FOR FREE GUIDED TOURS FOR GROUPS ARRANGE WITH voluntariat.cultural@uv.es

REGISTRATION GUIDED TOURS

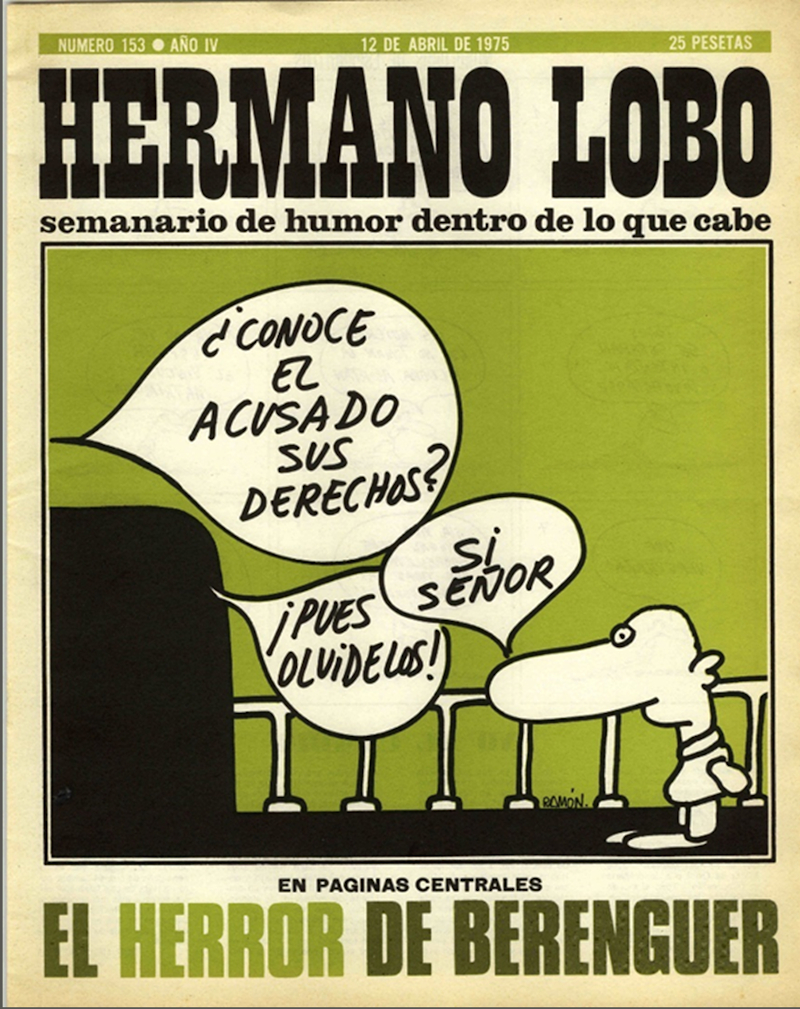

“The time to laugh in a different way had come”, proclaims Manuel Vicent on the frontispiece of this exhibition. To laugh at Franco and his dictatorship without it being a stentorian guffaw, without the watchdogs of the essences with the title of censors feeling tempted to cut it off, with the intelligence of someone who knows the complex and extraordinary language of expressing with drawings what words could not say. In the spring of 1972, a group of intellectuals who, in addition to their opposition to the dictatorship, shared a table and after-dinner conversation at the Picardías restaurant, fertilised the creature: El Huevo Duro (“The Hard-boiled Egg”) —they say they came up with it—, no doubt with the aim of promoting a healthy reflection on the virility of the man who had been the watchman of the West and steersman of the new Spain. Since at that time, the censors believed that to reflect was to kneel before the Almighty, they did not understand the name and the “egg” did not yield results. They had to think of an alternative to baptise the creature with a name that would be more digestible for those registrars of thought. Chumy Chúmez, a thought-anarchist and enthusiast of direct humour, found the solution: to hatch the “egg” so that it would give life to a howling animal, a Hermano Lobo (“Brother Wolf”).

From the publishing house Pléyade, the same one that published the mythical journal Triunfo, on 13th May 1972, the first howl of Hermano Lobo appeared on the street with the subtitle Semanario de humor, dentro de lo que cabe (“Weekly humour magazine, as far as it goes”), a principle that could be summed up in the saying “a word to the wise is enough”. Because, more than words, the journal was full of images as suggestive and provocative as anyone wanted to understand and imagine. From the surrealist drawing of Ops (Andrés Rábago) to the irreverent drawing of Chúmez, the troglodyte of Forges or the absurdity of Gila, among others, they made the magazine much more than a means of laughing at the dictatorship, they turned it into a symbol of rebellion and transgression. That is why it was so successful. The print run of 100,000 copies of that first issue disappeared from the news-stands when the owners had not yet closed for lunch. In successive issues, the print run increased to 150,000 copies, reaching its highest sales figure of 170,000.

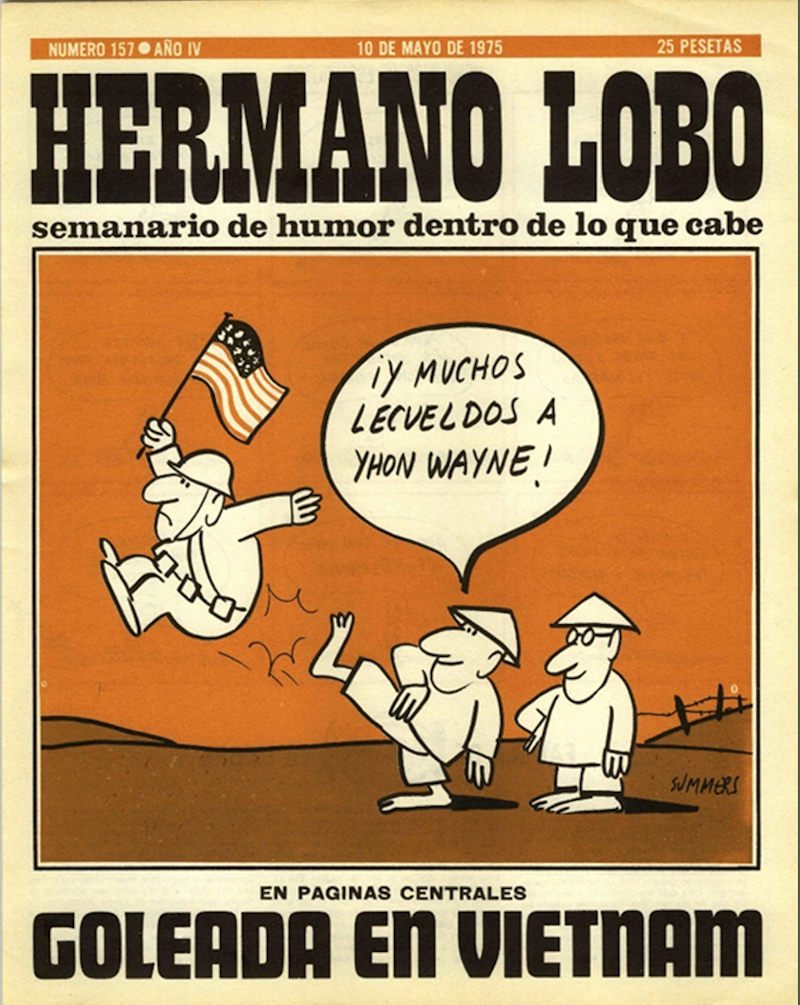

The eyes of many Spaniards soon became accustomed to watching and laughing with Hermano Lobo. Rather than surpassing the decrepit humour of La Codorniz or imitating the irreverent humour of Charly Hebdo, as it has been suggested, Hermano Lobo was in those 70’s the equivalent of that thick glass through which Max Estrella saw the grotesque reality half a century earlier. The regime’s theoretical progressive reforms, from the Fraga law and its theoretical abolition of prior censorship to Arias Navarro’s law on political associations —not parties— were all subjected to the rinse of laughter. The regime’s leading figures, rather than being ridiculed in their “human person”, were mocked in their representative metaverse, in the figure of the fascist wearing a top hat, with a cigar in his mouth and a paunch. The undaunted section of each issue, entitled “7 questions to the wolf”, not only offered answers at a time when to ask was to offend, it also offered hope. It did so with his last and ever-repeated question about when film censorship would disappear, to which the wolf replied: "Next year, God willing

And finally, it seems that God granted it. And on 20st November 1975, the end of the dictator was certified. It is evident that Hermano Lobo did not produce phlebitis in the Caudillo’s body, but it is also unquestionable that his weekly howls were collective invocations to put an end to the dictatorship. A woodworm paper that did not come free of charge. The journal was censured, fined and, finally, seized on two occasions.

Hermano Lobo, despite its format, frequency of publication or language so far removed from the daily press, was a great communicative experience that can hardly be measured in terms of circulation or economic results. It went beyond that, forming part of the street attire of those who wanted to show their discrepancy or their “leftist” status. It was a great meeting point for a plethora of intellectuals and artists of the highest level, such as the aforementioned Manuel Vicent, Francisco Umbral, Manuel Vázquez Montalbán, Luis Carandell, Antonio Burgos, Rosa Montero, Luis Sánchez Polack, José Luis Coll, Eduardo Haro, Fernando Savater, Jesús Pardo… And, of course, where Chumy Chúmez, Gila, El Perich, Forges, Saltés, Quino, Summers, Ops or el Roto, Dodot, Ramón, Elgar, Ortuño… drew and set the standard.

Franco’s death, curiously, together with the increase in competition with publications such as Por Favor, El Papus and the departure of some of the aforementioned cartoonists and writers, caused the decline. The last issue of Hermano Lobo appeared on 5th June 1976, after 213 issues. In its will, the journal declared itself to be secular, republican and bequeathed its moral and spiritual assets to the Platajunta, which at that time brought together most of the democratic and anti-Francoist political organisations.