The flâneur that walks along the sidewalk of Quart Street, along the Botanic Gardens research building, may be surprised to know that place already has two centuries of history behind it. And that if we counted its age from its current location, dating from 1802; because, in fact, the establishment of the first Valencian university space dedicated to the study of plants is much more distant in time: it dates back to 1567. A few months ago, it was four centuries and a half old.

Indeed, on May 16, 1567, the city’s juries, meeting with the royal treasurer and other municipal officials in the Private Council chamber, agreed “that the chair of simples is awarded to the magnificent Joan Plaça, doctor in medicine, with fifty pounds royal coin of Valencia as ordinary salary and fifty more pounds of such coin as cost help each year, with which he may follow the reading order the magnificent board members assign to him”.

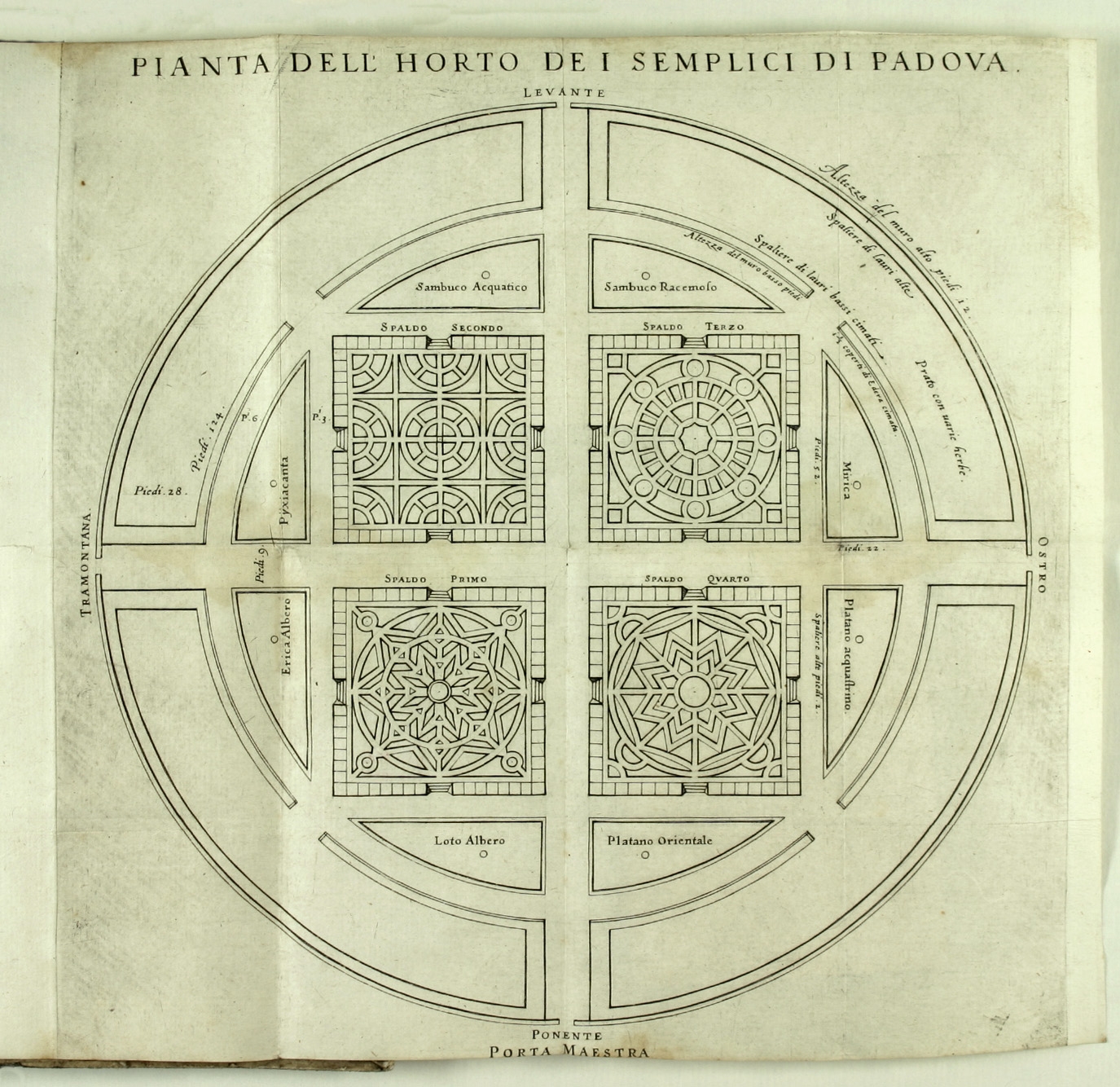

In the chair of simples, also called “chair of herbs” in other documents of that time, Valencian medical practitioners were taught everything that referred to the medicinal simples, that is, the elements of the three kingdoms of nature (animal, mineral, but mainly vegetable) that had medicinal properties, according to the medical theories of the time, based on the Hippocratic and Galenic doctrines. The teaching of this subject from a chair specifically dedicated to it was relatively recent; in fact, the first chairs of herbs and the first orchards of medicinal simples had been created twenty years before in some Italian universities (Pisa, Padua, Bologna), as shortly after was done in Montpellier (although its garden was created much later) and, finally, also in Paris and Valencia.

[Image 1: Orto botanico (‘botanical orchard’) of Padua founded in 1545. Floorplan by Girolamo Porro, 1591]

The agreements of the Valencian municipal government regarding the teaching of medicinal plants went beyond the appointment of a teacher and the setting of a wage, generous enough, by the way. Thus, the aforementioned document continued to establish that among the obligations of Plaça there was one regarding going “outside the present city for 30 days through the mountains and other places when and as many times as he considered in order to show students how to get to know herbs”.

This command meant providing Valencian medical education with a very interesting and innovative practical aspect, since up until that time the didactic methods of the university had almost exclusively been theoretical, based a lot on reading, commenting and glossing classical texts and poorly oriented –with the exception of the anatomic dissection territory– to value practical experience as knowledge generator. On the other hand, it is quite interesting to see how the city opened up the possibility of acquiring this knowledge for other people, beyond the strictly university public; which was also done in relation to anatomic dissection. Certainly, surgery and apothecary apprentices, both in the case of the dissections and the herbs harvesting outings in the surroundings of the city, up to the mountains, were the first collectives to benefit from this opening to new audiences of these university activities.

We thus arrive to the third agreement adopted by Valencian jurors that spring morning of 1567; always referring to the obligations of the new simples professor, it commanded that “you take care of an orchard in which the herbs you deem necessary are planted, giving you an appropriate place where there is said orchard and gardener in charge of cultivating it and keeping track of the apothecary shops”.

Everything suggests, then, that this is the first provision for the creation of a university botanic garden in the city of Valencia. Unless some unknown document appears, it is also the earliest documentary experience referring to a city in the Iberian Peninsula. This Valencian pre-eminence is not surprising if we consider the long tradition of the city –and of its university studies– regarding the cultivation and study of medicinal plants. Suffice it here to remember the herbs harvesting of Pere Jaume Esteve (1500-1556) in the Penyagolosa, or the presence of Valencian gardeners and herbalists at the courts of Charles V and of other members of the Habsburg dynasty.

However, we need to somewhat stop to consider the terms and the uniqueness of this new space of science.

First of all, its close relation with the teaching of the medical matter, that is to say, of the simple medicinal ones is clear. In fact, the name “garden” and the adjective “botanical” do not appear, or will appear, in documents until much later. What interested in the university education of those times was a knowledge of the plants oriented towards medicinal therapy; neither Botany (like that, with capital letters, as a scientific discipline), nor the botanists (as a scientific profession) existed in the sixteenth century, although many times –with an anachronism that should be avoided whenever possible– we use these terms to define know-how, practices or people dedicated to the study of the natural world in times of the past when they really did not exist as such.

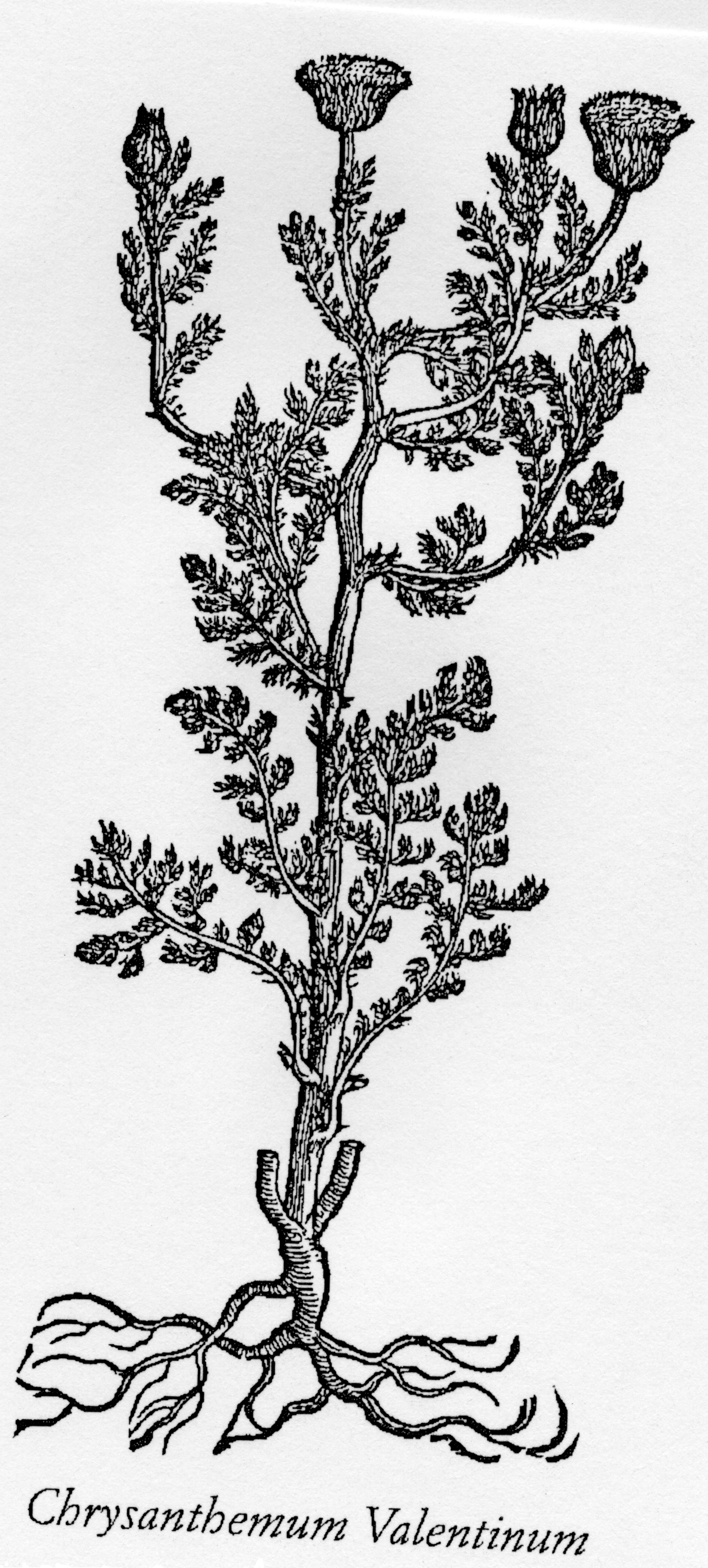

Secondly, it is very interesting to see how the municipal government gives the university professor a wide margin of choice about what to do and how to do this “orchard”, what should be planted in it, what that gardener who is supposed to be contracted must do and how to control the money used when purchasing seeds or samples from apothecaries stores. And the skill and knowledge of Joan Plaça (ca. 1520-1603) in 1567 were well known by the city’s governors. And not only by them. Three years before his appointment, the flamenco botanist Charles de l’Écluse (better known by his Latinized name Clusius, 1525-1609) was in Valencia, and he made Plaça his correspondent and a fundamental collaborator for the Iberian flora that he prepared during his tour around the peninsula in 1564 and 1565, work that finally Clusius would get published in 1576. In that book, titled Història de diverses plantes rares observades a les Espanyes [Rariorum aliquot stirpium per Hispanias observatarum historia] (‘History of several rare plants observed in the Spanish territories’), there are up to seven species that bear the “surname” Valentinum or Valentina in its scientific name granted by Clusius, as a result of its recognition of the Valencian origin of the specimens, most of which are provided by Plaça, along with other species that were sent to him thanks to the shipments of Joan Plaça, as Clusius himself admits in his book.

[Image 2: Engravings of the Chrysanthemum Valentinum ad of the Hemerocallis Valentina, published in Per Hispanias, by Carolus Clusius in 1576]

Plaça remained the head of the chair and of the medicinal herbs orchard until 1583, when he went on to occupy the chair of medical practice. But he continued as an indisputable authority in the matter, until he died in 1603, as evidenced by the official approval he made at the Officina medicamentorum, the first Valencian pharmacopoeia, published in 1601 by the School of Apothecaries of the City, as a result of the knowledge and practice accumulated for decades in the area of Valencian apothecaries and the teaching of medical botany in the General Study and in his “orchard”.

However, we do not know much about the specific development of this space during its first decades of life. It may even be that the first orchard, the one in times of Joan Plaça, would be out of service at some point, because in the Constitucions del Estudi General (‘General Study Regulations’), published in 1611, despite the fact that the distinctive features of the teaching of herbs are clearly specified and that “orchards” is mentioned, they do not make a clear specific reference to a university orchard. After establishing the theoretical content of the classes in the classroom (“The professor of simples or herbs will read as usual from two to three, and will read the Universal Method and the fourth and fifth book of simplicium medicamentorum facultatibus”, referring to the two therapeutic treatments of Galen), mapping the natural environment of the city, pointing to natural spaces closely linked to the “artificial” space of the orchard and shows the close connection of the Valencian orchard in the city and to the knowledge that was circulating there, when he indicated that he was still obliged to leave with students to harvest herbs “in the usual places” and lists the order of these scientific trips: “that the first one takes place in the orchard, the second one around several parts of the garden, the third in the cliff of Carraixet, the fourth in the cliff of Torrent, the fifth in the Murta”.

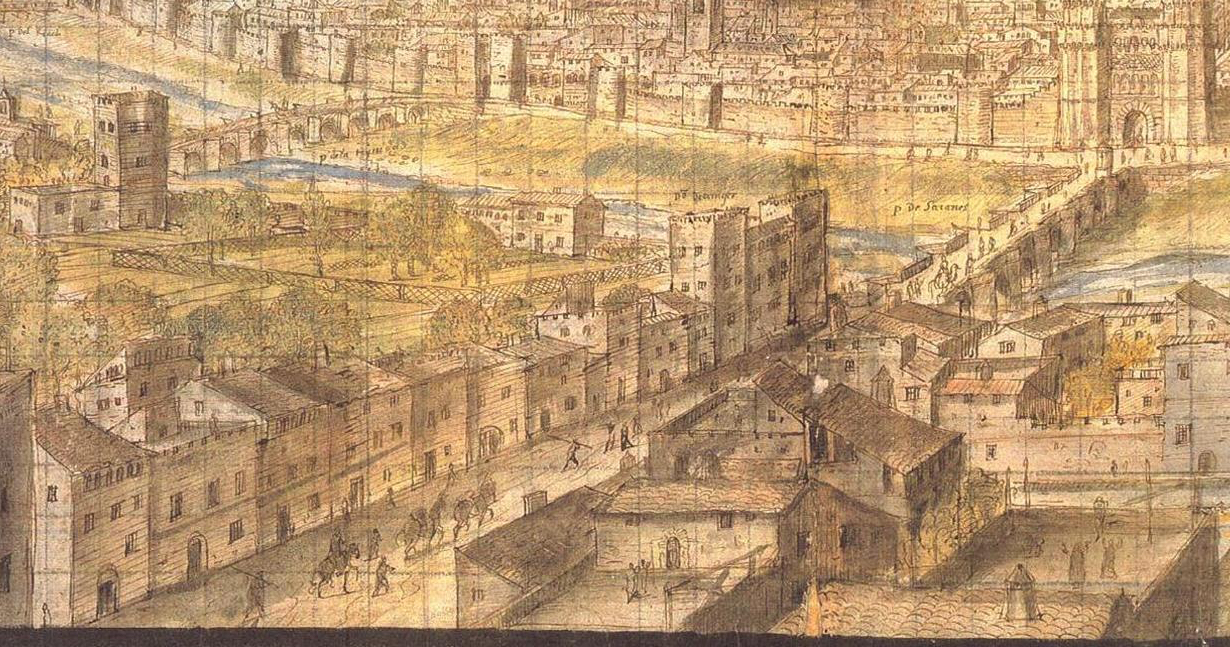

The documentation so far exhumed by scholars allows us to know another chapter of the history of the city’s spaces dedicated to teaching and looking for plants, about twenty years later, in 1631. In this new episode, the professor of herbs was Gaspar Pons, who, along with other medical professors, but also (and this aspect should be especially emphasised, because it means the joint action of the citizens groups interested in this type of knowledge) surgeons and apothecaries of the city, demanded the lease of orchards to be able to cultivate and teach medicinal plants in them. This was done, and in 1633 the city rented two orchards located on the banks of the other side of the river, past the Serrans bridge. Located next to the convent of the Augustinian nuns of Sant Julià, on the Camí de Morvedre (now Sagunt street), the documentation presented by Amparo Felipo relates the property of these gardens with the Sant Llàtzer Hospital, located at the same street.

[Image 3: The road of Morvedre, according to the drawing Anton van den Wijngarde did of the city during his trip in 1563]

We know that the orchards were now, in fact, two; that the activities there were performed under the responsibility of a board chaired by the city’s ombudsman and formed by the herbs professor of the general Study, the treasurer of the College of Surgeons and the trustee of the College of Apothecaries; and that a gardener was hired and was given a home built next to the women’s hall of the Sant Llàtzer Hospital, that depended on the general Hospital of the city. That is why the Hospital administrators were the ones who, on March 17, 1633, provided the installation of “the bedroom for the gardener in a room of the said Sant Llàtzer General Hospital, named the women’s hall, where there are two bedrooms and one kitchen, in the wall of which, leading to the second orchard that faces the door of the Morvedre road, a small door needs to be done and is done, so there is access to and from the other orchard, which is above the aforementioned Morvedre Street”.

Half a century later it seems that those orchards on the grounds of Sant Llàtzer were no longer useful or viable. However, the ideal place to continue the cultivation of simples and their teaching to university students of medicine, apothecaries and surgeons, remained the suburbs around the Morvedre road, because a new orchard and a new house for the gardener were bought there, this time around the Col·legi de Sant Pere Nolasc, adjacent to the orchard Dr. Lluís Agramunt already had there. Indeed, in 1684, in spring again, the authorities of the Municipal Council, together with those of the colleges of surgeons and apothecaries, had decided to give “powers of sole administrator” to Gaudenci Senach, herbs professor of General Study to purchase or rent “a house and orchard or gardens, where you would deem more appropriate”, “to renew said orchard of medicinal herbs”.

For now we do not know much more about the evolution of the university simples orchards of the Morvedre road. The Regulations of the University, published in 1733, insisted on the necessity of having an orchard for the teaching of medicinal simples, which has led historians to think some event interrupted it. Perhaps the events subsequent to 1707, although it seems that during the teaching of Antoni Garcia Cervera, from 1721 to 1732, that the “herbs orchard” remained under his responsibility. By now, regarding documents, we should wait until the university reform of dean Vicent Blasco to know a new episode around this kind of university facility. However, around 1787 –year of publication of the curriculum of the reform by Blasco– its characteristics had significantly changed.

As the enlightened movement acquired power to promote and launch scientific and cultural companies inspired by the new philosophical, economic and political trends, the teaching of sciences considerably changed. As for the old orchards of medicinal herbs aimed at the training of doctors, surgeons and apothecaries, they were transforming in a very remarkable way. It was then, at the end of the eighteenth century, when botanical gardens were referred to as such.

Thus, new spaces were more oriented to the cultivation and the study of all the vegetal species, both of the native flora and of that exotic and distant one, which was a fundamental piece for the maintenance and exploitation of the European colonial empires, among which the Spanish one, which was still the largest of all. The dedication of part of these new botanical gardens to medicinal herbs never completely disappeared, but the fundamental objective became the one to own and exhibit the greatest possible number of families, genera and species of plants; in addition to controlling and widening the knowledge of species with great economic potential from the colonies.

The great taxonomic revolution that meant the acceptance –not without a good handful of years of controversy– of the classification proposal of Carl von Linné (1707-1778) helped to remodel most of the pre-existing university gardens and to design new ones, inside and outside the strict framework of the university institution.

In Valencia, the curriculum of Blasco already spoke of having a garden for the global study of botany. The clearest attempt in this regard was that of the collaboration project between the University and the Royal Economic Society of Friends of the Valentian Country, created some years before, in 1776. The city transferred land near the Albereda (‘poplar avenue’), to the side of the so-called Pla del Real, although everything suggests that the garden has not finished developing all its functions, due to problems and tensions between the institutions involved in the project.

[Image 4: Print representing –with a bit of imagination– the botanical garden near the Albereda (‘poplar avenue’)]

We thus arrive to 1802, when the still dean Blasco, who was definitely convinced of the impracticality of the garden next to the Albereda, commissioned Francesc Gil, who later became “botany senior lecturer” of the Valencian University (see the symptomatic change experienced by the name of the chair), the design of a new botanical garden on the grounds of the so-called Tramoieres orchard, located in the north-western part of the Quart road.

[Image 5: Fragment of the Valencia map by pare Tosca, where the Tramoieres orchard is clearly visible, at the beginning of the Quart road]

Just one year earlier Antoni Josep Cavanilles (1745-1804) was in charge of the Royal Botanic Gardens of Madrid, which is why it is not surprising to find that he advised Blasco and wanted to actively participate in the project. Plants from the Albereda garden were transferred to the Tramoieres orchard and also plants from the garden that the archbishop of Valencia Fabián y Fuero (1719-1801) had created in Puçol in 1777, which since then was an important space for the acclimatisation of exotic plants in the Valencian lands (Fabian had been bishop of Puebla, in Mexico, before being appointed Archbishop of Valencia in 1773).

The characteristics of the new Valencian botanic garden fully represented, thanks to the design of Gil, the influx of Cavanilles and the direction from 1805 of Vicente Alfonso Lorente (1758-1813), the new vision of this classical space of teaching and creation of scientific knowledge about the plant world. From a strongly taxonomic conception of botany, parterres had to be illustrated with a geometric layout and spatial distribution, the largest possible part of families, genera and species; without pharmacologically rejecting the important ones, but not turning them into the centre of the research and of the occupation of garden space.

Thus, the modern botanical gardens of the nineteenth century required an important investment in the building of infrastructures dedicated to the cultivation of plants not suitable for the local climate or soil, like shade houses, hot houses, greenhouses, etc. In the Valencian case, all this would have to wait a few years, because the city, the University and even Lorente (sentenced to death by the French occupiers) first overcame the consequences of the war brigs and then those of the liberal revolution. The recovery and the construction plan of the new infrastructures will mainly be carried out during the long term of Josep Pizcueta i Donday (1792-1870) as director, which lasted from 1829 until 1863, period during which the garden, undoubtedly, reached its golden age. You can find how the story continues until the present time at the University of Valencia Botanical Garden website.

[Image 6: current picture of the Botanical Garden of the University of Valencia]

To know more:

- Manuel Costa, Jaime Güemes (ed.), El Jardí Botànic de la Universitat de València. Valencia, University of Valencia, 2001.

- Josep M. Camarasa i Jesús I. Català, Els nostres naturalistes. Valencia, University of Valencia, 2007.

- José M. López Piñero, La escuela botánica valenciana del Renacimiento. Valencia, Valencian Culture Council, 2010.

José Pardo-Tomás

Milà i Fontanals Institution, Barcelona

Higher Council of Scientific Research

Personatges i espais de ciència (‘Science characters and spaces’) is a project of the Unit of Scientific Culture and Innovation of the University of Valencia, with the collaboration of the “López Piñero” Institute of History of Medicine and Science and with the support of the Spanish Foundation for Science and Technology and the Ministry of Economy, Industry and Competitiveness.

.jpg)