|

|

|

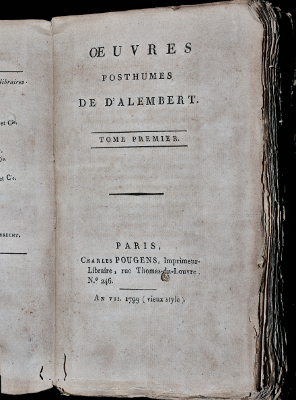

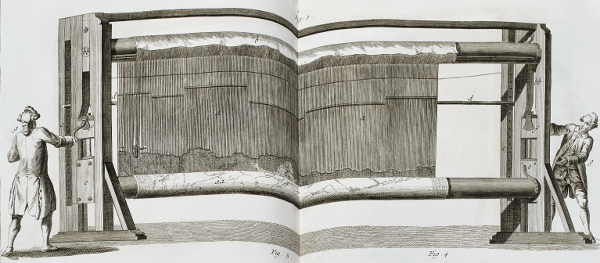

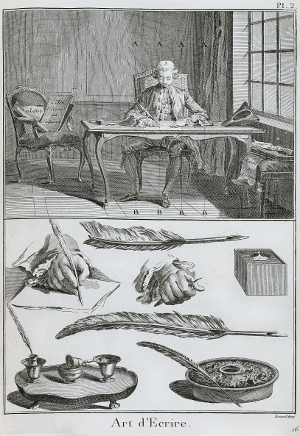

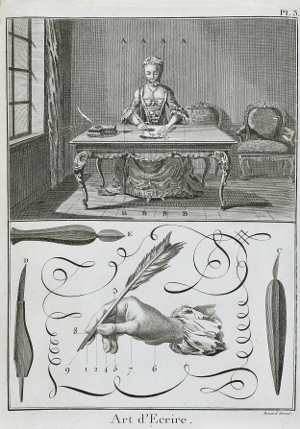

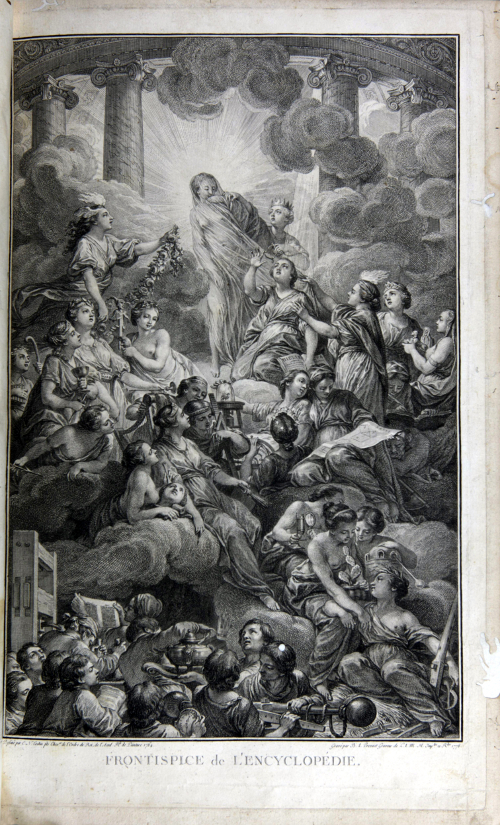

The Encyclopédie (1751-1772) by Diderot and D’ Alembert is a huge milestone in the history of European publications. No previous book had ever given rise to so many mixed feelings. The Encyclopédie was an attempt by some of the most renowned academics of the time to systematise knowledge and spread the principles of universality, truth, humanity, autonomy, reason and laicism.

|

|

The first edition of the Encyclopaedia published by Diderot and D’ Alembert in Paris between 1751 and 1772 was intended to systematise, in alphabetical order, the enormous body of knowledge circulating in 18th century Europe. It was as praiseworthy an endeavour as its second goal, namely to democratise knowledge and make it accessible to everybody. But this idea was somewhat hindered. Diderot's sumptuous edition was printed as folio-sized pages and sold at a very high price, which caused the book to be limited to the “Republic of Letters”, an elite of intellectuals scattered around Europe. This certainly clashed with the very ideals of a universal Encyclopaedia.

|

|

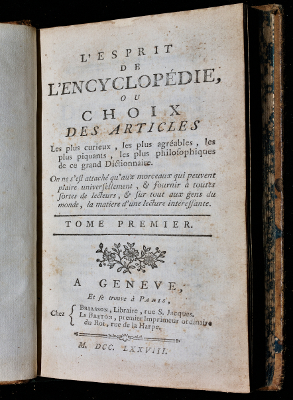

As was the case with other great works by the philosophes, it was mainly the Swiss printers who popularised some of the flagship projects of the Enlightenment, like the Encyclopaedia, quarto editions of it being published in Geneva and Neuchâtel in 1777-1779, and octavos in Lausanne and Bern in 1778-1782. Financial interests prevailed over intellectual ones, which explains the publishing of pirated copies in Lucca and Livorno. 24,000 copies in total were sold out in Europe.

The ’best-seller’ ignited some people’s conscience. In fact, in 1750 the French Council of State banned the printing of the first edition and included it into the list of banned books. In spite of the ban, the first edition was circulated in Spain basically at the Economic Societies of Friends of the Country after being granted a licence for the reading of banned books. This was possible thanks to the more tolerant attitude of the Inquisition at the time, presided by the Valencian philosopher and scholar Felipe Bertrán.

|

|

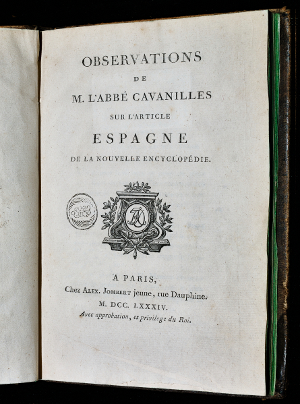

This was not the case with the edition Méthodique (1782-1832) by Panckoucke, a publisher from Paris. Its circulation in Spain gave way to confrontation between a great many figures and institutions like the Council of Castile and the Inquisition. The inclusion of the article “Espagne” by Masson de Morvilliers finally tipped the balance in favour of the ban and censorship of the French encyclopaedia. Taking on a contradictory position, a Valencian character, Cavanilles, was fairly critical in all these dealings. He fist defended the goodness of Spanish culture in response to Masson, but in the end he became the main advocate of Panckoucke and his works in Spain as a result of his correspondence with the Parisian librarian Jean Baptiste Fournier.

|

|

As a publishing project, the Encyclopaedias shook European conscience, as happens today with Wikipedia, and already questioned issues such as copyright, knowledge dissemination, censorship and, ultimately, the moralisation of knowledge.