A study led by researchers in the Group of Radio Astronomy of the University of Valencia has determined the mass of a tiny binary star thanks to its intense radio emissions –rare in such small stars– which compels scientists to review stellar evolution models. The findings of this study have just been published in the latest issue of the journal ‘Astronomy & Astrophysics’.

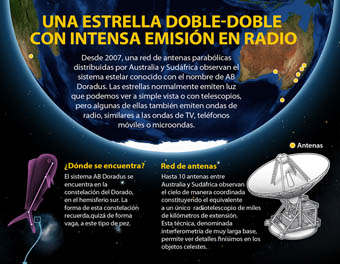

Specifically, this small binary star is known as AB Doradus B and is located in the AB Doradus star system, consisting of two pairs of stars. Stars normally emit light that can be seen with the naked eye or through telescopes, but some also emit radio waves, similar to those from televisions, mobile phones or microwave ovens.

These emissions have made it possible to calculate the mass of the star, which is usually complex, but “when the star is accompanied by another, its orbital motion gives us an accurate way to determine it, as Kepler's laws establish”, says the director of the Astronomical Observatory, José Carlos Guirado, co-author of the study. “The mass of these stars cannot be reproduced by the current models of stellar evolution, so we require a major overhaul of these theories”, adds the scientist in the Department of Astronomy and Astrophysics.

Two stars in one

Since 2007, researchers at the University of Valencia have been observing the AB Doradus star system through the Australian network of radio antennas known as Long Baseline Array (LBA). The LBA consists of a total of 10 antennas located between Australia and South Africa which observe the southern sky in a coordinated manner and are the equivalent to a single radio telescope spanning thousands of kilometres. This technique, which combines the observations from several antennas, is called very-long-baseline interferometry and allows scientists to see very fine details in celestial objects, so much so that if you could take a newspaper to the moon you would be able to read the headlines from the Earth.

The study of the pair Ba and Bb has revealed that these stars, as pointed out by researcher Rebecca Azulay, co-author of the work, “have an intense radio emission that has been captured by the Australian interferometer antennas. But the stars shine at visible wavelengths and not so much at radio wavelengths; then, where do such emissions come from?”, asks the scientist.

“The high speed of rotation of each of the stars makes us suspect that both Ba and Bb are, in turn, the result of two stars in contact at very high rotation rates which merged into a single object. That is why, still today, Ba and Bb revolve on themselves at great speed and produce intense radio waves in the same way that a bicycle dynamo generates light when the wheels turn”, argues Azulay.

In the Large Magellanic Cloud

The AB Doradus star system lies in the constellation of Dorado, a circumpolar constellation visible only from the southern hemisphere and whose form recalls, perhaps vaguely, this type of fish. It is well known because it contains most of the Large Magellanic Cloud, the third closest galaxy to the Milky Way and one of the most attractive extragalactic objects to see with the naked eye.

José Carlos Guirado is the director of the Astronomical Observatory of the University of Valencia and researcher at the Department of Astronomy and Astrophysics. His strands of work include the study of quasars and stellar objects with interferometric techniques and he is participating in the design of future instruments like the Square Kilometre Array (SKA). Rebecca Azulay is a researcher in the Group of Radio Astronomy of the University of Valencia.

‘Dynamical masses of the low-mass stellar binary AB Doradus B’

R. Azulay, J. C. Guirado, J. M. Marcaide, I. Mart-Vidal, E. Ros, D. L. Jauncey, J. F. Lestrade, R. A. Preston, J. E. Reynolds, E. Tognelli and P. Ventura

DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201525704

Last update: 22 de june de 2015 07:00.

News release