. Thanks to a scholarship of the Board of Studies, Lecha Marzo was able to study at the Institute of Legal Medicine of Liege, where he prepared new publications on identification through fingerprints in collaboration with Henri Welsch (with whom he published a dactyloscopy manual) and through the palms of the hands, with Eugène Stockis. This was the central theme of his doctoral thesis he defended in October 1912.

After being appointed assistant professor of legal medicine at the Faculty of Medicine of Madrid, he began working with the chair of this subject, Tomás Maeste, with which he maintained an intense collaboration in his laboratory of legal medicine, and in the sessions of the Spanish Society of Biology, in which he presented several works, and, from 1914, in the new Institute of Legal Medicine and Toxicology. He also collaborated with the Criminological Institute and taught dactyloscopy courses at the Police School of Madrid, under the direction of the famous inspector Ramón Méndez Alanis. He was the host of Juan Vucetich, creator of the fingerprint system in Argentina, when he visited Madrid at the end of 1913.

In May 1914, his academic career culminated with his appointment as professor of legal medicine in Granada, which he combined with his collaborations with Maestre in Madrid. Subsequently, during the 1917-1918 academic year, he moved to the Faculty of Medicine of Seville.

In the last years of his life, Lecha Marzo continued to publish on his youth issues and was required by the law to prepare expert reports on forensic psychiatry and identification of corpses. His most famous case was the identification of the remains of a skeleton found in a house on the Cuesta del Rosario street in Seville. The judge suspected that he could belong to a collector of a mysteriously disappeared trading house in September 1877. Lecha Marzo took advantage of this case to show the possibilities offered by legal medicine to submit evidence to the courts “even after forty years after the crime was committed”. He also made contributions to forensic thanatology, in particular to the methods to diagnose death in a safe manner. As described in its Autopsy Treatise, one of the works that can be seen in the exhibition, Lecha Marzo proposed using “a sheet of tornacol paper applied to the eyeball, below the eyelids”. The sheet presented “blue coloration in the living subject” (since it is a basic medium), while “in the corpse, no change in coloration or red coloration is observed”, due to acidity. The trial was soon adopted by many forensic doctors who checked their efficacy and reliability.

As of 1910, after finishing medical studies, Lecha Marzo conducted work on the studies of the origin of life and colloidal chemistry. These works involved the use of chemical reagents and microscopic observations, connected, at least from the methodology point of view, with their investigations of toxicological microchemistry and the detection of blood and semen spots. He exchanged letters with several authors on this issue, in particular with Alfonso L. Herrera, who used the expression “plasmogenesis” to refer to these investigations, and Israel Castellanos, editor of the Boletín del laboratorio de plasmogenia de la Habana (‘Bulletin of the Havana Plasmonics Laboratory’). In one of the letters, which is now conserved in the Peset Lorca library, Herrera congratulated Lecha Marzo on the “merit and opportunity” of his work and invited him to continue “with all his delight”, despite criticism and difficulties.

His investigations in this and other areas were soon interrupted by the disease. After a trip to Barcelona in the summer of 1918, where he thought he could access the chair of legal medicine, he fell ill for a few months. Once recovered, he resumed his work as a teacher, asked for a new scholarship to the Board for the Extension of Studies, gave conferences and began the publication of the first fascicle of his Tratado de Medicina Legal y Toxicología (‘Treaty of Legal Medicine and Toxicology’) at the beginning of 1919. All These projects were frustrated by his death on May 19, 1919.

The exhibition organised by Mabel Fuentes, a student of the Master’s Degree in History of Science and Scientific Communication, is organised in sections that present four aspects of the activity of Lecha Marzo: the performance of autopsies for legal medical purposes; the correspondence with a large number of relevant characters from his time, including several postcards with his microchemical preparations; his relationship with the criminology studies of the time, with works by Cesare Lombros and Adolphe Bertillon; and his participation as an expert in the resolution of the crime of Cuesta del Rosario street in Seville, the most famous case in which he participated. TAll books, manuscripts and objects come from the Vicent Peset Llorca library and from the scientific and medical collection of the University of Valencia, from the “López Piñero” Museum of the Institute of History of Medicine and Science.

José Ramón Bertomeu Sánchez

“López Piñero” Institute of History of Medicine and Science

To know more:

Burney, I. and Pemberton, N. (2016): Murder and the Making of English CSI. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

De Meer Lecha Marzo, C. (1985): Antonio Lecha Marzo (1888-1919): contribución al estudio de la Historia de la Medicina Legal contemporánea. Valladolid: Doctoral thesis.

De Meer Lecha Marzo, C. (1988): Antonio Lecha Marzo y la Junta para Amplicación de Estudios. In José Manuel Sánchez Ron (ed.) (ed) La Junta para Amplicación de Estudios e Investigaciones Científicas, Madrid: CSIC.

Ginzburg, C. (1994): Mitos, emblemas e indicios: morfología e historia. Barcelona: Gedisa.

Martínez Pérez, J. (1991a): "El estudio médico-legal de las manchas de esperma en la obra de Antonio Lecha Marzo (1888-1919): un reflejo de la medicina legal española de su época", in Actas del V Congreso de la Sociedad Española de Historia de las Ciencias y de las Técnicas. Murcia 1, 1183-1198. Murcia: D.M.-P.P.U.

Martínez Pérez, J. (1991b): "La contribución de Lecha Marzo a la tanatología médico-forense", en Actas del IX Congreso Nacional de Historia de la Medicina, 1429-1442. Zaragoza: Prensas Universitarias de Zaragoza.

Personatges i espais de ciència (‘Science characters and spaces’) is a project of the Unit of Scientific Culture and Innovation of the University of Valencia, with the collaboration of the “López Piñero” Institute of History of Medicine and Science and with the support of the Spanish Foundation for Science and Technology and the Ministry of Economy, Industry and Competitiveness.

.jpg)