![]() https://www.facebook.com/MemoriaUniversitat

https://www.facebook.com/MemoriaUniversitat

Catálogo (Online) Catálogo valenciano (pdf) Catálogo castellano (pdf)

VÍDEOS:

23rd April 2011 was the 40th anniversary of the arrest of a group of Valencia University students by Franco’s political police - Brigada Político-Social. The students were imprisoned after 19 days of torture and brutal interrogation at Valencia’s police headquarters. Then, they were found guilty by the Public Order Court, charged with illegal association and propaganda to “prompt Spaniards (…) to fight all violations of human rights, put an end to dictatorship and restore freedom” (Proceedings 593/71, P.O.C.). The prosecution asked for 119 years' imprisonment for such “crimes”. Two years earlier, a group of Valencian female students had gone through a similar experience. Arrested for violating the state of emergency in January 1969, they were sent to prison for not paying the applicable fine, which they deliberately did in order not to sustain the dictatorial regime.

They were not the only Valencia University victims of Franco’s repression policy. Their experience allows us to explore the university's movement against the regime in a period of cultural and social change, and to show such mobilisation and changes by means of individuals and their experiences, which come to describe a whole generation: that of those who actively lived the ending of Franco’s long night.

The exhibition University Students against Dictatorship underlines the importance of the students’ movement in the fight against dictatorship and in the construction of democracy in Spain. It is a memory exercise and a tribute but, above all, a highly topical reflection, as it advocates the application of the values of a generation who thought about a better world.

But, what’s the point in telling the story? Who are the listeners?

The point is to show democracy as a good conquered in the streets, the fruit of collective effort. To appreciate the values, ethics and convictions that prompted a number of citizens to fight dictatorship and to stand up for democracy and the ethical heritage of society as a whole, for the very foundations of the rule of law. To understand the present and to use remembrance as an instrument for the future.

And, above all, the point is to tell the generations born in the democratic period about the imposition of a single discourse, thus facilitating the understanding and assessment of the conflict.

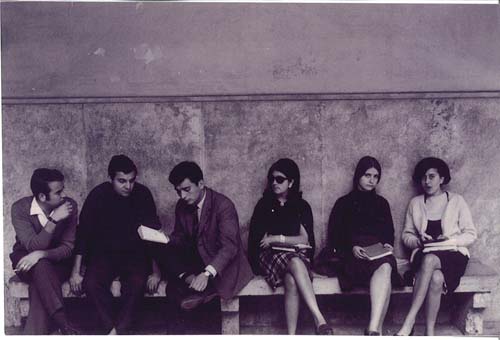

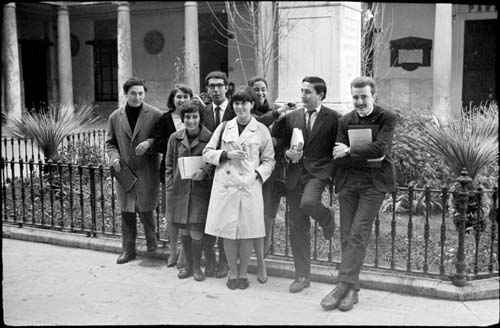

Universitat Literaria de València. 1966. Arxiu Manuel García - Ferran Montesa

The contents of the show are arranged into five exhibition sections, four of them being chronological and one crosscutting.

Section 1. Silence.

1939-1956

Section 1. Silence.

1939-1956

The first section shows visitors Franco’s ideological control over universities between 1939 and 1950, the repression and cleansing of both lecturers and students, the organisation of a minority and classist university working as a militia at the service of the State, and pays special attention to the University of Valencia and events like the execution by firing squad of the University Principal Prof. Peset. The exhibition also shows the control exerted by the SEU, the Francoist union whose tight control –paradoxically- did nothing but arouse the longing for freedom. The indoctrination of students –intended to ensure the sociological continuation of the regime- became more and more important and a growing obstacle as the memory of the civil war faded away as a legitimating factor. This period was characterised by silence, utter control and fear.

Section 2. Awareness.

1957-1964

1957-1964

As of the late 1950s, a number of university initiatives opposed to SEU were put forward. In 1955, 90% of Spanish university students were against the National Movement, according to a survey commissioned by the University Chancellor Laín Entralgo. They were the children of the bourgeoisie, families espoused to Franco’s regime. The fact that university was still a minority institution cannot be overlooked. Startled, the system realized that they were losing contact with the “future of the Nation” and so rushed to resolve the situation with failed projects such as the Asociaciones Profesionales de Estudiantes (APE).

On the one hand, it easily dismantled the first attempts to organise the students’ opposition, with harsh reprisals. On the other, they failed to halt a slow but unstoppable process of political and academic change which would take university to the front line in the fight for freedom and against dictatorship.

Organisation initiatives in Valencia took longer to materialise, if compared to other university districts but by 1957 the first group of the PCE (Spanish Communist Party) had already been set up, the short-lived Agrupación Socialista Universitaria was founded in 1958, and Valencian nationalism started to be organised under the PSV (Socialist Party) in 1964. These are the years of invisibility but also a period of resistance and awareness.

Arxiu Marisa Ros i Ferran Montesa

Section 3. Rebellion.

1965-1975

1965-1975

This is the largest, most important exhibition area, together with the section devoted to the arrests of 23rd April 1971. It deals with the progressive loss of control of university by Franco and the contestation by the classrooms. As was the case in the 1930s, the young became a fundamental mobilisation driver which put apart the regime politically and culturally but also at a vital level. The classrooms became a school for political learning and for the teaching of civic values, irradiating the rest of society.

During this period, the students’ movement deployed contestation measures which wore the regime down. The existence of a deceptive system of representation raised the awareness of students and underlined the inability of the regime to respond to demands which, together with its repressive trend, gave way to bleak prospects. The sordid social and cultural climate finished the job; the break with the Francoist regime was existential. Under the ongoing foreign influence (May 1968 in France, Prague Spring, Vietnam...), this generation fed on and generated an alternative culture of transgression (music, culture, theatre, habits, language...) and, within it, a political culture ultimately leading to fracture. Inspired in modernity, the movement looked ahead.

This exhibition area covers the end of Franco’s era in university. The 1960s were marked by escalating conflict, permanent mobilisation and assemblies, amnesty and freedom campaigns... The university played a pivotal role. The exhibition shows the creation and subsequent disappearance of the Sindicato Democrático de Estudiantes Universitarios (SDEUV), the radicalization of the university movement by 1968 and the mass repression campaign of 1968-1975, the period in which the arrests of 23rd April 1971 took place.

Individual liberties were felt in the air. It was the beginning of the end of the feminine mystique, the onset of sexual liberation and its counterpoint, i.e. clandestine access to contraception and abortion, the first steps of the Feminist Movement were taken. Jeans and long hair became fashionable. No tie, no tight skirts, no short or teased hair. Universities became a stage to the changes.

Everything in the academic scene was questioned: the new educational laws that the government looked to implement, curricula, course contents, master classes, reactionary lecturers… The traditional exercise of authority was rejected. Academics and lecturers changed their positions in line with the contradictions evidenced by a time of crisis.

Autor: Barriopedro. EFE

Section 4. Testimony.

The arrests of 23rd April 1971.

The arrests of 23rd April 1971.

This is the central exhibition area. It invites viewers to approach the subject from oral history. With audiovisual materials and the recreation of a place in memory, the main characters in the arrests of 23rd April 1971 and the fall of women in 1969 reconstruct a common, heterogeneous and complex story told to visitors chorally. The narratives of previous sections are now given a face. Stories and testimonies make room to each other, interrelated in the management of memory.

Section 5. Remembrance.

This section is like a democratic memorial, intended to remember the processes and values that ultimately led to the democratisation of a society as the ethical heritage of society as a whole. Remembrance is conceived as an instrument for the future, as we stand up for values such as justice, freedom, and commitment in order to build a better world.