Through the looking glass. Obesity readings: Medicine, art and society.

Palau de Cerveró. Sales Lluís Alcanyís i Manuela Solís.

As a means of expression, our body projects our image into society and, as a vital structure, it gives information on our health. Through these two elements, obesity is explained as a global phenomenon, not only for its geographic reach and epidemiological dimensions but also for its scientific, financial, social, cultural, ideological, political, legal and health-related implications. The exhibition includes a number of scientific and historic data and tables, testimonials, documents, audiovisual materials and works by contemporary artists, offering visitors tools for reflection and discussion about one of the most characteristic phenomena in today’s society.

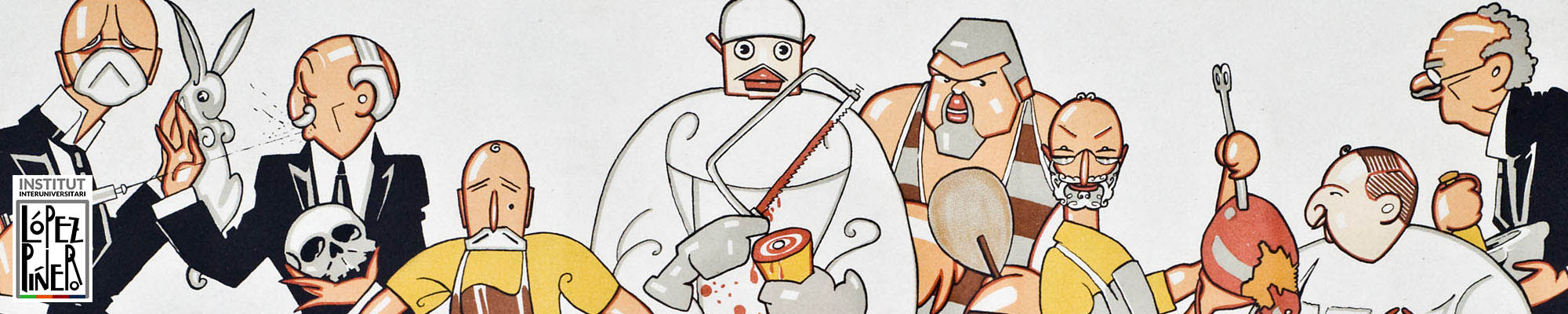

Mass culture stereotypes and obesity images in the press -as reflections of beliefs, attitudes and social values- provide us with contrasts that take us from a figure of the obese positively valued in classical times for its association with health, wealth, social status, physical attractiveness, strength and fertility to the current view, that of a joyous, affable person but also a lazy, clumsy, greedy and funny one, which reinforces the social stigma.

Estíbaliz Sábada, My way (2), 1999. Video, 3’. Artist’s collection

As a result of the many thematic implications of obesity, the project has been structured into three blocks: 1) medical history perspective, 2) social and cultural image, and 3) artistic depiction of obesity, the three of them remaining interwoven throughout the exhibition.

The exhibition starts with a quote by J. George Harrar which addresses the discovery of the calorie as the unit of measurement of nutrition. The starting point of the so-called obesity crisis of today’s society can be tracked down to the demographic, epidemiological, nutritional and dietary transitions of the late 18th century and the 19th century. This analysis helps viewers understand the scientific discourse underpinning current theories and treatments: studies on immediate principles, proteins, fats and carbohydrates; the shift from hunger and malnutrition to overfeeding and excess, the prestigious Mediterranean diet, etc.

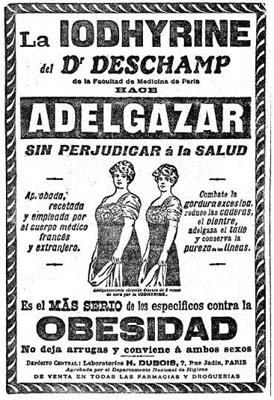

The review of social discourses on the subject covers different stances: the scientific-medical view, which considers obesity to be a disease (today, an epidemic) and a public health issue; body cult, sometimes based on dangerous radical anti-obesity (anorexia, bulimia); the activist discourse for acceptance and respect of obesity; or reporting “biopolitics” or “biopower” as signs of citizen control (health authorities, advertising, etc.)

|

|

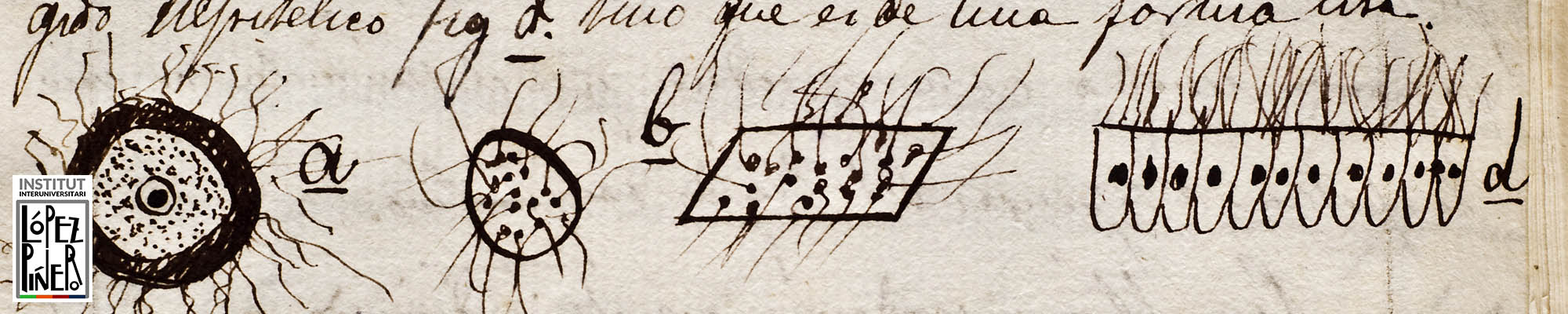

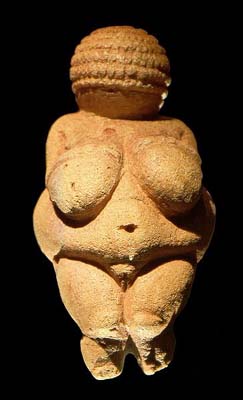

| Venus of Willendorf, 20.000 B.C., Upper Palaeolithic, Danube Valley | Advert published on “La Vanguardia”, 1914 |

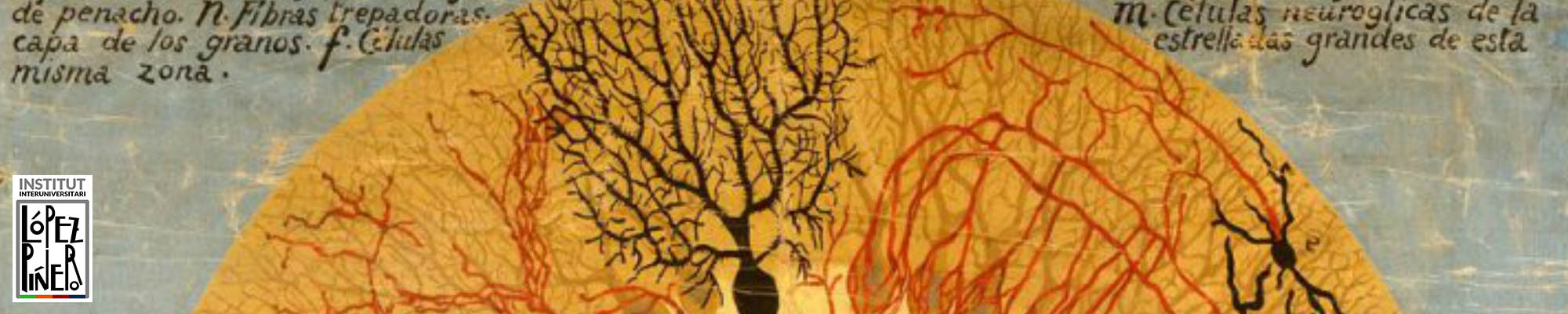

Within our identity map, artists have represented obesity as the looking glass of society and its tensions and conflicts, transferring the figure of the obese to the world of power and affluence, eroticism, sickness, deformation or good health. A review of Rubens’ paintings, of court portraits, of Carreños' monsters, of the images of Palaeolithic Venuses or the popular postcards of the first half of the 20th century so seem to confirm.

Now, new socio-political and gender attitudes have come to transform the depiction of the obese body within a transgressing iconographic territory. And so the photographs taken by Ariane López-Huici –mostly of women– rescue the naked beauty of imperfections. And Rogelio López Cuenca questions symbols and stereotypes from the falseness of advertising in Droits de homme. Puns and wordplay about appearances around us and diet study are Rosalía Banet’s critical vehicle to create her Disease-dispensing machine. But this type of rituals also lead us to Antoni Miralda’s creative work, in which food on a table is not the representation of a basic need but a reason for socialising and for cultural development. The reification of the body and appearance is internalised as a personal experience by artists Estíbaliz Sádaba, in her video My way, and Mac Diego, whose naked image is manipulated through the eyes of other artists.

In sum, the aim of the project is not to indoctrinate or lay down “good behaviour” rules and guidelines but to foster discussion, analysis and reflection about obesity.

|

| Food balance wheel |

|

| Anonymous, poster advertising a fairground show |