There have been many women who have given a strong drive to numerous activities in history –literature, science, education, art, culture, artisan, peasant, worker, intellectual, etc.– but have had very poor visibility for the rest of humans. It has been a world predominantly revealed from the perspective of men. Throughout the nineteenth century, the different spaces occupied by both men and women are clearly seen; as for those, their fundamental activity will be in the path of public things: work, education, university and politics. The activities of women were primarily restricted to the private sphere, feeding and attention of their children, domestic education, that is, to the tasks that marked the field of maternity as assigned to female gender in their life trajectory. From the second half of the nineteenth century and especially since its last decades that started to change, despite the frequent and intense controversies, and we will see women –although very discreetly at the beginning– will gradually have more presence in some industries and factories.

During the transition from the nineteenth to the twentieth century serious thought was given to how the demands of women in all areas, whether domestic, educational, scientific, cultural, political or labour, would have to be considered. A vision more in line with the one that marked the new time, where women had their own journey, outside the role marked by men, and where they wanted to have full control over aspects as diverse as motherhood, education or political participation was witnessed. In the educational field, despite having an intense debate between the religious model/lay model, from the seventies to the eighties of the nineteenth century, in Europe and mainly in England and France, the path that students will take to obtain first the baccalaureate and later gain access to the University. This process will not culminate until the first years of the twentieth century, when the regulated and normative access of women to higher education will gradually be established in different countries of our continent and where medical studies will be those that will be predominantly chosen.

What happens in Spain and Valencia during this age between centuries? Although there were beginnings in the first decades of the nineteenth century, in the sense of establishing certain higher studies, we must wait for Moyano law (1857) to see how teacher training instituted in normal schools and how he determined the establishment of higher science studies as a separate degree. This will be a significant but not sufficient advance in the path of the general incorporation of women into the university, which will still have to suffer from problems such as requesting official authorisation in the eighties of the nineteenth century to be able to study, which was a requirement for women until 1910, the year in which freedom of registration in the university was already established.

Regarding Valencia and similarly to other Spanish universities towards the end of the Democratic Sixth and coinciding with the First Republic, the first university women begun to enter, which meant that the first female students of our university studied first in the Faculty of Medicine and later in the Faculty of Sciences. It is true that between the academic years ranging from 1874 to 1889 7 women begun superior studies: 1 in sciences and 6 in medicine.

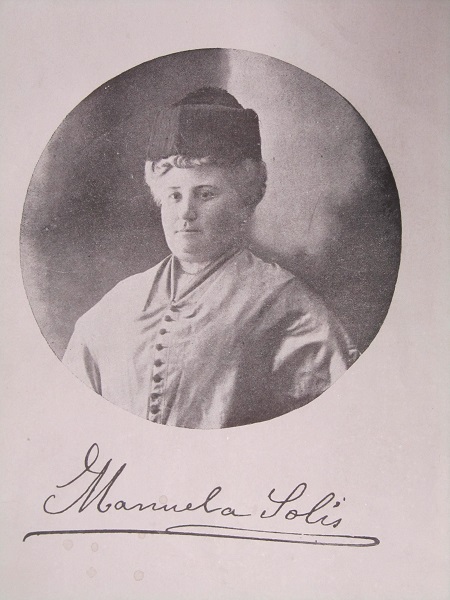

Manuela Solís was born in June 1862 in Valencia and, as stated in the report of the parish priest of San Pedro of Valencia, was the daughter of Prudencio Solís and Manuela de Claràs. Her father was a teacher in the Normal School of the Province of Valencia and she was purposefully involved in the school reforms through various publications and translations, as well as in professional associations or in pedagogical congresses. She also had a brother, León Solis Claràs, doctor, who was also a teacher of the medicine degree. We have, thus, to understand the cultured environment in which the future doctor Solís was educated and how, after the baccalaureate, she finished it in June 1882, requirement she fulfilled with the highest mark and that allowed her, after obtaining the degree, to begin her university studies.

Like other university female students of that time, she chose medicine, which in those final years of the nineteenth century was the career of choice of the female students who completed the baccalaureate in Spain. In the file stating she obtained the bachelor’s degree in Medicine and Surgery, which she started in the academic year 1882-1883 and finished in the 1888-1889 one, the magnificent result of her qualifications is recorded, which in every subject was an A. At the end of these studies and in order to obtain a bachelor’s degree, she underwent several exercises, such as the diagnosis of a tuberculosis patient or the dissection of a corpse, which was the last one and in which she obtained an A. Among the examination board of these exercises we can see the signature, as president, of professor Nicolás Ferrer y Julve, who then taught Surgical Anatomy at the Faculty of Medicine of Valencia. Once obtained the bachelor’s degree, in order to expand her studies she went to the Spanish capital, where she enrolled at the Rubio Institute of the University Hospital of the Princess, institution created in 1852 and where, independently, the Surgical Therapy Institute is created, which was created and directed by doctor Federico Rubio y Galí. This last centre was the first in Spain where ovariectomy, hysterectomy and other interventions were performed and has been considered as the pioneer hospital centre in teaching and assistance and in which new kinds of surgery were performed. We can understand Dr. Solís was in touch with the latest advances in surgery which helped her so much in her career as gynaecologist.

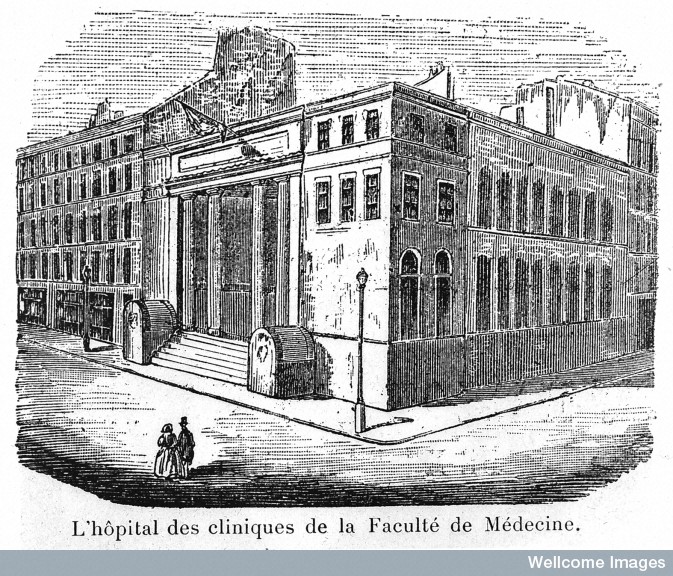

After her stay in the Spanish capital, in order to expand knowledge in her specific training, she went to Paris, where she entered the Birth Clinic of the Medicine Faculty of Paris. There she met the doctors Tarnier, Varnier, Pinard and Pozzi, the first of which gave name to various obstetric instruments such as the Tarnier forceps, the Tarnier basiotrib (which allowed the reduction of the skull and the extraction in cases of dead fetuses in the uterus) and others, as well as conceiving a smaller and cheaper incubator. The second doctor, Henri Vanier, was an obstetrics professor, a student of Pinard and co-author, together with the anatomist Farabeuf, of the well-known treatise Introduction à l’étude clinique et à la pratique des accouchements, on the clinical attention during childbirths. The third one, Dr. Pinard, was another obstetrician who gave a lot of importance to the abdominal exploration of the pregnant woman and, above all, she is known to have invented a monoaural stethoscope in the form of a narrow cup perforated on both sides. And finally, Dr. Pozzi, considered by many the father of French gynaecology, introduced the antisepsis of Lister; he obtained the first chair of Gynaecology at the Faculty of Medicine in Paris, and he designed surgical instruments as well. This explains the solid foundation in the training of the Valencian doctor who would later apply it in her daily practice.

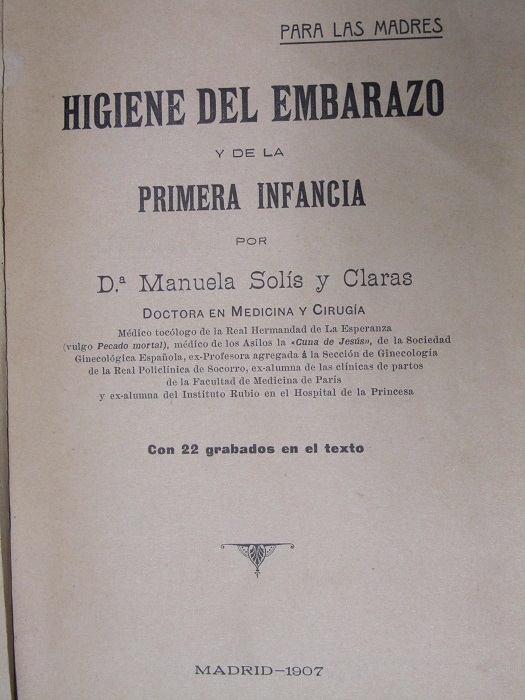

When she returned from the French capital and after her temporary stay in Valencia, where she worked as a gynaecologist with social recognition, she settled in Madrid, where she provided private assistance and clinical care in various charitable and social institutions. This is how the cover of his book Higiene del embarazo y de la primera infancia, published in Madrid, shows the diverse activity she did. In addition to her previously mentioned training in Madrid and Paris she developed a professional work in centres such as the nursing homes Cuna de Jesús, Real Hermandad de la Esperanza and the Real Policlínica de Socorro. Dr. Solís acted as an obstetrician in the second of these institutions, whose full name was Santa y Real Hermandad de María Santísima de la Esperanza y Santo Celo de la Salvación de las Almas, which played a significant role in the care of single women who, without being prostitutes got pregnant. Thus, we see her firm trajectory in favour of women with fewer resources and social problems in the Madrid society in the transition from the nineteenth to the twentieth century.

The years that she lives and works in Madrid, together with her previous stay in Paris, help her to get information as well as gain experience and, as a result, she submits her thesis, El cordón umbilical (‘The umbilical cord’), in 1905. Prior to its submission, she studied the corresponding doctorate subjects Critical History of Medicine, Chemical Analysis and specifically analysis of poisons, Anthropology and Extension of public hygiene. Having passed all this academic process, she obtained the doctor’s degree on October 18, 1905 with an A. By carefully reading her thesis, which can be found in the National Historical Archive, in the first lines the Valencian doctor emphasises the importance of knowing the cord, both anatomically and physiologically as well as its alterations, due to the implication of this subject in the daily practice of obstetrics. Next, she divides the work into two parts: on the one hand, the aspects related to the normal situation of this anatomical element and, on the other one, speaks of the abnormal and pathological aspects.

Through the pages of the first part, which occupy a greater extent, she describes with some detail aspects of anatomy and physiology such as: definition, origin and development, description of the anatomical and physiological relationship with its surroundings, such as the maternal placenta or the forming body of the future child, and the different insertion of the cord in the placenta according to different authors. In this part she also describes the different length that he or she may have (from 0.02 m at 2 months old at 0.50 m at the time of birth) and mentions Alexandre Lacassagne (doctor and French criminologist who founded the School of Criminology in Lyon), given the importance of length in order to offer useful information in legal medicine. Other aspects discussed there are related to the structure, consistency and physical characteristics. Finally, in the same first section, it shows a casuistry of different authors with several observations about the relationship between the cord breaking and the position of the mother. In the second part of the thesis she first speaks of the anomalies: insertion, length, caliber, direction, shape. Next she explains the pathological conditions such as adhesions or obstruction of the umbilical circulation. Finally, her conclusions end the doctoral work.

Because of her career, both scientific and social, she was not only recognised by professional societies –she was elected to be a member of the Spanish Society of Gynaecology in 1906– but her work was also highlighted in newspapers such as ABC or El Pueblo. Specifically in the latter, on July 1908, a central column on the first page was dedicated to her to take taking a tour on her career, highlighting her activity in Paris to receive training:

“...In the capital of France, the distinguished lady was the subject of the greatest attention and of an extraordinary interest on the part of her teachers and colleagues, not because she was the first Spanish woman to be devoted to scientific studies in Paris, but rather due to her great intelligence and the solid instruction she possessed...”

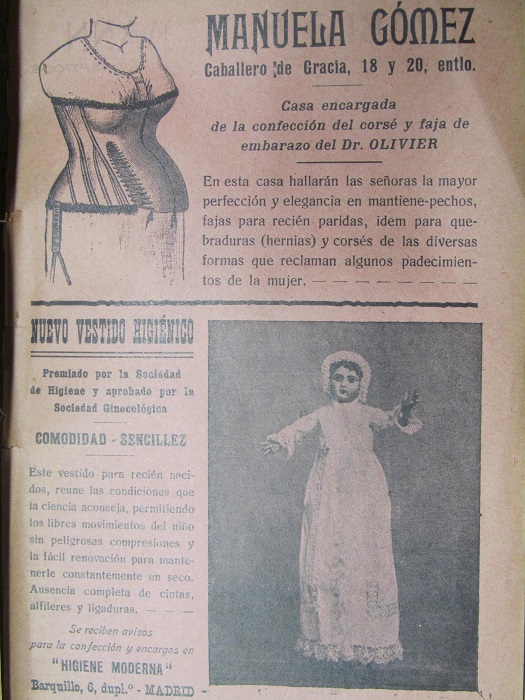

As a result of the work carried out in the various clinical activities, both public and private, and with the main objective of teaching mothers, she wrote the book Higiene del embarazo y de la primera infancia (‘Hygiene of pregnancy and early childhood’), which appeared in 1908 in Madrid and had a preface written by Santiago Ramón y Cajal, who had been her teacher and where he emphasised her professional and scientific career, putting it as a role model. In a time of consolidation of the hygienist movement and also of the significant role that education in large layers of the population was having in Spain, the progressive incorporation of women into work and university studies marked an encouraging beginning of the twentieth century. The book by Dr. Solís deals with aspects that specifically happen during the months of pregnancy and those referring to children, emphasising –and as it is expressed in the first pages– that her interest is to disseminate basic and easy to understand knowledge so that the woman knows how to take care of her own health and that of the child to be born.

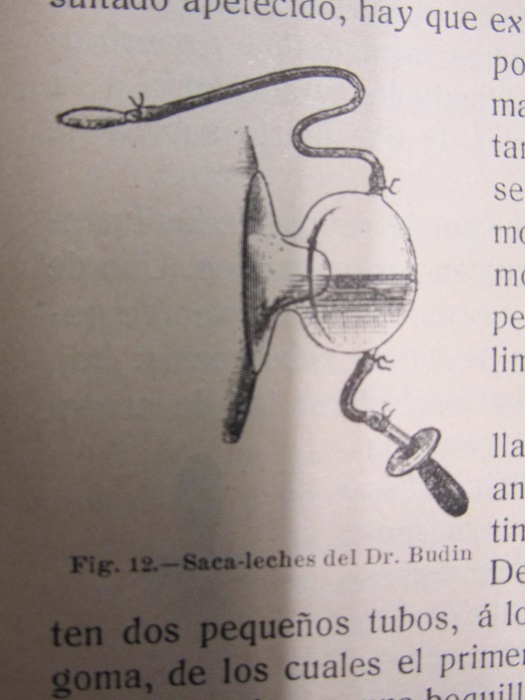

The publication is structured in two parts: the first one primarily aimed at talking about the health of the pregnant woman, initially gives general ideas such as duration of pregnancy, observable changes and even pregnancies that are not. It recommends the specific observation of a professional, as well as commenting on the various elements that may be involved in the mother’s body such as food, clothing, exercise or travel. In the food section, she already gave her opinion on how unjustified it was to recommend pregnant women to eat for two and highlighted the risks of following an advice so widespread among the population. Further ahead she talks about the slight alterations that may appear during these months and the advice she gives to solve them. A few weeks before childbirth, she talks about the convenience of intravaginal irrigation in order to keep clean the channel where the newborn will go through. Finally, she mentions how the future mother should be prepared in the moments close to the delivery and ends up addressing the issue of breastfeeding, where the recommendation in those years and for a long time was that the newborn was put on the breast of the mother 4-6 hours after birth. Regarding other recommendations on breastfeeding in a large majority of aspects, they have survived in time and specifically in terms of the duration of breastfeeding, like it is done nowadays; Dr. Solis says the baby does not need any other food during the first 6 or 7 months of life.

The second part is devoted to the first stage of childhood from a hygienic point of view. It addresses aspects such as first aid during the first hours, what to do the first days, focusing on the most basic childcare elements to take care of a baby in the first stage. Finally, it deals with vaccines. In this chapter she talks about the vaccine against the smallpox, which was the only one that was systematically administered since the previous century. In the first pages she refers to the benefits and advantages of receiving it, although mentioning that there was also a part of the population that were not sure about its administration and attributed many problems and complications to it that in many cases were not proved. She also talks about the different types of vaccine: on the one hand, the human or Jennerian, which was applied arm to arm and used for many years (it is the one used by the physician Balmis, from Alicante, in his great philanthropic expedition to the American countries at the beginning of the nineteenth century); on the other hand, the animal vaccine, veal lymph, more current and more available was extracted thanks to the existence in many countries of the vaccination institutes. The Valencian doctor continues to explain other aspects of the same chapter such as that vaccinations should start around 3-4 months old and that inoculations should be three in each arm, based on the fact that at this time one thought that, the greater the number of pustules, the more immunity was generated. And regarding remedies in the face of discomfort or pruritus in the area around the pustule, she talks about applying rice powder (which has been used since ancient times in many skin problems), and even, in major inflammations, put cataplasms of stalk or rice flour starch.

Manuela Solís i Claràs died in 1910, after an intense and fruitful personal and professional task, the year that marked a significant event, since from that date onwards, the law and equality between women and men to access all educational levels was legally established in Spain. After more than a hundred years of the presence of Dr. Manuela Solís among us, her work, as well as reflecting her task in multiple publications, remains relevant. Thus, a didactic project, Manuela Solis Clarás. Una mujer luchadora ante las adversidades (‘a woman struggling against adversities’), was done at the Universidad Cardenal Herrera-CEU in 2013. In this project, several sessions take place in the classroom that essentially deal with education between the nineteenth and twenty-first centuries, the role of women and access to studies and a vision of contemporary Spain. Through the figure of Manuela Solís, there is debate on the most important facts of her life and how they have changed educational and equality aspects between men and women during the last century. We must also say that, as a recent acknowledgment, and necessary since she was the first female Valencian doctor, the current municipal corporation of Valencia has agreed to name a street after her in Valencia.

Joan Lloret

Institute of History of Medicine and Science, University of Valencia

www.uv.es/ihmc

Suggested readings:

- Álvarez Ricart, M. Del Carmen. La mujer como profesional de la medicina en la España del siglo XIX. Barcelona, Ed. Anthropos, 1988.

- Flecha, C. Las primeras universitarias en España, 1872-1910. Madrid, Narcea de Ediciones, 1996.

Personatges i espais de ciència (‘Science characters and spaces’) is a project of the Unit of Scientific Culture and Innovation of the University of Valencia, with the collaboration of the “López Piñero” and with the support of the Spanish Foundation for Science and Technology and the Ministry of Economy, Industry and Competitiveness.