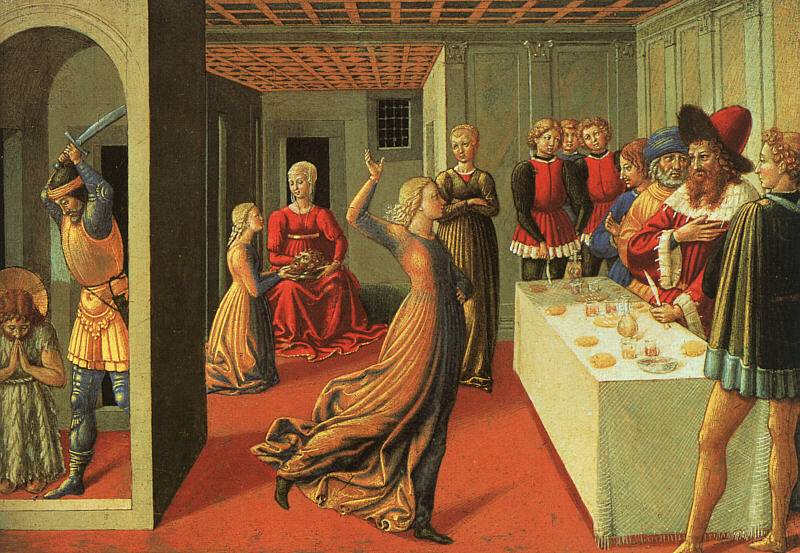

Medieval history is written around men, never around women. We analyse the role of women in this period

17 june 2016

In history, women have been pushed into the background and in almost all history books they are not even named as significant figures of any epoch. If they are, it is usually due to their connection with male referents, that is, due to being “someone’s daughter”, “someone’s wife”, “someone’s descendant”, “someone’s mother”, etc.

There are more women known for being “someone’s widow” that assume the main role. Most stories that have reached our time on widowed women show them as characters that decide to take control of their life: they normally belong to the wealthy class and they decide, after the death of their husbands, that they are going to take control of their property. This is what the Duchess of Gandia, María Enríquez, did. After the death of her second husband –Juan de Borja– and with the requirement from her father-in-law to marry again, she decided to stay a widow and to take charge of the duchy that later would have to transfer to her son. This is how Frederic Aparisi tells it in this article of the Grup Harca.

In this story we see how the woman is the main character due to the lack of a male figure, we see how she finally does the work traditionally assumed by a man. She has to take charge of the duchy until her son can substitute her: the woman is a “patch” available until a new man takes again the control of the family. Or at least this is how we have been told. The lack of women in written sources with which researchers have worked until now leaves us a very dim picture of medieval women. We only know them through ecclesiastical documents, which represent them in two ways: as Eve or as the Virgin Mary, that is, as a sinner or as pure and chaste.

Going back to the example of the Duchess of Gandia, María Enríquez (which illustrates this new), we observe how she had enough knowledge to handle the familiar properties but she was not allowed to take that role unless there was not man in the house. In the few occasions when women took control, they did not make decisions in an independent way, but they had the supervision of the closest relatives and friends of the man. We see again how men are always present, since medieval history is written from their position and acts, never from the perspective of women.

Published by: Inés Luján