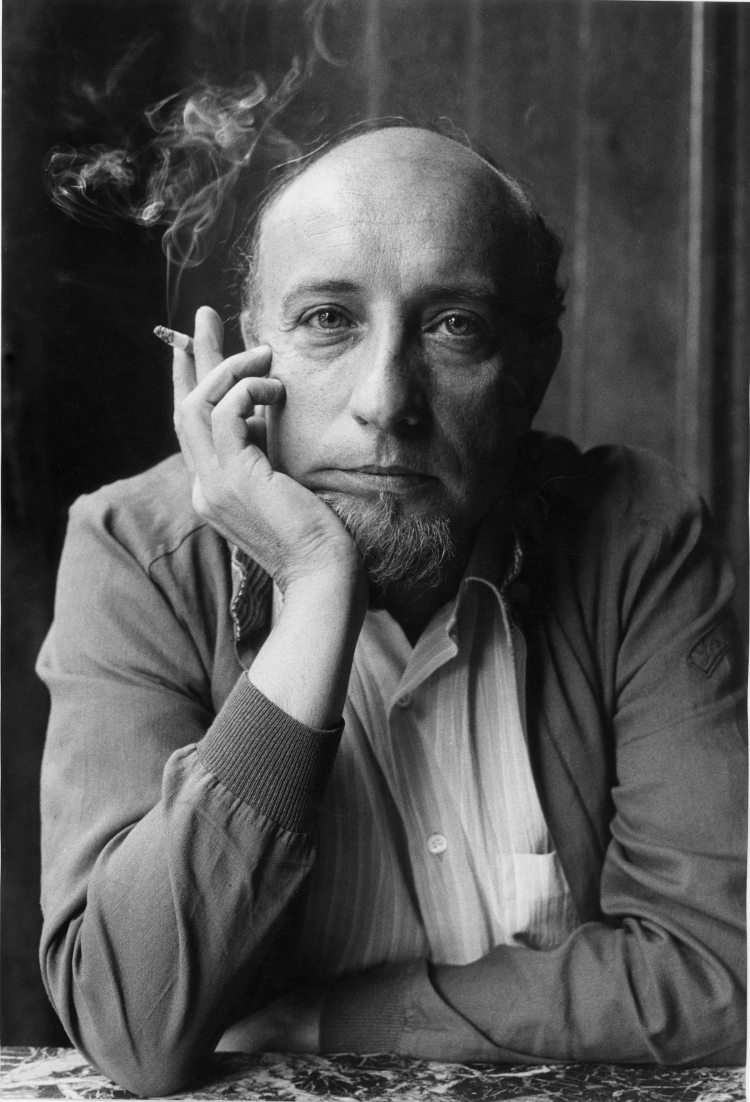

Rafael Alberti, 1981 © Ricardo Martín

The physiognomy of a period takes time to take shape. The present is flow, shock and confusion. The present is each one of the moments or images that each individual lives, without much connection among them, either in a clear order or a tonality. An era takes place when it has already past. Then, you notice this familiar air in what seemed to be singularities, and notice the deep homogeneity that was in the most varied aspects of material life such as hair fashion, the shape of the cars, the aesthetic of the advertisements and the form of the people in the streets. “Whatever happens in the same time period is similar,” said Proust. You pay attention to your daily tasks, get distracted, fall in love, have hobbies, have bad habits, meet with your friends: a few years later, all these stories have a deep biographical unity. Among all these moments and actions in which you did not notices any rupture, they were drawing some of these dividing lines that shape the experience. You live immersed in your time, but you notice it as little as you notice the immense weight of the atmosphere.

Maybe, before photography was invented, it was much more difficult to build this temporal consciousness. There are things that the memory does not preserve. Actually, the memory preserves little information, much lesser that what it could be expected. This is the reason why it is shocking to find yourself in a picture that another person has preserved, or nose about in newspapers of a few years ago. As older cameras did not catch images in movement, the memory does not catch the constant change that is happening in front of our eyes, but it is invisible for them. The present is neither a state nor a place, but a transition. However, we perceive it as a habitable and paused state, our house in time. Any newness becomes an old story in just a few years and for each one of the apparently invariable faces that surround you to become a remnant of disease that they no longer knew were suffering. Nonetheless, it is clear when the face of a younger past is seen again.

Unexpected diseases are so severe that some of the old folk have succumbed to it. The photo album is a strange kingdom where the death and the living are together, and youth seems something generational, like the wardrobe or the haircut. We were all so young in the 1970s and 1980s. Even the elder seemed to be infected with that general youth, or at least not excluded from it. They were not shut down in misanthropy, or in the resentment of not being part of that extended and festive vigour, tendency towards the bewilderment and expectation.

No one can work more with the present than a press photographer. His material is what bursts into, what happens now, what will not be imprisoned a few seconds later. The characters that are portrayed by the photographer stand out because of their momentary game, public relevance that not often will last for long because it tends to be regulated by the speed of politics and style. Suddenly, in the 1970s and 1980s, there were in Spain many stories to tell and photograph, and many young and relevant people. Ricardo Martín was in one of the cores of this long-lasting storm. Ángeles García remembers that she walked with him around Madrid towards some event, disaster, terrorist attack, to one of those shocks that we lived together and were moulding, without us noticing, the physiognomy of a time period that turned out to be out youth.

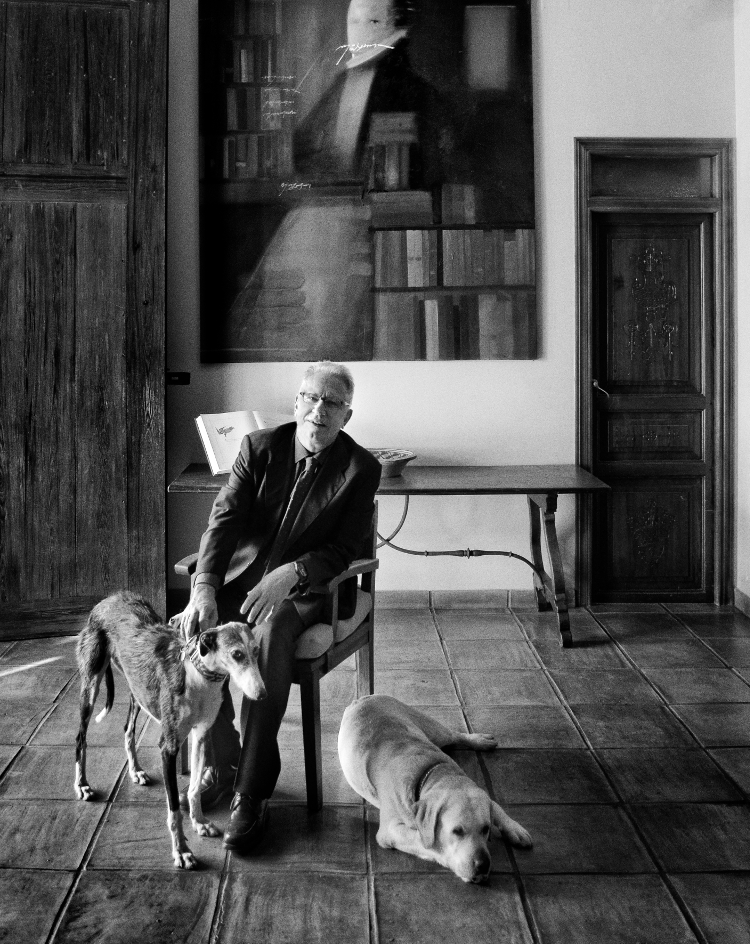

Ricardo usually ran from one place to other taking pictures. Then he ran to the laboratory and the next morning he looked at his photographies in the newspapers, but he saw them disappear in the tones of paper of the following day. Ricardo, raised up among newspapers, had this quick understanding of time, this skill of hunting the moment. But from the beginning or always, there was a sense of time in him, other contemplative intuition of photography. This is something that you can see in his work and in him, when you know him well, when he is making a photo, when he raises his camera and puts it down without shooting, puts it away but next to him, over the table where he is drinking with his friends, or even in his lap, over the knees. Sometimes, Ricardo sees a possible picture but does not take it, he simply stares like he had observed something, noticed something with a certain expression in somebody close. The field of photography is the visual surface of things, but in Ricardo Martín there is an interior pensive aspect, an air of worry in which the camera is sometimes an instrument and other times a talisman, something that is enough to hold with your hands, considering the possibilities that it offers, going forward or not. Nothing creates the impression of being more meditated than his momentary decisions.

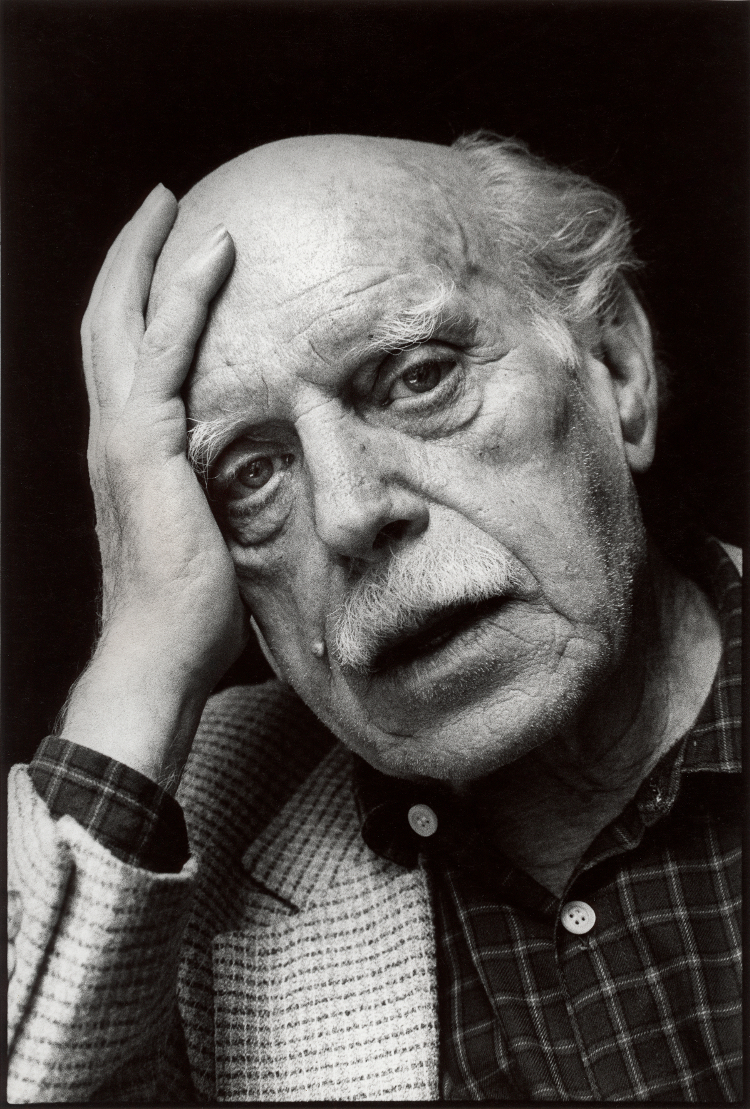

This interior slowness is what unites the portraits that he is shooting throughout the years, more than half of his life, his entire life since he arrived to Madrid and the editorial office of El País in the beginnings of that period, which are his youth and mine and the transition towards democracy and modernity in our country. This period in which even many people that are dead for years were young, much younger that what we remember them and what we noticed back then. Young people do not see their own youth the same way they don’t see that they are growing up. In Ricardo’s portraits there are young people and some memorable elders that preserve the testimony of other times. The elders, who were young in other time of Spanish renovation, old glories to whom nobody paid much attention. Time and calm was needed and there was too much rush. Freedom broke out in politics and in sex. Andy Warhol arrived to Madrid with his platinum wig of synthetic hair, Terenci Moix laughed out loud and Miquel Barceló could be a singer of a pop group. Tierno Galván showed off his ailing lust dancing with a mulata in a Cuban Cabaret, José Bergamín posed in his terrace and not in a history book although death was hovering over him, Julio Caro Baraja removed his glasses of exhausted scholar and Adolfo Suárez smiled like he had all the life and all the politics ahead.

Everyone cared about their stuff, their job, past, obsession, home... They all were in the same time period without knowing it, affected by the same temporary nature, looking to the camera as they were finding some clue to the future. Ricardo went from one to another, with his severe patience, his interested attitude, but not inquisitive. He always kept a certain distance for respecting the other one and his own intimacy. He looked for a while, did not take a picture, moved somewhere else, and then moves with his film roll full - they were other times - and thinks in other picture that could have been made and did not occur in the moment.

It is now when he gathers all these photographies, lays them down in the floor and looks on one after another, chooses and discards them: it is now when he notices that he was portraying the faces of time, the gallery of the faces of a period of time.

Antonio Muñoz Molina

Portrait of a hunter

I have travelled with many photographers in many continents. I have worked with them in interviews, chronicles and reports. Each photographer has his own world in his eyes and does not let the lens until he takes the picture that he aims. One of the best hunters that I have met was Ricardo Martín. Where he sets his sight, he puts the bullet. He is never wrong. This was the exact point of the bullseye where the soul that he wanted to hunt was.

The face is the best external landscape of a person. There are deserts, fertile valleys, mountains and clean and soiled rivers. Ricardo Martín is an incredible explorer of this territory. As years go by, the human face becomes a map with a secret password of the spirit located under the skin. Giving life to a face is the supreme evidence of a photographer. This gift makes him a creator.

The God of the Genesis created the man with a figure of mud and at the end he blew on the forehead and the mud became alive. Any portrait is dead until the artist gives the last brushstroke or the photographer shoots a flash similar to a divine pneuma, which captures life. That final touch of the paint brush or the camera is always an enigma. Maybe it is just an illuminated white spot in the pupils or a blur in the corners of the lips like Leonardo made with la Gioconda or an insignificant grimace in the glabella that is captured by the photographer. Suddenly, slight touch and the enigma is revealed. In fact, life is nothing but a blow that builds our soul and starts to appear in different expressions of the face because they do not only summarise a vital journey but the spirit of time. Only when a photographer is an artist, such as Ricardo Martín, this blow consists in capturing the soul in the moment when it is revealed. It might be just a moment, but eternity is also that instant that is framed in time with the camera.

The human figure was Picasso’s obsession, and barely abandoned it during his long artistic career. The genius knew that there was no best landscape than the body, and this territory, neither deep nor mysterious as the face skin, where all the crossroads and the passions of the story are described.

There is no real testimony, unappealable, cruel sometimes, of the history of the portraits of the characters of a period. All these esthetical movements moved to the detritus of life and at the end lay it over people’s faces with all their dreams, passions and falls in history, like dirt or clear water in a river. Artists like Ricardo Martín confine themselves to record the minutes, such as the diary of a hunter of souls.

Manuel Vicent

Images gallery