The Kingdom of Valencia had reached an enviable economic prosperity during the fifteenth century. From the agricultural perspective, the products dedicated to exports were numerous: the sugar —the quintessentially sweetener, between the kitchen and the medicine, extracted from the giant cane planted in the coastal plains, the wine —basic in diet—, saffron or wools, among others. But also the production of fabrics had prospered and had sought expansion in the European market; drapers, weavers, dyers and woolmen were legion in the medieval Valencian kingdom, very particularly in the capital and in the Comtat region.

The merchant ships from all over the continent came to rest in the ports of the capital and also in smaller ones. Valencia was a cosmopolitan city where travellers admired in amazement all the ostentation and magnificence of the palaces, parties, and the atmosphere of frenzied activity that reigned in the city. As Juan Vicente García Marsilla and Teresa Izquierdo have shown, the city of Valencia in the fifteenth century was a space in which large scale works were constantly proliferating: Quart towers, shipyards, several bridges, the Miquelet, the Cathedral’s Chapter Hall, the Royal Palace, the Palace of the Generalitat, Santa Caterina, the extension of Sant Esteve, the Innocents Hospital... In 1498 the new Silk Exchange had been completed; Pere Compte had bequeathed the future one of the most emblematic buildings in the city, with the closing of the century, and in the year that would be a hinge in the educational progress of the city and the kingdom. After all, a lavish beautification program had been developed in the city; the economic power of the city had to be translated into the harmonious and sparkling aspect of architecture and urbanism.

The city exerted a great appeal on the population of the rest of the kingdom, who assiduously migrated from its towns, especially when the crisis situations thus demanded it. But also people from all over, rich and honourable; technically well-trained, like what we would call “engineers” today, builders, watchmakers, doctors and surgeons, clerics, there were people from Germany, France, Italy, England, Flanders... In Valencia the slave shipments were incessant: Tatars, Slavs, African Blacks, Maghrebies... In short, Valencia was a cosmopolitan and multi-ethnic capital.

In addition, the literary life of the capital and, of course, of the kingdom, was abundant. Joanot Martorell, Ausiàs March, Jaume Roig, Joan Roís de Corella, Jaume Gassull... The list of writers of the golden age is brilliant. But it is also clear that there was a reader audience who was anxiously awaiting new publications. In 1474, Les trobes en lahors de la Verge Maria was printed in Valencia, it was the first text in Catalan printed in the movable-type printing press. The printing industry would soon become a lucrative business.

Now, the successive monarchs of the century, Alfonso the Magnanimous, Joan II and Ferdinand the Catholic, had squeezed the Valencian kingdom coffers to defray their often crazy military endeavours they had launched one after the other. And the economic situation was not always optimal.

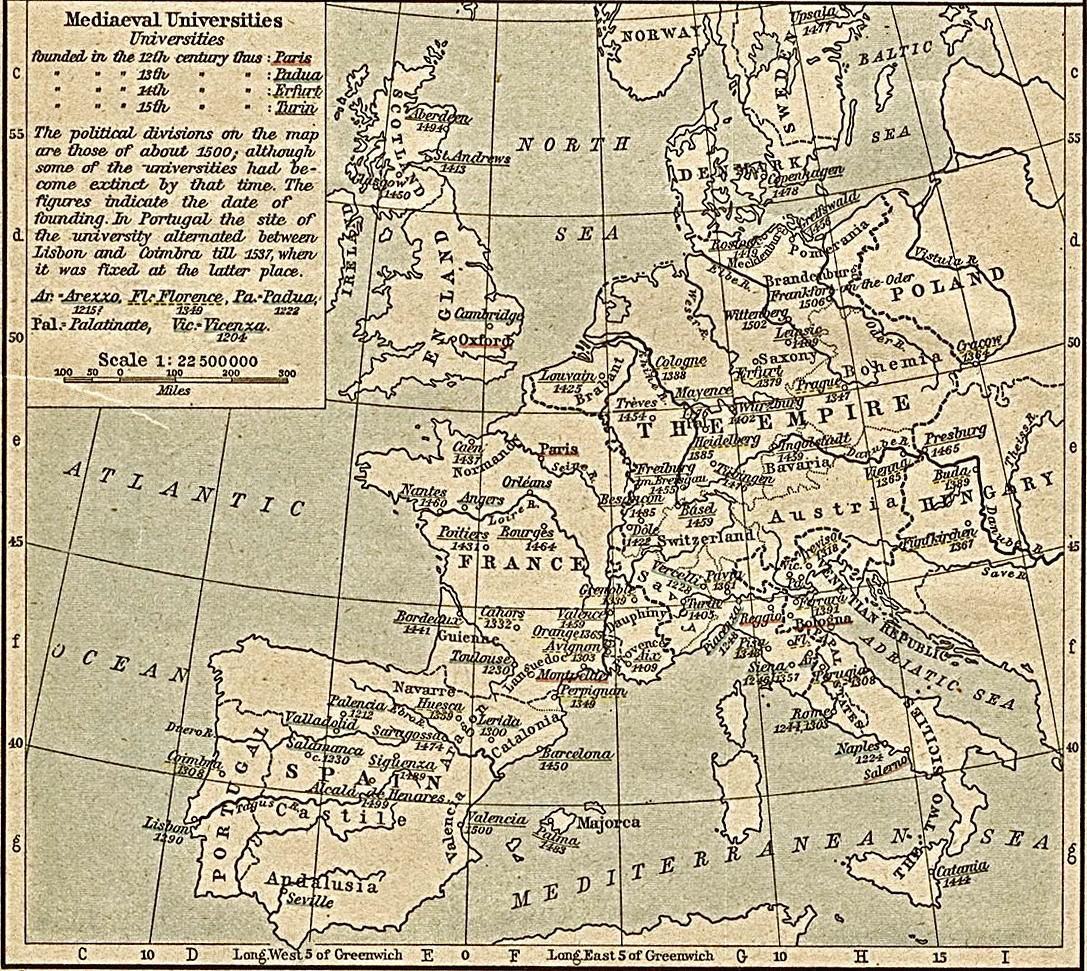

During that period Valencia had been the authentic capital of the Crown of Aragon, also the capital of knowledge. However, the birth of the General Study was quite late, if we observe that tens of universities existed all over European geography in the dawn of modern times. The one of Valencia would be the product of several convergent forces, and a long educational tradition.

Medieval universities map. Source: Vikipèdia

Soon after the conquest of the city of Valencia, the first schools began to appear. James I had wanted to endow them with the university rank. Innocent IV made a bull concession to build a General Study. However, for reasons that have never been fully clarified, the Furs opted for an open model of education, a freedom that allowed opening grammar and other arts schools, anywhere in the city. The proliferation and dispersion of centres, with more or less entity, some of private initiative and others of the municipal council, who taught grammar, surgery —this with great fortune and prestige—, ethics or theology were a reality during all the late Middle Ages, particularly in the fifteenth century, and although the juries of the city made every effort to unify them in a single centre, in 1412 they did not succeed. They were established in premises near the church of Sant Llorenç, although the freedom of regional education allowed the continuity of schools in other places. Therefore, the process was only accelerated in the last decade of the four hundred. In 1492, so remarkable for other well-known events, it was already openly spoken about the creation of the Study. The result of these efforts was the purchase from Isabel De Saranyó, April 1, 1493, of a house with gardens and patios that would become the headquarters of the University: the building of the Nau Street. But in August 15, 1498, at a meeting of the General Council, the remodelling of the study house was agreed, as well as drafting new regulations and requesting approval for them. The statutes that regulate the operation were then created, and the need for a papal bull was shown. And here the city was fortunate that the mitre was in the possession of an illustrious Valencian: Roderic de Borja, Pope Alexander VI. The note sent by the jury to the pope through Canon Joan de Vera says:

“The Prelate Sanctity will plead for giving and granting apostolic bull and grace by virtue of which the city of Valencia to be one of the main and populous in the world, and its Sanctity born there, set up a General Study”.

On January 23, 1501, Pope Alexander VI issued the bull Inter ceteras felicitates, a littera solemnis, culminating the aspirations of the Valencian authorities. The bull, translated from Latin, says things like:

“Among other blessings that in this ephemeral life the mortal man can obtain through the grace of God, we must consider among the most valuable which through the constant study leads to the pearl of knowledge. It opens a way to live wisely and happily, and with its excellences it makes the learned man extraordinarily superior to the ignorant. It favours and helps the clear understanding of the world’s mysteries; it dignifies ignobles and strangers; not only does it teach the best way to govern the public affairs, but also all the virtues; it shows the knowledge of things both divine and human; protects the orthodox faith as a firm defence against the barbarity of infidel beings and the perseverance of the perverse heretics (...).

The community of the favourite children of the city of Valencia has just submitted a request stating that if in this city, that is the kingdom’s head town and is insigne and noble among the cities of those areas, and towards which numerous people from all over the world meet, clergymen and lay people, florists, a general study in which all the licit faculties could be taught, many people from that city and kingdom and other parts would be pleasantly dedicated to the study and would be scholars, and this would extraordinarily result not only in honour and prestige of the city and the government and the utility of the public affairs but also in the salvation of souls”.

The words in the document are quite eloquent. A city like Valencia could no longer be without a university. We must place ourselves on the historical scene in the transit of the Middle Ages, in crisis for some time, until modern times; moment of the configuration of the absolutist states. The Hispanic monarchy, not only of the Crown of Aragon, needed well-formed cadre leaders. A new taxation, a large permanent army and a modern bureaucracy demanded a handful of men with higher education. King Ferdinand the Catholic fixed it with the privilege of February 2, 1502, with which he ratified the university character of the new institution. Thus, the General Study was officially opened on October 13, 1502 with prerogatives and distinctions equivalent to those of the universities of Rome, Bologna, Salamanca and Lleida. Urban authorities, including members of the nobility, had finally achieved it, and proudly exhibited it as a success. That had surely helped them, that is, only distinguished people could afford the expenses of training their children many kilometers from home, and consequently they returned to occupy the most important places of the leaders, it was untenable. The 1499 constitution expressed it eloquently: “many people of the present city are constrained to go outside it to seek general studies and faculties of arts and sciences”. After all, it was an old argument already used two centuries before by James II, when he founded in 1300 the General Study of Lleida, the first university of the Crown of Aragon: his subjects could not study beyond the borders of his crown.

The University of Valencia was born under the orbit of the municipal power and was closely dependent of it throughout the regional law period, as the Council was its sponsor and financial backer of its expenses. Unlike universities such as the ones of Salamanca or Valladolid, where professors, doctors and students played a leading role in the choice of university professors and rector, and decided on notable issues, in Valencia, the authorities decided everything. Even overruling royal and ecclesiastical interests.

Little by little, the constitutions that organised the internal life of the institution were outlined. The governing figures that governed it; the chancellor —figure that always belonged to the bishop; the rector, with an election totally dependent on the municipality, an institution that is increasingly decisive and with more power in the control of the education community; the civil servants, such as janitor, prompter, regent, waiter, etc.—. The various faculties were organised and chairs were divided and provided: Poetry and Oratory, Lorenzo Valla, inside the Grammar and Latin studies (progressively expanded to Greek, Rhetoric, History, Prosody); the Faculty of Arts (with Logic, Natural Philosophy, Súmulas, Questions, Philosophy, Mathematics and Astrology); the conspicuous Faculty of Medicine, where three chairs were stablished throughout the century: the first one, dedicated to the principles of medicine, the second one, to Simples and Anatomy, and the third one, the practice from the books of Galen; the Faculty of Theology (with the chairs Nominalista, Escot, Sant Tomàs and many other later on); and the Faculty of Law (basically Civil and Canonical).

Certainly, the first years of the distinguished institution were quite complicated. From 1518 to 1519, the University remained closed by the plague, and in 1522 the studies had to be suspended as a result of the Rebellion of the Germanies and the economic difficulties that made it impossible to pay the teachers’ salaries. Those were grey years. Rectors were annually chosen by a system of lots. Febrer Romaguera named these first directors “dark lawyers”, since they were individuals engaged in their work as jurists, who were little involved in the management of the centre, with which they only had ephemeral contact. The consequence was slackness and a bad performance, particularly for the patrimonialisation of budgetary, statutory and educational control, with serious distortions in the functioning of the institution. Not even the firm will of the city’s juries to change the wrong course and the appointment of rectors with more continuity, incorporating non-jurists, reversed the situation. It would be necessary to wait until 1525, when there was a change of direction. The Municipal Council decided to take from the Sorbonne a well-known theologian, a prestigious one, as new rector, the Valencian Joan Llorenç de Salaya. He would mark with his personality the evolution of the university for more than a quarter of a century, as he became the first perpetual rector. It was an extraordinarily complex time, in which Salaya ideologically marked the course of the Study as well as some important religious and political controversies, since he paved the way for religious orthodoxy and the interests of the patricians of the city. The university struggled between maintaining a spirit with medieval postulates, with the predominance of nominalism, theology and arts, and avicennism in medicine, or joining the humanist currents. But these questions exceed the purposes of this article.

Whether it was due to the economic, demographic and political prosperity achieved by the city at the end of medieval times, or because of the political situation and the drive given by the leaders of the moment, added to the fact that the papal sole was occupied by a distinguished Valencian, all this made it possible to take advantage of it for the creation of a crucial institution in the history of the Valencian Country. As Ferran Garcia-Oliver said in the edition of the papal bull: “It is almost inevitable to consider the creation of the Valencian University the splendid conclusion of a glorious century”.

Carmel Ferragud (“López Piñero” Institute of History of Medicine and Science)

Marialuz López Terrada (Ingenio, CSIC-UPV)

Personatges i espais de ciència (‘Science characters and spaces’) is a project of the Unit of Scientific Culture and Innovation of the University of Valencia, with the collaboration of the “López Piñero”Institute of History of Medicine and Science and with the support of the Spanish Foundation for Science and Technology.