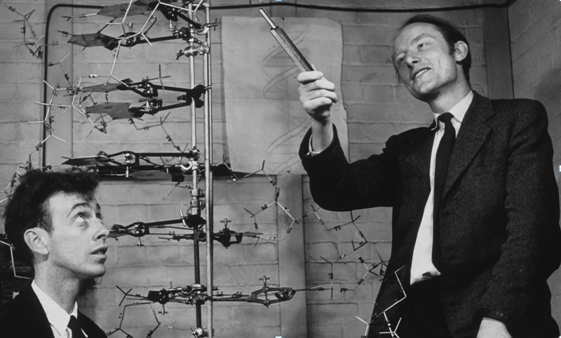

Science has a very tempestuous relationship with its production space. It aspires to provide universal truths that, nevertheless, must be obtained in a specific place and time. This desire for universality is reflected in the scientific articles, which hardly report the spatial and geographical characteristics of laboratories. For example, in the famous article by James Watson and Francis Crick published in 1953 in Nature magazine, which contains the famous proposal of the DNA molecule, there is hardly any mention of the sites where empirical data were obtained and where the famous three-dimensional models were designed. No detail is described of the famous Cavendish Laboratory of Cambridge University, where the authors of the article worked or of King's College in London, where Rosalind Franklin took his famous X-ray diffraction images. Could these famous researches have taken place anywhere else? This is the impression you get when reading this text, just as it happens in so many other science articles. Everything indicates that the spaces of science do not matter. As with the use of impersonal verbs, which seems to blur the existence of specific people behind the investigations, the conventions of scientific language make geographic and spatial peculiarities disappear. If, in order to transform the investigations to be objective, the subject is eliminated, to make them universal it is necessary to make the space context invisible. Thus, through these theoretical resources, laboratories are transformed into placeless places (literally places without place).

And yet the studies on science of the last decades have stated the great importance of the space environment and the geographical context in the production of knowledge. “Give me a lab and I’ll move the world”, said Bruno Latour in one of his provocative articles, with a title that parodies the famous sentence attributed to Archimedes. Latour, like other people who investigate science in action, has been asked about the processes that transform laboratories into spaces for the creation of data of universal validity. According to Latour, together with the invisibility of the spaces, the laboratories must properly manage the rules of admission and the tensions between public and private science. In order to work with discipline, the doors of the laboratories must be closed to the public. Only those who can prove certain disciplinary knowledge are allowed to enter. But to be able to “move the world” (or transform it, as is the case), knowledge must circulate outside the laboratory, attract the interest of external people and promote new social and cultural practices that are significant. Scientific articles in specialised journals are insufficient in this regard. The movement of people, objects and practices is required.

Once the scientific mythology that surrounds them is overcome, laboratories seem to be characterised by complex tensions. They can only express their characteristics through contradictory terms: invisible spaces, but with strong access restrictions, and at the same time permeable enough for the circulation of knowledge and practices that must allow their social legitimacy. It seems laboratories must segregate and connect at the same time to be able to produce truths with an aspiration of universality.

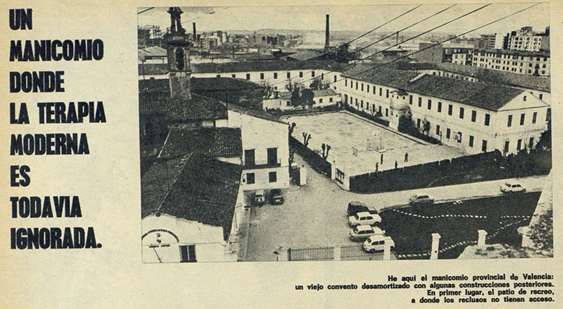

Laboratories, like other social spaces, are loaded with several layers of meaning. Its architecture can represent idealised images of science (for example, a relationship between theory and practice). At the same time, their particular form conditions the ideas that occur there. Michel Foucault used the expression “heterotopia” to refer to the singularities shared by laboratories with other types of spaces such as barracks, asylums, museums, libraries, monasteries or prisons. These are areas that allow segregation and discipline, but always maintaining its connection with society, without which their productions make no sense. There are several social systems and cultural representations in heterotopies, according to the point of view of visitors or residents, students or teachers, prisoners or prison officers. Each space has its own division of labour, rules of sociability and moral economy, with particular ways of attributing authorships and rewards. There may be people who carry out crucial functions, but they are hardly mentioned in scientific publications because of the accepted conventions.

But experiments are not only held in laboratories, nor all the activity that is developed there is experimental. There are many types of laboratory according to the discipline involved, from physics to molecular biology. The functions that are carried out there, such as research or teaching, are also varied. There are laboratories dedicated to quality control, crime detection or clinical analysis. Others have more to do with the industry, the feeding and the production of goods of consumption.

Not all science is experimental or is exclusively developed in laboratories. Many investigations take place outdoors, with no doors or windows. Examples of this range from research on animal behavior to epidemiology work that seeks to study diseases. These investigations usually designate a space or set of sites that serve as a source of scientific truth (or truth-spots, according to the expression of Thomas F. Gyerin). In these cases the spatial features matter. They must be described in detail to show their representativeness in the subject studied. The circulation of knowledge from one place to another can be more complicated than in the case of laboratories. For example, we can ask to what extent the particularities of the Nordic countries, where the first investigations about acid rain have been performed, can be used to study problems such as those that affected the Ports area in the eighties and nineties of the twentieth century?

Other spaces such as “experimentation farms”, which allow the development of new pesticides, designing fertilizers or testing seeds in new areas, are in an intermediate position between the closed laboratory space and the undisciplined nature. The autopsy rooms, botanical gardens or natural history museums could also be located at this intermediate point. The great diversity of rules of sociability that exist in these spaces of science is obvious. Residents, visitors and object display systems are also varied, which condition glances and readings, without eliminating the creative capacity of audiences.

More unclassifiable are the spaces in which people engaged in mathematics work, where the same space and its abstract representations may be the subject of the investigation. Social representations of space are also central themes of cartography. We know that cartographic divisions report both science and the political ideas of a time. On the other hand, people who work from the field of engineering or architecture do not only intend to study the spaces. They also have to imagine other new ones and perform transformations. Many areas of science, like some of those that are reproduced here, were nothing more than paper plans. Others were carried out, with more or less fortune and fidelity, and disappeared to make way for new buildings. Only a few have become “places of memory”, and have been preserved to perform new symbolic functions during celebrations of all kinds.

Scientific articles do not usually deal with these spatial issues. Nor do they describe the processes that make science universal. It seems to be assumed that, once established in a specific place, the scientific truth acquires the divine qualities of omnipresence and ubiquity. In fact, studies on science have revealed that their circulation involves complex processes. They require methods of calibration and standardisation to make the reproducibility of experiments possible. It also involves the circulation of practical knowledge and highly specialised and disciplined personnel. In short, the circulation of science demands the creation of “immutable mobiles” (specimens, instruments, calibrations, etc.) that travel throughout the world without losing their identity.

In spite of these efforts, when science circulates it is transformed. Movement usually involves slight changes or more or less ample re-formulations, particularly when the know-how confronts host cultures. These circulations are developed on various geographical scales: local, regional, national and global. They can also take place between various disciplines, for example, between physics and medicine, or between mathematics and chemistry. There are also transformations when knowledge circulates between the academic world and the school culture, and give rise to reformulations (school disciplines) that have a life on their own. In each of these cases, the circulation of science takes place within a space of social and cultural forces, under tensions caused by strong imbalances of academic, economic and political power. Often the circulation of science is a product of (or causes) injustices and conflicts. It can also destabilise scientific knowledge and subtract credibility: what is accepted as science in one place can be considered witchcraft in another one (and vice versa). In short, the universality of science is not automatically achieved, but through complicated processes of transport and translation within a social space with strong imbalances.

The circulation of science does not only take place in academic and strongly disciplined territories. It also has to circulate through the public sphere, through points of contact between experts and profane people. This circulation is not unidirectional. Often, it also occurs in the reverse direction in the form of popular knowledge, cross-interest and resistance. In this same sense we should also consider all the different forms of what is currently called “citizen science”. The press is another one of the territories in which this circulation of academic knowledge is produced, through translations, readings and inventions that are also round trip. Even the home environment has been an important space for science. In the eighteenth-century halls many crucial experiments and meetings were developed, with a prominent role for many women who found here fewer access and participation limitations. Most European academies do not allow access to women for much of the twentieth century, sometimes through arguments based on the science of the time. In short, the spaces of science are also conditioned by gender bias and social inequalities of all kinds, both in the past and in the present, as has been reported by a recent issue of Nature magazine in September 2016: http://www.nature.com/news/science-and-inequality-1.20652. The spaces speak of these inequalities, and at the same time they can help to reinforce or mitigate them, both locally (among people) and globally (among territories).

“Science has no homeland.” The sentence is often attributed to Louis Pasteur and is often used to emphasise the universal character of science. The continuation of this speech by the French microbiologist in 1888 is much less well-known: “If science has no homeland, the science man must have one, and this must refer to the influence of his work in the world.” The complete sentence suggests ideas that are more in agreement with the ones mentioned here: the national context in which scientific activity develops itself greatly conditions both the content and the possibilities of success. A brief overview of the Nobel Prize nationalities allows us to quickly verify the inequality of opportunities to carry out quality scientific research by country. The success of scientific works depends on the available resources, as well as on the social valuation of science in each place. Some authors have talked about “national styles” of science, a very debatable concept that would make it possible to distinguish, for example, Japanese science from the North American one. Other authors, on the other hand, have pointed out the importance of science in the construction of the nation-states during the last two centuries, both through the production of knowledge needed for state bureaucracy (for example, cartography, engineering or scientific police) as through the manufacture of collective imaginaries by means of cartographic division, the exaltation of their own nature or the conversion of scientists into heroes of the country through pictures, statues and celebrations.

This brief review indicates that when emphasising more spatial and geographical aspects of science, many scientific myths can be broken. This situation is precisely due to the relationship between science and spaces, as seen in the previous examples. In spite of the aspirations of universality and objectivity, science is not beyond good and evil, it is part of certain societies and cultures, which it modifies in turn, without it being possible to understand scientific activity outside of these circumstances. Studying the spaces allows us to deepen in the characteristics of science that do not usually appear in the works of dissemination.

José Ramón Bertomeu Sánchez, “López Piñero” Institute of History of Medicine and Science

Personatges i espais de ciència (‘Science characters and spaces’) is a project of the Unit of Scientific Culture and Innovation of the University of Valencia, with the collaboration of the “López Piñero” Institute of History of Medicine and Science and with the support of the Spanish Foundation for Science and Technology and the Ministry of Economy, Industry and Competitiveness.