The University of Valencia participates in the international study that reconstructs the evolutionary history of human oral bacteria

- Scientific Culture and Innovation Unit

- May 10th, 2021

A new study published in PNAS compares ancient dental calculus of humans, Neanderthals, and other primates. Despite oral microbiome differences, researchers identified ten core bacterial types maintained within the human lineage for over 40 million years. The team, in which the researcher of the University of Valencia Domingo C. Salazar-García participates, discovered a high degree of similarity between Neanderthals and humans, including an apparent Homo-specific acquisition of starch digestion capability in oral streptococci, suggesting that the bacteria adapted to a dietary change that occurred in a common ancestor.

Living in and on our bodies are trillions of microbial cells belonging to thousands of bacterial species - our microbiome. These microbes play key roles in human health, but little is known about their evolution. In a new study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, a multidisciplinary international research team investigates the evolutionary history of the hominid oral microbiome by analysing the fossilized dental plaque of humans and Neanderthals spanning the past 100,000 years and comparing it to those of wild chimpanzees, gorillas, and howler monkeys.

Researchers from 41 institutions in 13 countries, including Cidegent Researcher Domingo C. Salazar-García from the Universitat de València, contributed to the study, making this the largest and most ambitious study of the ancient oral microbiome to date. Their analysis of dental calculus from more than 120 individuals representing key points in primate and human evolution has revealed surprising findings about early human behaviour and novel insights into the evolution of the hominid microbiome.

An enduring microbial community

Working with DNA tens or hundreds of thousands of years old is highly challenging, and like archaeologists reconstructing broken pots, biomolecular archaeoologists also have to painstakingly piece together the broken fragments of ancient genomes in order to reconstruct a complete picture of the past. For this study, researchers had to develop new tools and computational approaches to genetically analyse billions of DNA fragments and identify the long-dead bacterial communities preserved in archaeological dental calculus. Using these new tools, researchers reconstructed the 100,000-year-old oral microbiome of a Neanderthal from Pešturina Cave in Serbia, the oldest oral microbiome successfully reconstructed to date by more than 50,000 years.

“We were able to show that bacterial DNA from the oral microbiome preserves at least twice as long as previously thought”, said James Fellows Yates, lead author from the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History. “The tools and techniques developed in this study open up new opportunities for answering fundamental questions in microbial archaeology, and will allow the broader exploration of the intimate relationship between humans and their microbiome.”

Within the fossilized dental plaque, researchers identified ten groups of bacteria that have been members of the primate oral microbiome for over 40 million years and that are still shared between humans and their closest primate relatives. Many of these bacteria are known to have important beneficial functions in the mouth and may help promote healthy gums and teeth. A surprising number of these bacteria, however, are so understudied that they even lack species names.

Paleolithic interactions and an early love of starch

Although humans share many oral bacteria with other primates, the oral microbiomes of humans and Neanderthals are particularly similar. Nevertheless, there are a few small differences, mostly at the level of bacterial strains. When the researchers took a closer look at these differences, they found that ancient humans living in Ice Age Europe shared some bacterial strains with Neanderthals. Because the oral microbiome is typically acquired in early childhood from caregivers, this sharing may reflect earlier human-Neanderthal pairings and child rearing, as has also been already indicated by the discovery of Neanderthal DNA in ancient and modern human genomes. Researchers found that Neanderthal-like bacterial strains were no longer found in humans after ca. 14,000 years ago, a period during which there was substantial population turnover in Europe at the end of the last Ice Age.

A subgroup of Streptococcus bacteria present in both modern humans and Neanderthals appears to have specially adapted to consume starch early in Homo evolution. This suggests that starchy foods became important in the human diet long before the introduction of farming, and in fact even before the evolution of modern humans. Starchy foods, such as roots, tubers, and seeds, are rich sources of energy, and previous studies have argued that a transition to eating starchy foods may have helped our ancestors to grow the large brains that characterise our species.

“Studies of plant micro remain analysis on Neanderthal dental calculus already point out that Neanderthal diet was more varied than previously thought, and included a variety of plant foods”, says the Valencian researcher Domingo C. Salazar García, one of the senior authors of the study. “However, confirming this thanks to the oral microbiome profile clearly strengthens the idea that our ancestors were not as ‘simple’ as many still portray them, definitely not dietary-wise speaking”, he argues.

Reconstructing what was on the menu for our most ancient ancestors is a difficult challenge, but our oral bacteria may hold important clues for understanding the early dietary shifts that have made us uniquely human. It’s important food for thought - the humble bacterial plaques that grow on our teeth and that we carefully brush away every day hold remarkable clues not only to our health, but also to our evolution.

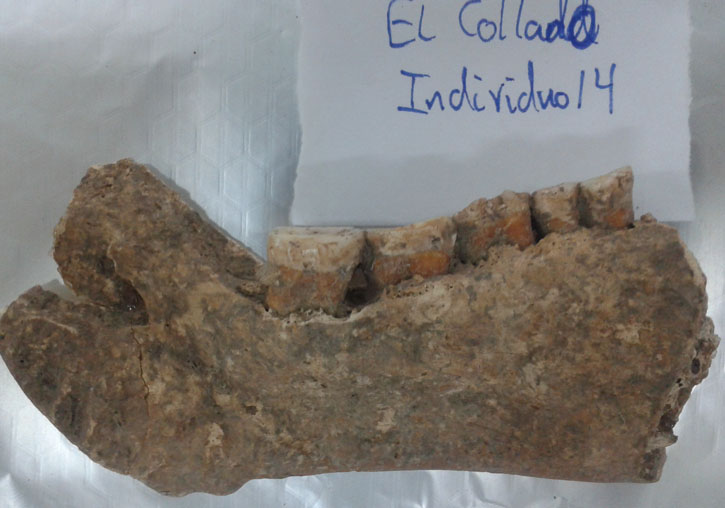

The Iberian archaeological contribution

Many of the archaeological specimens analysed in this study are coming from the Iberian Peninsula as a result of research projects coordinated by the Valencian researcher, who selected and sampled many of them. These include Neanderthal samples from Sima de las Palomas (Murcia), Banyoles (Cataluña), La Güelga (Asturias), Cueva de Valdegoba (Castilla León), and Boquete de Zafarraya (Andalucía). They include as well anatomically modern humans from pre-farming times such as those from the Valencian Mesolithic necropolis of El Collado (Oliva, València). These last, curated at the Museum of Prehistory of València, are of special relevance as they are the most recent pre-farming human samples included in the study.

Furthermore, Valencian dentists and co-authors of the paper Sofía Rodríguez Moroder, Ana Grande Mateo and Elena Escribano Escrivá, collected many of the modern dental calculus used in this study.