A work done by the professors of the Universitat de València Carmel Ferragut and Juan Vicente García Marsilla manifested the economic and urbanistic consequences of the fire in 1447 in Valencia, among them the disappearance of a part of the city’s Islamic design and the subsequent re-ordering. The research connects this devastating episode to a crime committed the days before in a farmhouse of the village of Paiporta and the public execution of the guilty, in a time in which Valencia, the 'Segle d’Or' (the Golden Century), was one of the most populated and dynamic cities of the Western Europe.

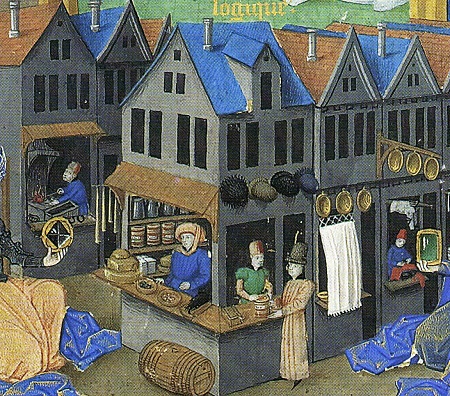

The fire, in one of the most economically active parts of the city and with narrow streets, near to the Islamic wall, became quite large according to the public notaries of the time Berenguer Cardona and Jaume Vinader. The catastrophe caused the destruction of 46 dwellings, all the market stands and the death of ten people, in addition to several injured. Melcior Miralles, priest of the King Alfonso “the Magnanimous” and author of the most famous chronicle of the Valencian 15th century, refers to this fire and to the relationship with the crime, as also does Jaume Roig in his work “Espill” (Mirror).

The fire started around nine o’clock in the night the 16 of March in a carpentry placed near to the Market of the city and lasted seven hours. Other sources say that it was created in the scaffold where the defendant of the Paiporta’s crime were executed.

According to the reports of that time, the crime was perpetrated by the family of a former high officer of the city City Hall of Valencia, Genís Ferrer, who was named councillor of that time the previous year. The fire would had been caused by the Ferrer’s supporters, which burned the scaffold, because of the show caused in the city by the execution. In fact, during the hours of the fire, the churches of Valencia took their saints in procession to calm the divine wrath. During many years, the fire of Valencia and the crime were together in the collective memory.

The work narrating these facts, “The great fire of Medieval Valencia (1447)” has been published in the “Urban History” journal (of the University of Cambridge) and stablishes a parallelism with other fires in other European cities during the modern age, with subsequent large urbanistic reforms (Madrid, León and London, among others). The research also highlights Petro Vetxo, an Italian watchmaker that supervised the rehabilitation of the area after the fire and became one of the authors of the urbanistic reformation.

“This event, shocking for the citizens of the time, has important economic and urbanistic consequences, but even though went unnoticed for the historiography, because sometimes those moments of splendour can cause the forget of the crisis, catastrophes and how our ancestors faced it”, say the experts.

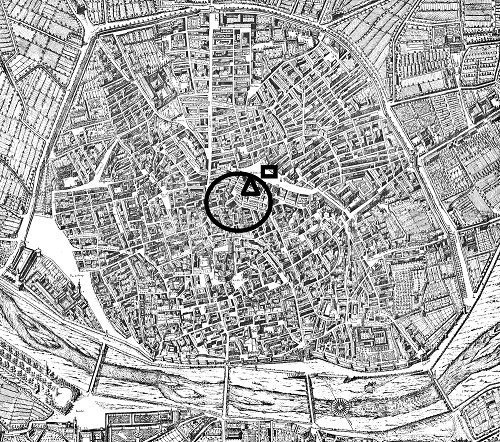

Researchers of the University point out that by analysing the plan of Valencia of the Father Tosca in 1709, two and a half centuries after the disaster, we can find a much more regular design in the part of the urban pattern of the city corresponding to the urbanistic reform promoted by the municipal council of Valencia after the fire.

Petro Vetxo, an Italian watchmaker

With the reconstruction of the damaged part, we can discover the contribution made by characters such as Petro Vetxo, an “engineer”, in the words of Ferragud and García Marsilla, brought to the peninsula by the king Alfonso “the Magnanimous” in order to build a clock for the Royal Palace of Valencia. After that, he continued working for the Crown building weapons, and in other moments, in Russafa and in Montcada, doing ditches or, in 1447, keeping the new clock placed in the “Micalet”, the tower of the Cathedral of Valencia.

According to the experts, there are more individuals like Vetxo than we think, and they are still waiting to be discovered. The research shows the economic effort of the municipal council to indemnify those affected at the sinister (some people lost everything) and to re-establish the market environment, using also old neighbour demands.

Work sources

Carmel Ferragud and Juan Vicente García Marsilla used as sources for this work materials of the Municipal Archive of Valencia (manuals de consells i Sotsobreria de Murs i Valls); of the Archive of the Kingdom of Valencia (Civil Justice); and of the Archive of the Real Colegio del Patriarca or of the Corpus Christi (notarial protocoles).

Carmel Ferragut is a researcher of the López Piñero Institute for the History of Medicine and Science and professor of History of Science and Documentation of the Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry. Juan Vicente García Marsilla is professor of Art History of the Faculty of Geography and History.

Medieval fires in Valencia

In the medieval cities the risk of suffering horrific fires was very high, as well as the difficulties to extinguish them, despite having the extinction services and strategies to face them. Night oil lamps in houses built with high amounts of wood next to other houses were risk factors, in addition to the existence of narrow streets that made the access difficult. Between the strategies against the fire also was the prayers and processions to calm the divine wrath, point out the two researchers of the University.

The city of Valencia at the end of the 15th century had around 40.000 inhabitants inside the walls of the city, and maybe 20.000 in the surroundings. It is important the work “The great fire of medieval Valencia (1447)”, and Valencia was the most populated city of the Iberian Peninsula. The previous years there were fires in the city such as the ones of the years 1405, 1415 and 1423 and also were specially important the ones in the Cathedral in 1469.

Images: